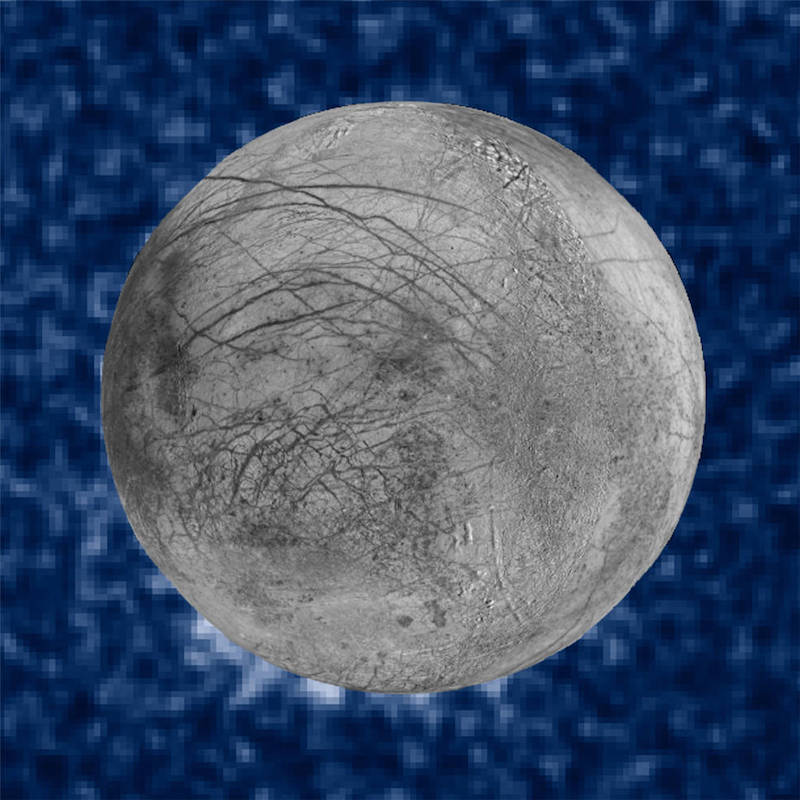

Jupiter’s moon Europa is considered one of the most promising places in our solar system to look for life. We know it has a subsurface ocean not too different from Earth’s. And, like Saturn’s moon Enceladus, it might also have plumes of water vapor, spewing from an underground ocean and erupting from its surface into space. But, unlike the plumes of Enceladus, the water plumes on Europa have been difficult to verify so far. That’s where NASA’s upcoming Europa Clipper mission comes in, NASA said on November 30, 2021. After it launches in 2024, Clipper should be able to confirm Europa’s plume … or not.

But it still might not be easy.

EarthSky 2022 lunar calendars now available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

2 water worlds

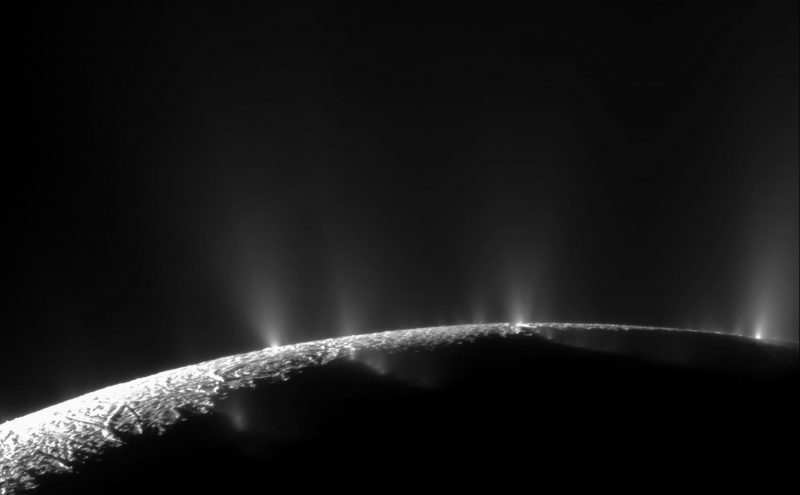

Both Europa and Enceladus have global subsurface water oceans. Trapped under the ice crusts, they are reminiscent of the ocean environment below the ice at Earth’s North Pole. Enceladus does have confirmed water vapor plumes erupting into space, originating from an ocean below. Analysis of the plumes by the Cassini spacecraft – which orbited Saturn, weaving among its moons from 2004 to 2017 – showed that the ocean is quite similar to Earth’s oceans in many ways. Cassini took some spectacular images of them, as seen below.

Europa’s ocean is also thought to be similar to ones on Earth. Evidence shows it is likely habitable by earthly standards. That ocean, however, is believed to be under a thicker ice crust than Enceladus’ and is deeper down. The ocean is currently estimated to be 40 to 100 miles (65 to 160 km) below the surface ice. It’s thought to contain twice as much water as all of Earth’s oceans combined. Like Earth and Enceladus, Europa could also have hydrothermal vents on the floor of its ocean.

What’s exciting is that if there are plumes, then Clipper could sample them, just as Cassini did at Enceladus.

Europa’s water plumes: real or not?

The problem is that scientists still don’t know for sure that the plumes exist. There is growing evidence for them, but the plumes aren’t yet 100% certain. As Lynnae Quick, a member of the Europa Imaging System (EIS) science team stated:

A lot of people think Europa is going to be Enceladus 2.0, with plumes constantly spraying from the surface. But we can’t look at it that way; Europa is a totally different beast.

The detections so far suggest that the plumes are sporadic and faint. This includes observations from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, Hubble Space Telescope and large Earth-based telescopes. Matthew McKay Hedman, a member of Clipper’s Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE) science team at the University of Idaho, said:

We’re still in the space where there’s really intriguing evidence but none of it is a slam dunk.

Why would plumes be significant?

If Europa does indeed have plumes, that would be an exciting discovery. First, simply because seeing plumes of water erupting on other worlds is visually tantalizing. It reminds us of our own planetary home. But also, of course, it’s exciting for science. Such plumes, if connected to the ocean below, could reveal clues as to how habitable the ocean is. Shawn Brooks, now on Clipper’s Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (Europa-UVS) science team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said:

It all comes down to whether Europa is habitable, and that comes down to having some understanding of what is happening below the surface, which we can’t reach yet.

On Enceladus, the plumes are indeed connected to the underground ocean. So essentially, what we see is seawater being sprayed into space from an alien moon.

So what about Europa? If the plumes are confirmed, then Clipper will be ready to sample them just like Cassini did while orbiting Saturn. There is still some debate as to whether Europa’s plumes would originate from the ocean or from smaller lakes of water in the moon’s crust.

The geysers of Enceladus

The Cassini spacecraft was able to fly through some of the geyser-like plumes erupting from Enceladus, and to sample what’s in them. Analysis showed that the plumes of Enceladus contain water vapor, ice crystals, salts and various organic compounds. This gives scientists clues as to what conditions in the ocean itself are like. Cassini even found evidence for active hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor. On Earth, similar environments are oases for a wide variety of ocean life.

Last summer, a team of biologists announced that the data from Cassini revealed the presence of methane in Enceladus’ ocean (perhaps too much of it). According to the researchers, it could be a sign of methanogenic (methane-producing) life in the ocean. On Earth, such activity is associated with methane-producing archaea that live in anaerobic pockets around the globe. But, for Enceladus, it’s still too early to know for sure what we’re looking at, or what the true sources of the methane might be.

Not easy to detect

Meanwhile, Europa’s plumes might be hard to detect, even by a spacecraft like Clipper, which will be traveling to this Jupiter moon. Evidence so far suggests Europa’s plumes are smaller and more sporadic than those on Enceladus. That’s likely because Europa has a stronger gravitational pull than Enceladus; its stronger gravity would keep the plumes closer to the surface. Hedman said:

Even if they’re there, Europa’s plumes might not be that photogenic.

Clipper is well equipped to be able to study Europa, inside and out, regardless of whether it finds plumes or not. Every instrument can gather data on habitable conditions below the surface. As Quick noted:

We don’t have to catch one for a successful mission.

Conducting the search for Europa’s water plumes

Some of the ways that Clipper can look for the plumes include:

The EIS camera suite will search for plumes near Europa’s surface partly by looking for their silhouettes at Europa’s limb (visible edge) when the moon is illuminated by the light of Jupiter. EIS will take images of any plumes found, as well as plume deposits that might be visible on the surface.

The Europa-UVS instrument will try to detect plumes in ultraviolet light, including at the edge of the moon when Europa passes in front of nearby stars. It can also measure the chemical makeup of the plumes.

E-THEMIS (Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System), a thermal camera, will look for hotspots on the surface that may be evidence of active or recent eruptions.

Whether Clipper will succeed in finding the elusive plumes is unknown. Hedman is optimistic, saying:

I do suspect Europa is active and letting some material escape. But I expect that when we actually get to understand how it’s doing that, it’s not going to be what anyone expected.

Clipper will enter orbit around Jupiter in 2030.

Bottom line: Are Europa’s water plumes real? NASA’s Europa Clipper will launch in 2024 to visit this moon of Jupiter to answer this and other questions about its subsurface ocean.