- The dwarf planets Eris and Makemake – which orbit beyond Neptune in our solar system – once were thought to be frozen and geologically dead. But scientists using the Webb space telescope see evidence for heat and active geochemistry inside these little worlds.

- The new result is based on an analysis of frozen methane on the surfaces of Eris and Makemake.

- The evidence suggests unexpected thermal processes inside the dwarf planets.

Scientists once thought the smaller icy worlds in our solar system would be frozen and geologically dead inside. But they’re not. Several icy moons in the outer solar system – and even dwarf planet Pluto – are now known to have heat and liquid water oceans inside. And now we can add the dwarf planets Eris and Makemake to the list. On February 15, 2024, researchers at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Texas, using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), said they’ve found evidence for heat and active geochemistry within both, based on analysis of frozen methane on the dwarf planets’ surfaces.

The research team published its peer-reviewed findings in the journal Icarus on February 8, 2024. A preprint version of the paper is also available on arXiv.

Eris is about the same size as Pluto, but three times as far from the sun, in the Kuiper Belt. It has one tiny known moon called Dysnomia. Makemake, also in the Kuiper Belt, is just slightly smaller than Pluto. It also has a tiny moon, temporarily called S/2015 (136472) 1 (or MK 2).

Geothermal activity inside Eris and Makemake

Both Eris and Makemake are small, icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of Neptune. Both have frozen methane on their surfaces. Scientists expected that the methane would be similar to that found in comets. They were expecting primordial methane, left over from the formation of the early solar system billions of years ago. But that’s not what Webb found. Lead author Christopher Glein at the Southwest Research Institute stated:

We see some interesting signs of hot times in cool places. I came into this project thinking that large Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) should have ancient surfaces populated by materials inherited from the primordial solar nebula, as their cold surfaces can preserve volatiles like methane. Instead, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) gave us a surprise! We found evidence pointing to thermal processes producing methane from within Eris and Makemake.

Determining if methane is primordial or not

To determine the type of methane, the researchers measured the deuterium (heavy hydrogen, D) to hydrogen (H) ratio. That ratio can tell scientists whether the methane is primordial or more recently produced by geochemical processes. It could even provide clues as to whether there might be liquid water inside Eris and Makemake. As Glein explained:

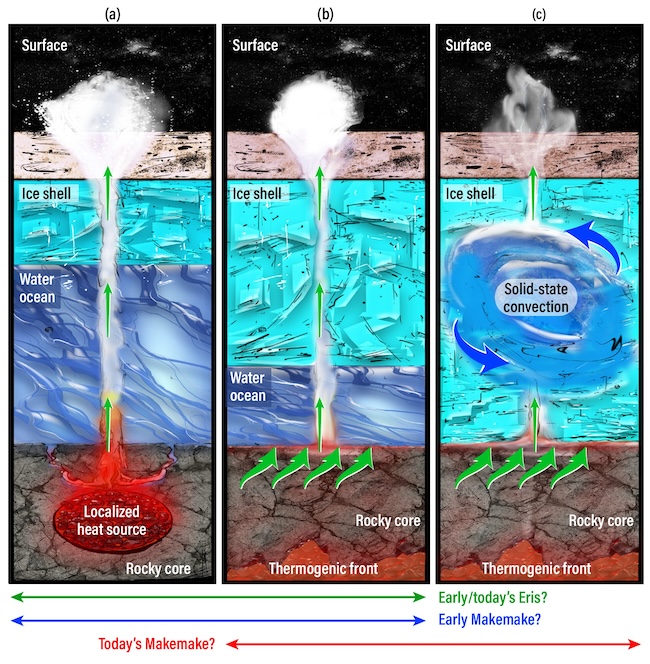

The moderate D/H ratio we observed with JWST belies the presence of primordial methane on an ancient surface. Primordial methane would have a much higher D/H ratio. Instead, the D/H ratio points to geochemical origins for methane produced in the deep interior. The D/H ratio is like a window. We can use it in a sense to peer into the subsurface. Our data suggest elevated temperatures in the rocky cores of these worlds so that methane can be cooked up. Molecular nitrogen (N2) could be produced as well, and we see it on Eris. Hot cores could also point to potential sources of liquid water beneath their icy surfaces.

Interestingly, the paper also noted that the methane on Saturn’s moon Titan is likely not primordial, either:

We also suggest that lower-than-expected D/H and 84Kr/CH4 ratios in Titan’s atmosphere disfavor a primordial origin of methane there as well.

Icy worlds more active than previously thought

Scientists had previously assumed that small icy bodies like Eris and Makemake, or even moons like Enceladus and Europa, would be geologically dead inside, at least for the most part. In the case of Saturn’s Enceladus and Jupiter’s Europa, we now know the gravitational push-and-pull from their parent giant planets can help keep them warm inside … even hot. Geochemical processes can also help maintain that heat. This seems to be what’s happening in Eris and Makemake. Even if not occurring right now, the evidence still suggests these processes were geologically recent. Co-author Will Grundy at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, said:

If Eris and Makemake hosted, or perhaps could still host warm, or even hot, geochemistry in their rocky cores, cryovolcanic processes could then deliver methane to the surfaces of these planets, perhaps in geologically recent times. We found a carbon isotope ratio (13C/12C) that suggests relatively recent resurfacing.

Could Eris and Makemake be habitable?

It’s a surprising but exciting discovery that these small icy worlds can still have warm hearts on the inside. Could they be habitable, at least for microorganisms? We don’t know yet, but it no longer seems inconceivable. Even way out in the Kuiper Belt. Additional observations and future missions to some of them will help scientists determine whether life is actually possible in some of the most unexpected of places. As Glein noted:

After the New Horizons flyby of the Pluto system, and with this discovery, the Kuiper Belt is turning out to be much more alive in terms of hosting dynamic worlds than we would have imagined. It’s not too early to start thinking about sending a spacecraft to fly by another one of these bodies to place the JWST data into a geologic context. I believe that we will be stunned by the wonders that await!

As for the methane possibly being biological in origin, the researchers did not examine this specific theory in detail. The paper said:

We do not pursue investigation of biologically produced methane because non-biological processes can explain the data, and life is the hypothesis of last resort.

Bottom line: NASA’s Webb space telescope shows that icy dwarf planets Eris and Makemake have been warm and geologically active on the inside recently, and may still be.

Via Southwest Research Institute