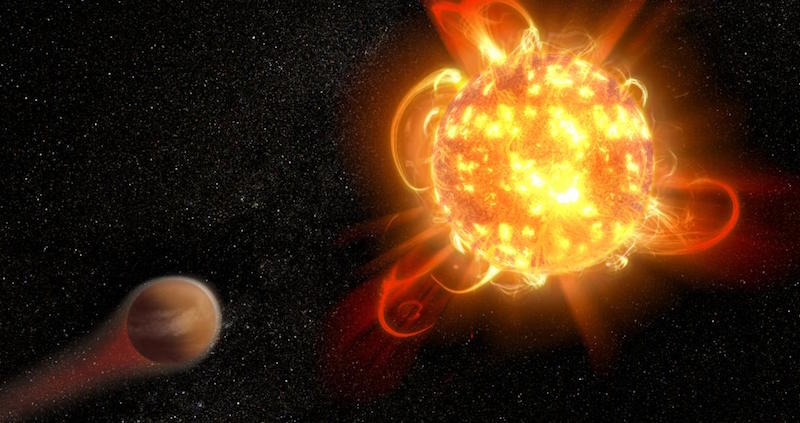

In recent years, astronomers probing the edges of the Milky Way have observed very strong explosions on stars, which they’ve dubbed “superflares,” that have energies up to 10,000 times that of typical solar flares.

Superflares happen when stars – for reasons that scientists still don’t understand- eject huge bursts of energy that can be seen from hundreds of light years away. Until recently, researchers assumed that such explosions occurred mostly on stars that, unlike Earth’s sun, were young and active.

Now, new research suggests superflares can also occur on older, quieter stars like our own sun, albeit more rarely, perhaps once every few thousand years.

University of Colorado researcher Yuta Notsu is the lead author of the peer-reviewed study, published May 3, 2019, in The Astrophysical Journal. Notsu said the study results should be a wake-up call for life on our planet. That’s because if a superflare erupted from the sun, he said, Earth would likely sit in the path of a wave of high-energy radiation. Such a blast could disrupt electronics across the globe, causing widespread blackouts and shorting out communication satellites in orbit. Notsu said in a statement:

Our study shows that superflares are rare events. But there is some possibility that we could experience such an event in the next 100 years or so.

Scientists first discovered superflares via NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. The spacecraft, which looks for exoplanets circling distant stars, also found something odd about those stars themselves. In rare events, the light from distant stars seemed to get suddenly, and momentarily, brighter.

Notsu explained that normal-sized flares are common on the sun. But what the Kepler data was showing seemed to be much bigger, on the order of hundreds to thousands of times more powerful than the largest flare ever recorded with modern instruments on Earth. And, Notsu said, that data raised an obvious question: Could a superflare also occur on our own sun? Notsu said:

When our sun was young, it was very active because it rotated very fast and probably generated more powerful flares. But we didn’t know if such large flares occur on the modern sun with very low frequency.

To find out, Notsu and an international team of researchers turned to data on superflares from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft and from the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. Based on the team’s calculations, younger stars tend to produce the most superflares. But older stars like our sun, at 4.6 billion years old, aren’t off the hook. Notsu said:

Young stars have superflares once every week or so. For the sun, it’s once every few thousand years on average.

Notsu can’t be sure when the next big solar light show is due to hit Earth. But he said that it’s a matter of when, not if. Still, that could give humans time to prepare, protecting electronics on the ground and in orbit from radiation in space. He said:

If a superflare occurred 1,000 years ago, it was probably no big problem. People may have seen a large aurora. Now, it’s a much bigger problem because of our electronics.

Bottom line: New research suggests a superflare could happen on our sun.