Tardigrades – also known as water bears – are some of the toughest and most resilient creatures on Earth, even though they are virtually microscopic in size, less than a millimeter long. They’re known to be able to survive almost any environment you can throw them into, even space. Now, it seems that some of them (or possibly their remains) are calling the moon home, thanks to a crash landing of a spacecraft a few months ago. But while tardigrades might be hardy, there’s no reason to think they’ll be taking over our nearest celestial neighbor, any time soon.

The tardigrades were part of a “lunar library” sent to the moon on Israel’s Beresheet spacecraft. That library was a project of the Arch Mission Foundation, a nonprofit organization whose goal is to create “a backup of planet Earth.” The library, the size of a DVD, included 30 million pages of information, human DNA samples and thousands of dehydrated tardigrades.

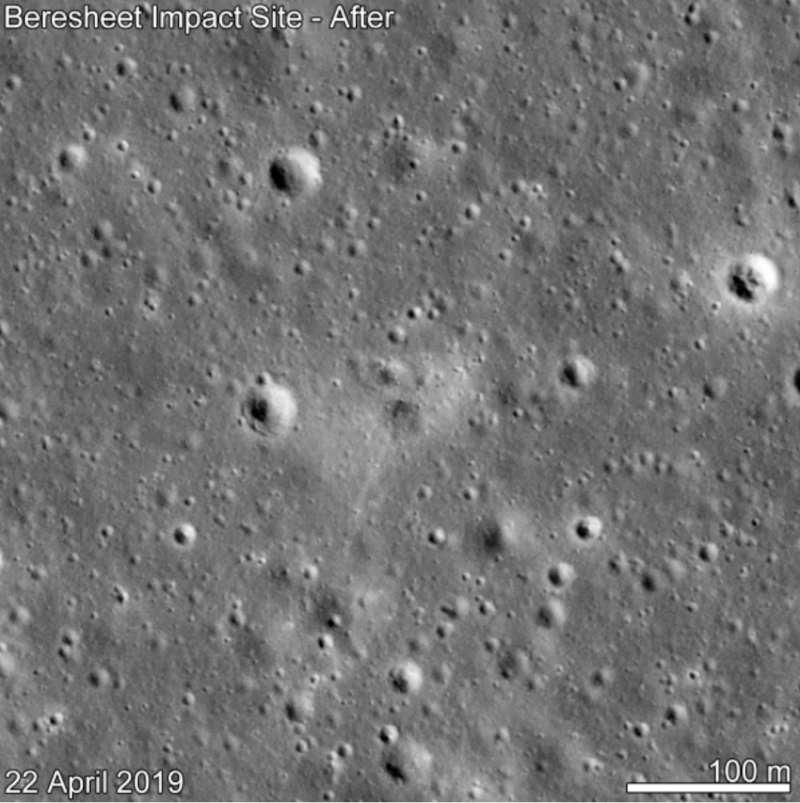

Beresheet attempted its landing in the Sea of Serenity on April 11, 2019, but crashed after a problem with the engine in the last moments. As Nova Spivack, founder of AMF, recounted:

For the first 24 hours we were just in shock. We sort of expected that it would be successful. We knew there were risks but we didn’t think the risks were that significant.

Since Beresheet had crashed, Spivack and others needed to know the fate of the library. Did it survive the crash? What about the tardigrades? Were they strewn across the lunar surface when the crash occurred? Since the library was designed to last millions of years, and considering its composition – made of thin sheets of nickel – and the trajectory of the spacecraft in the final moments, Spivack thinks it likely did remain mostly intact.

In all likelihood then, the tardigrades in the library are still sitting there in their dehydrated dormant state as they were, waiting to be revived again. They can’t do that on their own, though; they need to be brought back to Earth so they can be exposed to an atmosphere again. Only then can they be rehydrated, so there is little worry about them taking over and colonizing the moon!

The idea was to see how well the tardigrades survived the trip to the moon and whether they could be revived again later. Tardigrades are known for entering dormant states in which all metabolic processes stop and the water in their cells is replaced by a protein that turns the cells into glass. This is completely normal for them. Tardigrades have been revived as much as 10 years after becoming dormant, although scientists think they could probably survive much longer without water.

Spivack hadn’t originally planned to send any DNA to the moon this soon, tardigrades or otherwise, but then changed his mind a few weeks before the library was sent to the Israelis. As well as the dehydrated tardigrades, other samples were included in the epoxy resin between each layer of nickel. These included hair follicles and blood from Spivack himself and 24 other people. Even some samples from holy sites were included, such as the Bodhi tree in India.

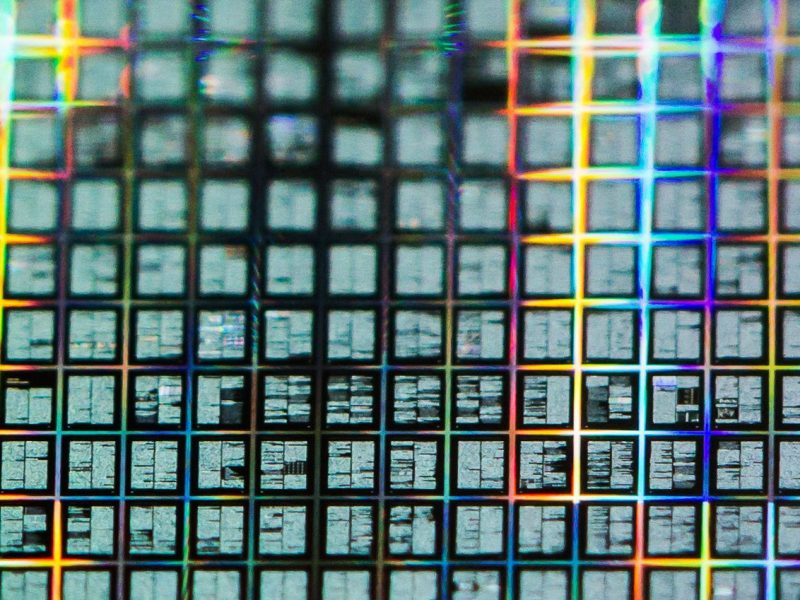

The library also contains delicate engravings in the nickel, which were done by scientist Bruce Ha, who had developed a technique for engraving high-resolution, nano-scale images into nickel. Images were etched into glass using lasers and then nickel is deposited in a layer on top, atom by atom. The images look holographic – three-dimensional – and are so small you need a microscope with 1,000x magnification to see them.

There was some concern that the resin might damage the nickel engravings but Spivack said it may actually have helped saved the library from destruction on impact:

Ironically, our payload may be the only surviving thing from that mission.

There are 25 layers of nickel in the library, each one only a few microns thick (one micron is one thousandth of a millimeter). Those layers contain a wide range of earthly goodies: 60,000 high-resolution images of book pages, include language primers, textbooks, and keys to decoding the other 21 layers. This includes nearly all of the English Wikipedia, thousands of classic books, and even the secrets to David Copperfield’s magic tricks. All of that is found in only the first four layers. Other layers contain the DNA samples and tardigrades.

Spivack wants to send more similar libraries to the moon and beyond in the future, including DNA samples. The idea is too have multiple “backups” of life on our planet, including from endangered species. It’s an elegant solution, since thousands of copies of the library can easily be made, and terabytes of data can be kept in a small vial of liquid. A new AMF crowdfunding campaign this fall will solicit DNA samples from volunteers to include on the next moon mission. It would seem prudent to have backup copies of life on this planet, as Spivack explained:

Our job, as the hard backup of this planet, is to make sure that we protect our heritage, both our knowledge and our biology. We have to sort of plan for the worst.

Bottom line: Some of the hardiest organisms known on Earth, tardigrades, were aboard the Beresheet spacecraft that crashed on the moon last April. But with no atmosphere or water, there’s practically no chance they could revive themselves out of their dormant dehydrative state.