Recent genetic studies on the Uros people in the Andes mountains of Bolivia and Peru – the longest continental mountain range in the world – suggest they may be descendants of the first settlers that arrived at the Lake Titicaca watershed some 3,700 years ago. These findings may put to rest disagreements among anthropologists about the origins of this central Andean ethnic group. The Uros people have been the subject of much study in part due to this disagreement, and also because of their complex history and unique way of life. The new results are based on genetic research by scientists associated with National Geographic’s Genographic Project. These scientists published the new results September 11, 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE.

In this study, there is also unexpected evidence of some distinct genetic differences between the Uros populations in Peru and Bolivia.

In a September 11 press release, Spencer Wells, the Genographic Project director and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence, commented:

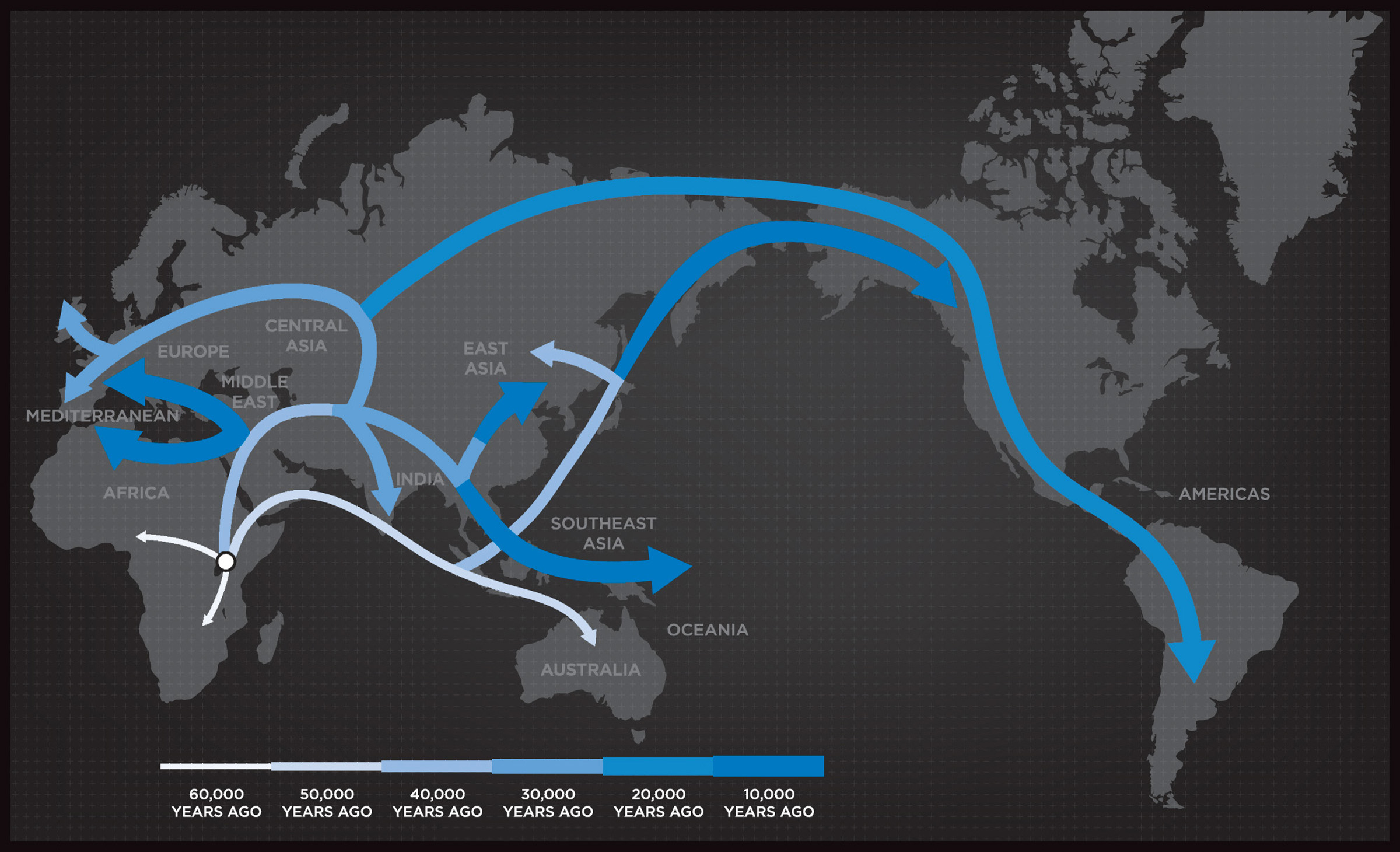

The timing of human settlement in the Andean Altiplano is one of the great mysteries of our species’ worldwide odyssey — a vast, high-altitude plain that seems utterly inhospitable, yet it has apparently nurtured a complex culture for millennia. This significant new study reflects the importance of the Genographic team’s careful, patient work with the members of the indigenous communities living in this remote corner of the mountainous South American terrain, and sheds light on how our species has adapted to disparate ecosystems since its relatively recent exodus from an African homeland less than 70,000 years ago.

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in Bolivia and Peru during the 16th century, they encountered several indigenous cultures in the Altiplano region, the central Andes mountains of South America. Among them were a minority ethnic group, the Uros, that had a history of discrimination by pre-Inca, Inca, and Spanish occupiers of that region. Their native language, Uruquilla, was forever lost during Spanish rule.

As a result of invasions over much of their history, many Uros, displaced from their land, forged a living on the water, building large floating islands on which they built homes, even villages, using reeds from along the lakeshore as construction materials. The Uros depended heavily on the aquatic systems of Lake Titicaca and other area rivers and lakes for their livelihood, hunting birds, collecting eggs, and fishing.

Today, there are about 2,000 Uros in Peru, many that live on floating islands made of reeds on Lake Titicaca. In Bolivia, about 2,600 Uros live by lakes and rivers. The history and way of life of the Uros peope, known as Qhas Qut suñi which means “people of the lake” in the ancient Uruquilla language, have attracted visitors fascinated by them, giving rise to tourism and reed crafts industries in the Altiplano.

The research team was led by Professor José Raul Sandoval of Universidad San Martin de Porres, in Lima, Peru. He is a Peruvian who was born by the shores of Lake Titicaca. The team obtained DNA samples from 388 individuals belonging to four major ethnic groups in the Altiplano, including the Uros people. They identified genetic markers in specific parts of the DNA; these are random mutations that occur per several generations, acting as milestones in an evolutionary path. Every population carries specific genetic markers that differentiate it from others. It is this technique of using genetic markers to identify populations that has enabled scientists to create an intricate genetic tree of myriad branches representing human populations around the word, all originating from the common ancestors of us all that lived in Africa about 70,000 years ago.

Even though modern-day Uros people share common lineages with other ethnic populations in the Altiplano, the researchers were able to trace genetic markers in their DNA, backtracking through twigs in the human evolutionary genetic tree to a common branch representing ancestors that likely first migrated to the Altiplano, or central Andean mountains, about 3,700 years ago. In another unexpected finding, the scientists found that the Peruvian and Bolivian Uros people were genetically distinct. At some point in the past, a branch representing the Uros people had split in two, creating two distinct populations.

Bottom Line: A team of scientists associated with the National Geographic’s Genographic Project have found compelling genetic evidence that the Uros people of Bolivia and Peru have a distinct ancestry that may date back as far as 3,700 years ago to the first settlers in the central Andean mountains region known as the Altiplano. Researchers were also surprised to find that there are distinct genetic differences between Uros populations in Bolivia and Peru.