Robert Perkins originally wrote this article for Caltech on February 13, 2023. Read the original article here. Edits by EarthSky.

Leonardo da Vinci and gravity

Engineers from Caltech have discovered that Leonardo da Vinci’s understanding of gravity – though not wholly accurate – was centuries ahead of his time.

The journal Leonardo published an article in which the researchers draw upon a fresh look at one of da Vinci’s notebooks. They show that the famed polymath had devised experiments to demonstrate that gravity is a form of acceleration. Furthermore, he modeled the gravitational constant – denoted by the capital letter G in later theories of gravity by Newton and Einstein – to around 97% accuracy.

Da Vinci, who lived from 1452 to 1519, was well ahead of the curve in exploring these concepts. It wasn’t until 1604 that Galileo Galilei would theorize that the distance covered by a falling object was proportional to the square of time elapsed.

Then it wasn’t until the late 17th century that Sir Isaac Newton would expand on Galileo’s theory to develop a law of universal gravitation. Da Vinci’s primary hurdle was that he was limited by the tools at his disposal. For example, he lacked a means of precisely measuring time as objects fell.

Last chance to get a moon phase calendar! Only a few left. On sale now.

Discovering gravity in Da Vinci’s work

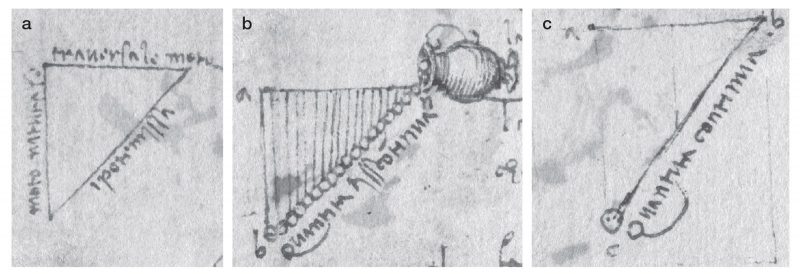

Mory Gharib, the Hans W. Liepmann Professor of Aeronautics and Medical Engineering, first spotted Da Vinci’s experiments. Gharib was looking in the Codex Arundel, a collection of papers written by da Vinci that cover science, art and personal topics. In early 2017, Gharib was exploring da Vinci’s techniques of flow visualization to discuss with graduate students, when he noticed a series of sketches. These sketches showed triangles generated by sand-like particles pouring out from a jar in the newly released Codex Arundel, which the public can view online courtesy of the British Library. Gharib said:

What caught my eye was when he wrote Equatione di Moti on the hypotenuse of one of his sketched triangles, the one that was an isosceles right triangle. I became interested to see what Leonardo meant by that phrase.

To analyze the notes, Gharib worked with colleagues Chris Roh and Flavio Noca. At the time, Roh was a postdoctoral researcher at Caltech and is now an assistant professor at Cornell University. Noca is at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland in Geneva. Noca provided translations of da Vinci’s Italian notes (written in his famous left-handed mirror writing that reads from right to left) as the trio pored over the manuscript’s diagrams.

Leonardo da Vinci experiments with gravity

In the papers, da Vinci describes an experiment in which a water pitcher moves along a straight path parallel to the ground, dumping out either water or a granular material (most likely sand) along the way. His notes make it clear that he was aware that the water or sand would not fall at a constant velocity but rather would accelerate. Also, he showed that the material stops accelerating horizontally, as the pitcher no longer influences it, and that its acceleration is purely downward due to gravity.

If the pitcher moves at a constant speed, the line created by falling material is vertical, so no triangle forms. If the pitcher accelerates at a constant rate, the line created by the collection of falling material makes a straight but slanted line, which then forms a triangle. And, as da Vinci pointed out in a key diagram, if the pitcher’s motion is accelerated at the same rate that gravity accelerates the falling material, it creates an isosceles right triangle. This is what Gharib originally noticed when da Vinci had noted Equatione di Moti, or equalization (equivalence) of motions.

Close but not perfect

Da Vinci sought to mathematically describe that acceleration. It is here, according to the study’s authors, that he didn’t quite hit the mark. To explore da Vinci’s process, the team used computer modeling to run his water vase experiment. Doing so yielded da Vinci’s error. Roh said:

What we saw is that Leonardo wrestled with this, but he modeled it as the falling object’s distance was proportional to 2 to the t power [with t representing time] instead proportional to t squared. It’s wrong, but we later found out that he used this sort of wrong equation in the correct way.

In his notes, da Vinci illustrated an object falling for up to four intervals of time. It’s a period through which graphs of both types of equations line up closely. Gharib said:

We don’t know if da Vinci did further experiments or probed this question more deeply. But the fact that he was grappling with this problem in this way – in the early 1500s – demonstrates just how far ahead his thinking was.

Bottom line: A new look at the notes of Leonardo da Vinci show that he studied and understood much about gravity centuries ahead of his time.

Source: Leonardo da Vinci’s Visualization of Gravity as a Form of Acceleration