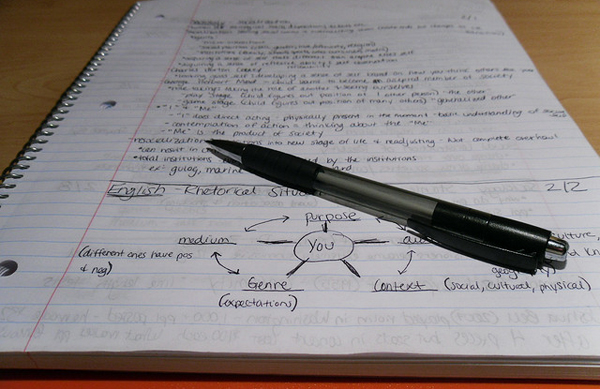

I’m composing this post using a laptop, and with good reason. Typing on a computer keyboard is one of the finest luxuries of modernity. It’s fast and efficient and conveniently equipped with with spellcheck. Typing is like gliding on ice, hand-writing like wading through a swamp. And computers aren’t just for offices anymore. As laptops become increasingly ubiquitous, they’re showing up in classrooms too, replacing more humble spiral bound notebooks and ballpoint pens as many students’ note-taking tools of choice. Not everyone is thrilled about this. There are plenty of reasons why laptop note taking may not optimize learning – Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, to name but a few. But online distractions aren’t the only problem. According to a new study published in Psychological Science, the note taking style adopted by laptop users could itself hinder academic performance.

The potential benefits of note taking are twofold. First, and most obviously, they record class content so that it can be reviewed later on, a concept referred to as “external storage.” The second perk is something called “encoding.” The idea is that the act of processing and paraphrasing material from a lecture into one’s own words improves the chances of the information being understood and retained. If encoding is important, then typing notes – which most people can do much faster than writing – might result in a kind of mindless dictation, rapidly tapping out words in real time without fully comprehending them.

To examine the possible advantages of longhand note taking, researchers from Princeton and UCLA subjected students to several TED Talks and then – after a break featuring “distractor tasks” designed to disrupt memory – quizzed them on their recall of the content. Students were equipped with either (internet-free) laptops or paper notebooks while they watched the talks and instructed to take notes as they normally would for a class. Test questions included both factual recall (names, dates, etc.) or conceptual applications of the information.

Because the quantity and quality of notes have been previously shown to impact academic performance, students’ notes were also analyzed for both word count, and the degree to which they contained verbatim language from the talks. In general, students who take more notes fare better than those who fewer notes, but when those notes contain more verbatim overlap (the mindless dictation issue) performance suffers. As one might expects, students who watched the TED Talks equipped with laptop were able to take down more notes, since typing kicks hand-writing’s butt in terms of speed. However, the luxury of quick recording also resulted in the typed notes having significantly more verbatim overlap than the written ones, and this was reflected in test scores. While, laptop and longhand note takers both fared similarly on factual questions, those taking the tedious pen-and-paper notes had a definite edge on the conceptual questions. So while laptops allowed students to generate more notes (on average a good thing), their tendency to encourage writing down information word-for-word appeared to hinder the processing of information.

Fine, you’re thinking, now that I know that, I can continue to use my laptop as long as I make an effort to paraphrase rather than just typing everything out verbatim. That way I can keep the high word count, but lose the mindless dictation factor. The best of both worlds. Well good luck to you, because the researchers tried that and apparently old habits die hard. In a similar study, they again outfitted one group of students with notebooks and another with laptops. But this time a third group was added: students who received both laptops and sage advice like, “Take notes in your own words and don’t just write down word-for-word what the speaker is saying.”

It didn’t help. At least not in terms of note quality. Simply telling students to paraphrase instead dictate on the laptops did little to discourage verbatim overlap, which remained higher in both laptops groups than in the longhand group. The results in test performance were less obvious. While the longhand group outperformed the laptop-only group (those not given special instructions) in answering questions, the laptop group instructed to take less verbatim notes fell somewhere in between. The difference was not statistically significant, but it hints at the possibility that there may be some other factor of note taking, besides just verbatim overlap and word count, affecting learning.

So far things aren’t looking great for laptop note takers. However, neither of the experiments discussed thus far allowed students to review their notes. They focused exclusively on the encoding benefit while ignoring external storage. Yet outside the lab, it’s not unheard of for students to use their notes to study prior to an exam. If students had opportunity to look at their notes before being tested on the material, might the laptop notes – with their higher word count – finally provide some advantage over the longhand notes? It seems plausible enough, right? In a third study, students who’d taken notes via laptop or pen-and-paper returned to the lab a week later (presumably after numerous real life distractor tasks) at which time some of them were reunited with their notes for some pre-exam studying, while others just went straight to the test questions.

And the winner is? Well this is awkward, it’s longhand note takers yet again. Though this time it was specifically longhand note takers allowed to study their notes. While it’s not so surprising that studying improved test performance (both laptop and longhand note takers who didn’t get to review their notes did equally poorly), it is interesting that students studying from laptop notes did noticeably worse than those studying from longhand notes. Could longhand notes, despite providing less volume to study from, actually be superior in terms of external storage as well as encoding? Maybe, though the authors point out another possible explanation: it could also just be that information was better encoded in the initial taking of longhand notes, so that reviewing them more easily jogged memories pushed back by a week of forgetting. Unfortunately the study didn’t go the extra step of asking students who hadn’t viewed the lectures to study from other’s longhand or laptop notes (something that happens often enough in real academic settings). Maybe next time.

Overall, like many psychological studies, this one could have benefited from a larger number of subjects (67, 151, and 109 students, respectively, participated in the three portions). The authors themselves mention that some effects may have been too subtle to see due to the smallish sample size. We certainly don’t have, from this single study, the definitive recipe for scholastic success. Which is just as well, since any such epiphany would be too late for the current semester. So for those of you on a collision course with final exams, just study whatever notes you have and get some sleep. Whatever the outcome, at least it’ll be over soon.