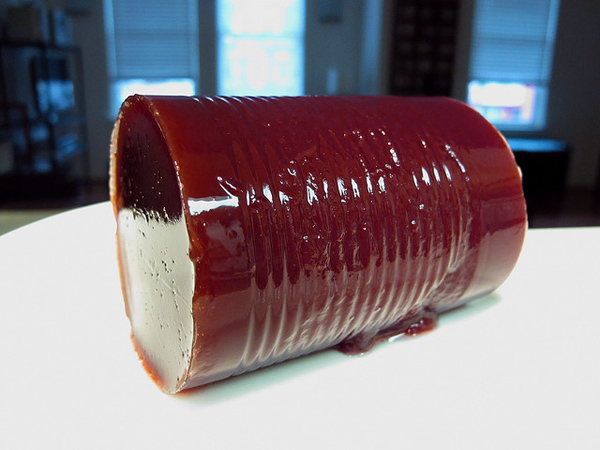

My first encounters with cranberries were in the form of cranberry sauce, specifically the canned variety. The product, a homogenous, sweetened gel, bore little resemblance to fruit. It emerged from its container like a bundt cake from a mold, a perfect can-shaped lump, still bearing ringed indents from the metal. To my childish palette, it was the best thing ever, and for years attempts to persuade me to eat homemade cranberry sauce with actual chunks of real cranberries were met with sour moods and bitter disapproval.

As an adult, I learned to appreciate more authentic and even creative versions of the classic holiday condiment. Novel cranberry sauces with ingredients like walnuts and jalapeños are now welcome on my plate. Cranberries too have broadened their horizons over the years. From their simple beginnings in sauces and “juice cocktail”, they’ve branched out into dried snacks, muffin and cookie ingredients, and nutritional supplement pills. Not bad for a fruit that is, by many standards, inedibly sour in its raw form. Though a reputation for providing health benefits also helped, the cranberry owes much of its success to some basic biological quirks that make it ideal for cultivation.

Better off bitter

The American cranberry is an evergreen shrub native to the eastern part of North America. While the common cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccos) has a broader distribution, including northern Europe and Asia, it is not as heavily cultivated as the new world version of the fruit.

A relative of the blueberry, cranberries differ from this sweeter cousin in habitat. The American cranberry grows in bogs with acidic soil. Cranberries don’t actually grow underwater, just near it. However, growing in wet environments made it possible for them to use the water as a means of seed dispersal. Air pockets inside the berries allow them to float.* Since they don’t rely on animals to disperse their seeds (and prefer to grow close to water), cranberries need to avoid being too delicious. Tannins lend the fruit its tartness. These are the same chemicals that give unripe bananas that awful mouth-drying effect.† Having rendered themselves unappetizing to most critters, cranberries are left alone until they fall from their vines and are ferried to new locations by water.

Bobbing for berries

Its ability to float would eventually also make the cranberry a popular fruit for cultivation. In the early days of cranberry farming, the crop was “dry harvested” – that is, the berries were hand-picked from the shrubs, which was slow and labor intensive. But in the mid 20th century someone realized that it would be easier to flood the bogs in which cranberries were grown, rattle the branches a bit, and then skim the buoyant berries from the top of the water. This “wet harvesting” technique is now used for the bulk of cranberry farming. Most farmed cranberries make their way into juices and other processed products. Some are still sold fresh, and these are typically dry-harvested to assure that they’re fresher and not too battered.

A Thanksgiving tradition

Somewhere during the month of November, U.S. schoolchildren receive a (greatly simplified) history lesson on the holiday for which they are about to get two full days of reprieve from education. As the story goes, the nation’s settlers, having (barely) survived a brutal first winter and successfully harvested enough food to perhaps live through a second one, sat down to a celebratory feast with Native Americans (whose farming know-how helped to make said harvesting possible in the first). And thus American Thanksgiving was born. ‡

Well, the funny thing about that “first” Thanksgiving – other than the fact that harvest festivals had long been common fare in Europe, and that Plymouth pilgrims weren’t exactly the first Europeans to make their way to the new world – is that we don’t have the recipe cards from the event. What was served at the 1621 celebration is largely speculation. We know that they had deer, courtesy of the Wampanoag tribe. Pies were probably not on the menu as the settlers’ sugar stash was pretty low by that point. And there is no record of mashed potatoes and gravy, marshmallow yams, or cranberry sauce. Since Native Americans regularly used cranberries for food and dye and such, it’s possible the sour fruit made an appearance at the dinner table. Let’s hope so, as vitamin-C-rich cranberries would certainly have done the pilgrims some good, scurvy being a major problem back then.

Here’s to your health

Speaking of maladies, here’s a fine topic for holiday dinner conversations: urinary tract infections (UTI). While UTIs were surely the least of the pilgrims’ health woes, they’re fairly common in modern times (especially among women) and there’s some evidence that cranberries may be helpful in preventing them.

UTIs are caused by bacteria (usually E. coli) getting into the urinary system. In most cases, such infections are contained to the urethra and bladder and can be treated with antibiotics. However, they can cause an array of uncomfortable symptoms (pelvic pain, burning sensation while urinating, etc.) and, in unluckier individuals, they have a tendency to recur.

Maybe you’ve heard that studies have suggested that regular consumption of cranberry juice may help prevent their recurrence. But it turns out that more recent suggest say that cranberries may not be much of UTI fighter after all. The research results are mixed and the mechanism of action is still a little fuzzy. For a while it was thought that cranberries worked by rendering urine too acidic for bacteria to set up camp in the urethra. More recently, the idea was that chemicals found in cranberries called proanthocyanidins (PACs) prevented bacteria from adhering to the cells lining the urinary tract. Essentially, it’s complicated.

But maybe you just like cranberries and want to give preventative medicine a shot. What have you got to lose, right? Well, a few considerations might be in order. First, go easy on the dosage, especially if you’re working with pure cranberry juice (most often, the stuff is sold in highly dilute “juice cocktail” form). Like Thanksgiving itself, excessive amounts of cranberries can cause stomach upset. Additionally, the fruit may (this too is still in the “more research is needed” category) have an undesired interaction with the prescription anticoagulant (translation: blood clot preventing drug) warfarin. While it hasn’t been demonstrated with any certainty, coupling daily cranberry juice consumption with your warfarin regimen may put you at greater risk for bruising and bleeding.§

But you might be over-thinking all this. Maybe you should just relax and have a glass of cranberry wine. You can even make it at home. Though you should probably start immediately as the fermenting and “racking” process takes about a year. And then, it should probably sit for another year. If you get your act together quickly enough, you might be able to enjoy cranberry wine at Thanksgiving 2013. Something to look forward to.

* While they’re not the only floating fruit, cranberries are particularly skilled at it. As for other fruits, I can report that (according to internet research) lemons float, whereas limes sink, and that (according to kitchen experiments) red grapefruits float, but not by much.

† Tannins also provide a much more welcome dryness to wine.

‡ Thanksgiving did not become official in the U.S. until 1863 – almost two and a half centuries after the settlers’ famous party – when Abraham Lincoln made it a national holiday.

§ These are already side effects of warfarin (it does impede blood from clotting after all), cranberry juice might just amplify them. Maybe. Bonus trivia: warfarin can also be used as rat poison.

This post was originally published in November 2011