Circadian rhythms are physical, mental and behavioral changes that follow a roughly 24-hour cycle, responding primarily to light and darkness in an organism’s environment.

Our biological clocks drive our circadian rhythms. These internal clocks are groupings of interacting molecules in cells throughout the body. A “master clock” in the brain coordinates all the body clocks so that they are in synch.

At the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), Mike Sesma tracks circadian rhythm research being conducted in labs across the country, and he shares four timely details about our internal clocks:

They’re incredibly intricate.

Biological clocks are composed of genes and proteins that operate in a feedback loop. Clock genes contain instructions for making clock proteins, whose levels rise and fall in a regular cyclic pattern. This pattern in turn regulates the activity of the genes. Many of the results from circadian rhythm research this year have uncovered more parts of the molecular machinery that fine-tune the clock.

Every organism has them – from algae to zebras.

Many of the clock genes and proteins are similar across species, allowing researchers to make important findings about human circadian processes by studying the clock components of organisms like fruit flies, bread mold and plants.

Whether we’re awake or asleep, our clocks keep ticking.

While they might get temporarily thrown off by changes in light or temperature, our clocks usually can reset themselves.

Nearly everything about how our body works is tied to biological clocks.

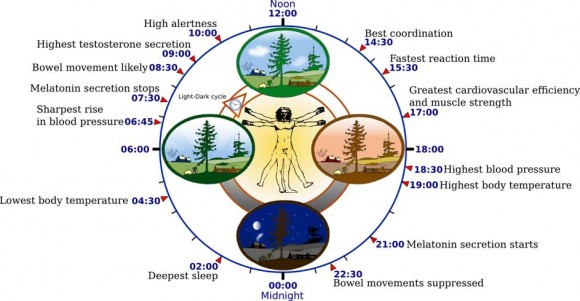

Our clocks influence alertness, hunger, metabolism, fertility, mood and other physiological conditions. For this reason, clock dysfunction is associated with various disorders, including insomnia, diabetes and depression. Even drug efficacy has been linked to our clocks: Studies have shown that some drugs might be more effective if given earlier in the day.

Here are four more interesting pieces of info on our biological clock, from the National Institute of Health’s Circadian Rhythm fact sheet:

What is the master clock?

The “master clock” that controls circadian rhythms consists of a group of nerve cells in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN. The SCN contains about 20,000 nerve cells and is located in the hypothalamus, an area of the brain just above where the optic nerves from the eyes cross.

How do circadian rhythms affect body function and health?

Circadian rhythms can influence sleep-wake cycles, hormone release, body temperature and other important bodily functions. They have been linked to various sleep disorders, such as insomnia. Abnormal circadian rhythms have also been associated with obesity, diabetes, depression, bipolar disorder and seasonal affective disorder.

How are circadian rhythms related to sleep?

Circadian rhythms are important in determining human sleep patterns. The body’s master clock, or SCN, controls the production of melatonin, a hormone that makes you sleepy. Since it is located just above the optic nerves, which relay information from the eyes to the brain, the SCN receives information about incoming light. When there is less light—like at night—the SCN tells the brain to make more melatonin so you get drowsy.

How are circadian rhythms related to jet lag?

Jet lag occurs when travelers suffer from disrupted circadian rhythms. When you pass through different time zones, your body’s clock will be different from your wristwatch. For example, if you fly in an airplane from California to New York, you “lose” 3 hours of time. So when you wake up at 7:00 a.m., your body still thinks it’s 4:00 a.m., making you feel groggy and disoriented. Your body’s clock will eventually reset itself, but this often takes a few days.

Bottom line: After we set the clocks back – or forward – our body’s biological clock needs time to adjust. A list of facts about how this internal clock works.