First things first; anyone who is at all squeamish about intestinal bacteria, fecal transplants, or stomach surgery may want to leave the room now. Off you go. The rest of us will be discussing a new study, published last week in Science Translational Medicine, that some believe may lead to treatments for obesity that offer the benefits of surgical intervention without all the slicing and stitching.

The specific surgery is Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), the most commonly used surgical weight loss technique in the U.S. The procedure divides the stomach into upper and lower portions, connecting the upper directly to the small intestine and thus drastically shrinking usable stomach size. The results are impressive. Obese patients who undergo RYGB lose more weight and do so faster than those attempting to slim down by dieting. That’s not surprising, as the rerouting of the digestive tract not only yields a stomach that holds less food, it also reduces the length of intestine in which calories can be absorbed. But changes in gut microbe populations of RYGB patients have also been noted, and there was reason to believe that these changes could contribute to the striking post-surgical weight loss.

The trouble with crediting microbial shifts for surgical success is that various other factors, including diet, also affect the distribution of our gut flora. Sure, RYGB patients experience changes in gut microbes, but are these changes caused by the surgical remodeling of the digestive tract, or do they result from the accompanying weight loss? Or perhaps such changes are merely a byproduct of the physiological disruption of any such surgery? To address these questions, researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University – who presumably had the dexterity of those street artists who can paint your name on a grain of rice – performed teeny tiny gastric bypasses on obese mice and tracked the post-surgical outcomes.

Not all mice received a proper RYGB, a subset were instead subjected to “sham” surgery, in which parts of the digestive tract were cut but then just stitched back together without the elaborate rerouting (and thus without the desired weight loss). Of the unfortunate shammed animals, a portion were also placed on a reduced calorie diet following surgery so that their weights would match those of the group slimmed by RYGB. Got all that? Surgery for everyone; useful surgery for some, pointless surgery or pointless surgery plus dieting for others.

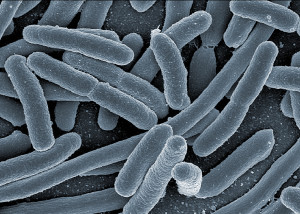

After the mice recuperated from surgery, the researchers spent 3 months monitoring their weight and analyzing fecal samples. As they predicted, the microbial population of the RYGB poo was the most radically transformed, while that of the sham poo changed only modestly. And while sham surgery + diet mice also crapped out a somewhat altered array of microbes, there were changes in the RYGB microbial population that were not obtained by dieting alone. Both the RYGB and sham surgery + dieting mice lost weight, the RYGB microbes weren’t simply those of thin mice; they were a unique population.

It is, however, the second act of the experiment that has created the bigger stir. In this part the team collected gut microbes from each of the three surgically altered groups of mice and fed them to thin, non-operated, “germ free” mice (i.e., animals raised to have no gut microbes). And what happened? If you guessed no significant change for animals fed the sham microbes but a notable (5 percent) weight reduction in the group given RYGB microbes, you get a gold star. And let me reiterate that these were thin mice receiving the “donated” gut microbes, not obese mice. When inoculated with microbes from mice that underwent RYGB surgery, thin mice got thinner. This supports the idea that the post-RYGB gut microbes differ from those of animals thinned by diet. It also gets everyone’s hopes up for the ultimate have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too medical treatment – gastric bypass sans surgery.*

To be clear, a surgery-free bypass is a possibility, not an inevitability. This kind of microbial transplant has yet to be tested on obese mice, much less obese humans. But despite the fuzzy and far away nature of the innovation, I’ve already got my caveats. So join me if you will for a stroll along the path of apprehensive speculation.

My main concern is that we still don’t know exactly how RYGB-created microbial populations contribute to weight loss. Weight loss following RYGB can be attributed to changes in both energy in (calories absorbed) and energy out (calories burned). So microbes may affect metabolic rate, or calorie absorption, or quite possibly both. And calories aren’t the only thing absorbed as food molecules make their way through our intestines. There are nutrients involved too. Reducing absorption can be both pro and con, and RYGB patients do have to watch out for nutritional deficiencies. They’re also at increased risk for bone fractures. If microbes account for some of the beneficial weight loss of RYGB, might they also contribute to some of these problems? I’d say it’s worth a study or two.

And what happens if we do produce a treatment that offers surgery-sized weight loss without the actual surgery? True, most people aren’t ecstatic at the thought downing an infusion of someone else’s fecal microbes, but it’s still less prohibitively terrifying than having your digestive tract chopped up and reassembled. It’s easy to see how a microbial procedure could be more widely applied than a surgical one, and if it comes with any of the surgical downsides, that may not be a good thing. A microbial potion for clinically obese individuals who would otherwise risk surgery? That sounds great. Let’s do it. But the same concoction given to people who are only moderately overweight and would normally receive the more conservative treatment of diet and exercise? Here my enthusiasm wanes. I’ll stop short of envisioning a dystopian future where thin people swallow microbes in order to become thinner people. I’m not feeling that cynical today.

In any event, we’re still far from any of this becoming a reality. And at least microbial populations can potentially change over time. RYGB surgery, on the other hand, is irreversible.

*FYI, the “bypass” in gastric bypass refers to the fact that when the upper stomach is surgically connected to the small intestine, the first portion of the intestine in bypassed. So we probably shouldn’t get into the habit of referring to “surgery-free bypasses.” Just this once, ok?