The 2008 Chinese milk scandal was one of the worst food poisoning fiascos on record. An estimated 300,000 children and infants became ill, and at least six died, after ingesting milk or powdered infant formula tainted with melamine. Worse still, the chemical didn’t enter the food supply by chance or even passive neglect, it was deliberately added to the products by multiple companies. An article in the journal Science in 2008 described the operation as “nothing short of a wholesale re-engineering of milk.” While the scope of the tragedy was shocking, there was another worrying element to the case – only a fraction of the children who ingested the tainted milk products actually got sick. How could a chemical be acutely toxic to some without causing as much as a tummy ache in others? From the beginning there were doubts that melamine had acted alone in the poisoning. And now scientists believe that it had an accomplice not within the adulterated milk but in the bodies of the victims themselves, specifically the bacteria residing in their intestines.

Melamine isn’t the kind of classic poison you’d find in an Agatha Christie novel. It’s an industrial chemical used as a flame retardant and plastic stabilizer (the first time I saw the word was on the back of a plate at a Thai restaurant). In fact, it’s not even especially poisonous, requiring hefty doses to kill rodents and presumably humans. The companies stirring melamine into milk probably didn’t think it would do any harm. They were adding it for the unscrupulous but non-murderous purpose of increasing profits by sneaking watered down milk past protein spot checks.* And for the most part unsuspecting consumers just got a product with inferior nutritional content to bring home to their families. But about one percent of the children served melamine-laced milk products developed dangerous kidney problems, including kidney stones.

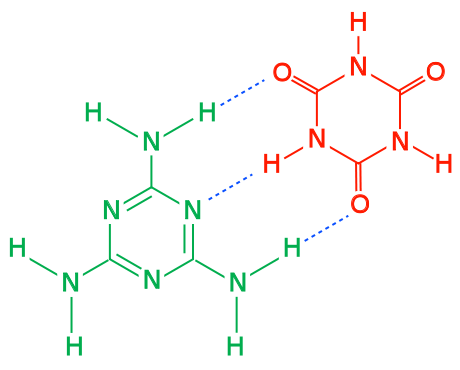

This wasn’t the first time melamine contamination had been linked to kidney injury. In 2007, the deaths of dozens of pets in North America sparked a recall of cat and dog food from various manufacturers. All shared a common ingredient, wheat gluten from China that contained melamine. But, unlike the milk, the pet food was found to contain an additional contaminant – cyanuric acid. When combined with melamine, cyanuric acid crystalizes and can form kidney stones.

While initial tests of the melamine-tainted milk failed to find cyanuric acid, it may have still played a role in the 2008 poisoning. Cyanuric acid, it turns out, can also be synthesized from melamine. Not only that, the transformation can be achieved by certain bacteria that produce cyanuric acid as a byproduct of melamine metabolism (i.e., they eat melamine and crap out cyanuric acid). And this is where the current study – published February 13, 2013 in the journal Science Translational Medicine – comes in.

Working on the suspicion that gut bacteria of the human victims facilitated the 2008 milk poisonings, researchers at the University of North Carolina Greensboro and the Shanghai Jiaotong University performed a series of experiments using rats to test this possibility. To begin, they fed rats high doses of melamine and gave some of them antibiotics. As you may recall from warnings about antibiotic overuse, these drugs have the unfortunate side effect of killing off normal gut microbes. In this case, however, the side effect was itself the goal. Melamine-fed rats additionally dosed with antibiotics experienced less kidney damage than those given melamine alone. Fewer gut microbes, fewer kidney problems. Additionally the melamine + antibiotic rats had more melamine in their urine than the melamine alone group. So without enough gut microbes, melamine was more likely to just go in one end and out the other. But with the aid of gut microbes, it stuck around longer, possibly being converted into cyanuric acid and then incorporated into harmful kidney stones.

The team also looked at how melamine and gut bacteria interacted outside of rats. Since feces contain a healthy serving of gut bacteria, this was done by mixing rat droppings with melamine. As the ingredients were allowed to comingle, melamine concentrations in the samples decreased and cyanuric acid increased. As no cyanuric acid was detected in the poo-free control samples, these changes in concentration again appear to be the result of microbes turning melamine into cyanuric acid.

Of the bacteria isolated from the rat feces, species of the genus Klebsiella were especially adept at performing the melamine to cyanuric acid transformation. So the researchers decided to see if upping the numbers of these bacteria in rats’ intestines had any effect on melamine poisoning symptoms. Sure enough the kidneys of the rats fed melamine + Klebsiella bacteria (no antibiotics for anyone this time as we’re going for maximum microbes) were in even worse shape than those of the rats fed just melamine.

The collective results suggest that gut bacteria can influence melamine toxicity, at least in rats. But what about humans? The authors note that the percentage of humans found to have a species of Klebsiella (K. terrigena) living in their intestines is about one percent, very similar to the percentage of children affected by the melamine-contaminated milk.

While the numbers don’t contradict the possibility that gut bacteria accounted for the sickening of only some children in the 2008 poisoning, it’s difficult to establish a direct correlation. Analyzing fecal samples of the surviving victims is certainly not impossible, but it wouldn’t necessarily clarify much. Gut microbe populations can change over time, altered by diet and age. Over four years have passed since the melamine-laced milk did its damage. It’s a bit late to start cataloging bacteria now.

But beyond the 2008 milk poisoning episode, this study adds to a growing understanding of importance of the microbial residents in our guts. They’ve been shown to contribute to the metabolism of food and calorie absorbtion, but they may play also play a role in food and drug safety. What constitutes a safe chemical may vary from person to person depending on their microbial makeup. When taking medicines, we worry about their interactions with other drugs and even with food (no grapefruit with your statins please… and a host of other pills). But as we learn more about gut microbes, we may have to revise some of our warning labels:

Take 1 tablet twice daily with water. Avoid exposure to direct sunlight. Do not take if pregnant, breastfeeding, or colonized by certain intestinal bacteria.

* To determine protein content, the test just looks for nitrogen (a component of amino acids). So while lacking in protein, melamine contains enough nitrogen to boost milk’s perceived protein count.