By Michon Scott and Rebecca Lindsey, via NOAA Cimate.gov

Our planet probably experienced its hottest temperatures in its earliest days, when it was still colliding with other rocky debris (planetesimals) careening around the solar system. The heat of these collisions would have kept Earth molten, with top-of-the-atmosphere temperatures upward of 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (7,538 C.)

Even after those first scorching millennia, however, the planet has sometimes been much warmer than it is now. One of the warmest times was during the geologic period known as the Neoproterozoic, between 600 and 800 million years ago. Another “warm age” is a period geologists call the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, which occurred about 56 million years ago.

History of hot

Temperature records from thermometers and weather stations exist only for a tiny portion of our planet’s 4.54-billion-year-long life. By studying indirect clues—the chemical and structural signatures of rocks, fossils, and crystals, ocean sediments, fossilized reefs, tree rings, and ice cores—however, scientists can infer past temperatures.

None of that helps with the very early Earth, however. During the time known as the Hadean (yes, because it was like Hades), Earth’s collisions with other large planetesimals in our young solar system — including a Mars-sized one whose impact with Earth is thought to have created the moon — would have melted and vaporized most rock at the surface. Because no rocks on Earth have survived from so long ago, scientists have estimated early Earth conditions based on observations of the moon and on astronomical models. Following the collision that spawned the moon, the planet was estimated to have been around 2,300 degrees Kelvin (3,680 F.)

Even after collisions stopped, and the planet had tens of millions of years to cool, surface temperatures were likely more than 400° Fahrenheit. Zircon crystals from Australia, only about 150 million years younger than the Earth itself, hint that our planet may have cooled faster than scientists previously thought. Still, in its infancy, Earth would have experienced temperatures far higher than we humans could possibly survive.

But suppose we exclude the violent and scorching years when Earth first formed. When else has Earth’s surface sweltered?

Thawing the freezer

Between 600 and 800 million years ago — a period of time geologists call the Neoproterozoic — evidence suggests the Earth underwent an ice age so cold that ice sheets not only capped the polar latitudes, but may have extended all the way to sea level near the equator. Reflecting ever more sunlight back into space as they expanded, the ice sheets cooled the climate and reinforced their own growth. Obviously, the Earth didn’t remain stuck in the freezer, so how did the planet thaw?

Even while ice sheets covered more and more of Earth’s surface, tectonic plates continued to drift and collide, so volcanic activity also continued. Volcanoes emit the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. In our current, ice-age-free world, the natural weathering of silicate rock by rainfall consumes carbon dioxide over geologic time scales. During the frigid conditions of the Neoproterozoic, rainfall became rare. With volcanoes churning out carbon dioxide and little or no rainfall to weather rocks and consume the greenhouse gas, temperatures climbed.

What evidence do scientists have that all this actually happened some 700 million years ago? Some of the best evidence is “cap carbonates” lying directly over Neoproterozoic-age glacial deposits. Cap carbonates—layers of calcium-rich rock such as limestone—only form in warm water.

The fact that these thick, calcium-rich rock layers sat directly on top of rock deposits left behind by retreating glaciers indicate that temperatures rose significantly near the end of the Neoproterozoic, perhaps reaching a global average higher than 90° Fahrenheit. (Today’s global average is lower than 60°F.)

The tropical Arctic

Another stretch of Earth history that scientists count among the planet’s warmest occurred about 55-56 million years ago. The episode is known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

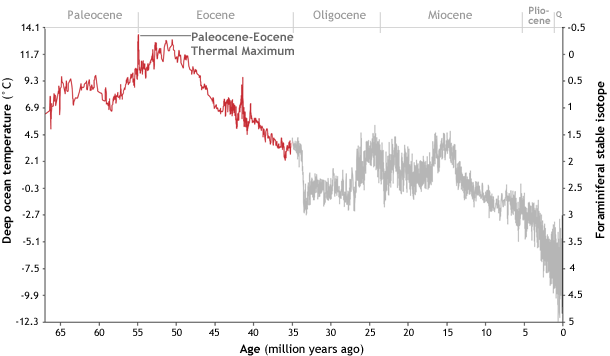

Stretching from about 66-34 million years ago, the Paleocene and Eocene were the first geologic epochs following the end of the Mesozoic Era. (The Mesozoic—the age of dinosaurs—was itself an era punctuated by “hothouse” conditions.) Geologists and paleontologists think that during much of the Paleocene and early Eocene, the poles were free of ice caps, and palm trees and crocodiles lived above the Arctic Circle. The transition between the two epochs around 56 million years ago was marked by a rapid spike in global temperature.

During the PETM, the global mean temperature appears to have risen by as much as 5-8°C (9-14°F) to an average temperature as high as 73°F. (Again, today’s global average is shy of 60°F.) At roughly the same time, paleoclimate data like fossilized phytoplankton and ocean sediments record a massive release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, at least doubling or possibly even quadrupling the background concentrations.

It is still uncertain where all the carbon dioxide came from and what the exact sequence of events was. Scientists have considered the drying up of large inland seas, volcanic activity, thawing permafrost, release of methane from warming ocean sediments, huge wildfires, and even—briefly—a comet.

Like nothing we’ve ever seen

Earth’s hottest periods — the Hadean, the late Neoproterozoic, the PETM — occurred before humans existed. Those ancient climates would have been like nothing our species has ever seen.

Modern human civilization, with its permanent agriculture and settlements, has developed over just the past 10,000 years or so. The period has generally been one of low temperatures and relative global (if not regional) climate stability.