Modern earthquakes as aftershocks

The central United States and eastern Canada and U.S. are not earthquake hotbeds. Scientists considered these areas “stable” because of their low seismic activity. Still, these regions do occasionally see small quakes. On November 13, 2023, a team of scientists said that many of these temblors are probably aftershocks from big earthquakes that occurred more than 100 years ago.

Yuxuan Chen of Wuhan University in China and lead author of the new study said:

Some scientists suppose that contemporary seismicity in parts of stable North America are aftershocks, and other scientists think it’s mostly background seismicity. We wanted to view this from another angle using a statistical method.

Their results suggest that some of the modern-day earthquakes around the New Madrid region (where Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee and Kentucky meet) between 1980 and 2016 were likely aftershocks of quakes from the 1800s. In addition, the 1886 Charleston earthquake in South Carolina is also still producing aftershocks today. But meanwhile, they found that the aftershock activity from the 1663 Charlevoix, Quebec, earthquake has ended.

The 2024 lunar calendars are here! Best Christmas gifts in the universe! Check ’em out here.

The scientists published their study in the peer-reviewed Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth on November 7, 2023.

What are aftershocks?

When a big earthquake hits an area, aftershocks, or smaller quakes, rumble in the days, weeks and months that follow. And now, the study has shown, they can occur even hundreds of years after the initial quake. Aftershocks are part of a fault’s readjustment process. Even though aftershocks are smaller, they can still be damaging.

When smaller quakes strike, it’s important to know if these could be foreshocks preceding a bigger quake. Or, whether they are background seismicity (the normal amount of seismic activity for a given region) or aftershocks. Unfortunately, according to the USGS, we can’t yet tell the difference between foreshocks and background seismicity until after the larger earthquake strikes.

So, knowing what causes today’s earthquakes – whether they are aftershocks or not – will help scientists understand the future risk for these regions.

Studying earthquakes

The scientists looked at three locations of the largest earthquakes in recent history for the stable area of North America. The first was a 1663 earthquake of around magnitude 7 in Charlevoix, Quebec, just north of Maine. Next were four earthquakes in the New Madrid seismic zone around the Mississippi River in the Central U.S. These earthquakes struck over the years of 1811 and 1812 and ranged from approximately magnitudes 7 to 8.6. Lastly, the team looked at an 1886 earthquake that hit Charleston, South Carolina, at around a magnitude of 7.

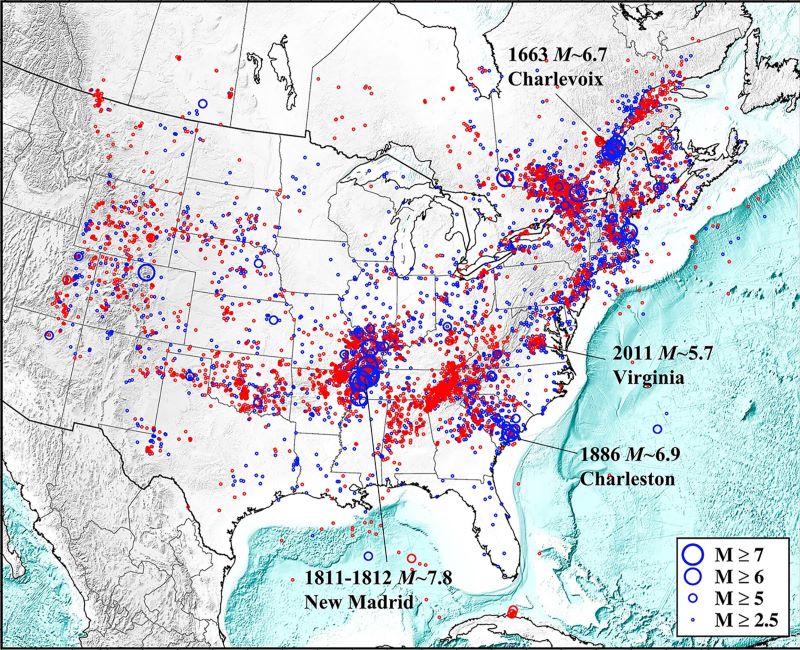

As you can see from the map below, these regions are not near the edge of a plate boundary. This is why they are considered stable regions. Because there are less earthquakes here, it raises more questions about their origins.

So, the team wanted to figure out which modern-day quakes might be aftershocks. Aftershocks cluster around the epicenter of the original earthquakes. Therefore, they focused on all earthquakes within a 155-mile (250-km) radius of the large quakes mentioned above. They also limited themselves to modern earthquakes that were at least magnitude 2.5.

The nearest neighbor method

The scientists used a statistical algorithm called the nearest neighbor method in their research. Chen explained:

You use the time, distance and the magnitude of event pairs, and try to find the link between two events … that’s the idea. If the distance between a pair of earthquakes is closer than expected from background events, then one earthquake is likely the aftershock of the other.

Aftershocks would be those earthquakes that occurred close to the original epicenter and before the background seismicity has resumed.

Using the nearest neighbor method, the team found that the regions that had large earthquakes in the 1800s were still experiencing aftershocks. But the region around the 1663 earthquake was now showing just background seismicity. The study concluded that around 30% of seismicity between 1980 and 2016 in the New Marid seismic zone is likely aftershocks of the four large earthquakes that occurred there in 1811–1812. But that percentage could be as high as 65%. And in South Carolina, approximately 16% of today’s earthquakes are aftershocks from 1886. However, the aftershock activity of the 1663 Quebec earthquake has ended.

Susan Hough, a geophysicist with the USGS who was not involved in the study, said:

To come up with a hazard assessment for the future, we really need to understand what happened 150 or 200 years ago. So bringing modern methods to bear on the problem is important.

Bottom line: Scientists examined modern-day earthquakes in three stable regions of North America and found that some of them are aftershocks from large earthquakes that struck in the 1800s.

Source: Long-Lived Aftershocks in the New Madrid seismic Zone and the Rest of Stable North America

Read more: The Ring of Fire, where volcanoes and earthquakes reign