Beautiful, exotic lionfish – with no natural predators due to their extraordinary painful venom – are believed to have entered the western Atlantic sometime in the mid-1980s. Aquarists who no longer wanted them released them into the sea. An aquarium holding lionfish was destroyed by Hurricane Andrew in 1992, possibly allowilng some lionfish to escape into Atlantic waters off south Florida. Lionfish now range from as far north as Bermuda and the North Carolina coast, to as far south as Venezuela, including the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. They’ve become a dreaded, invasive ecological menace in the western Atlantic Ocean, responsible for steep declines in native fish populations, as much as 95 percent in some places. Now new research, published in the journal Ecological Applications, shows that controlling lionfish populations with persistent hunting can help native fish rebound.

Stephanie Green, a newly-minted PhD marine ecologist at Oregon State University and lead author of the paper, said in a press release:

This is excellent news. It shows that by creating safe havens, small pockets of reef where lionfish numbers are kept low, we can help native species recover.

And we don’t have to catch every lionfish to do it.

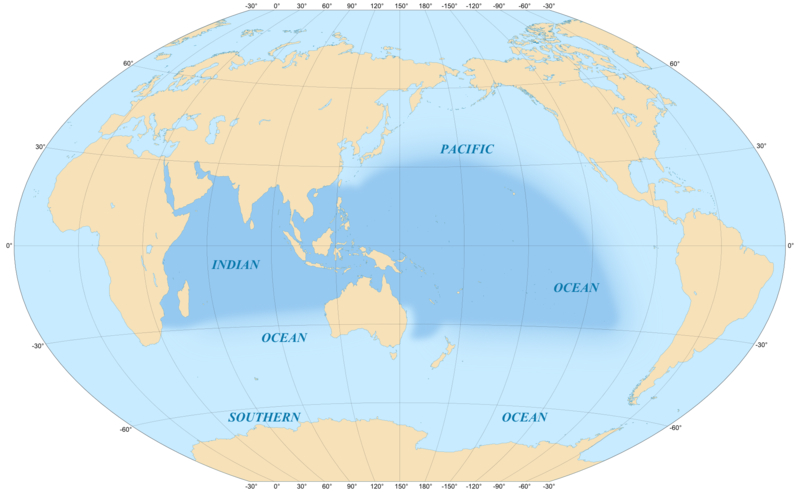

It’s impossible to completely eradicate lionfish, whose native habitat is in the Indo-Pacific. Except for the humans that hunt them down, nothing stands in their way. Lionfish have an aggressive disposition, and are protected by venomous spines that make them unappetizing to potential western Atlantic predators. They eat anything smaller than themselves, a diverse diet that includes other fish, shrimp, crab, and octopus. When necessary, lionfish can go without food for long periods of time, giving them yet another edge over native fish species. They’re also able to live in deep waters that are not easily accessible to divers.

Efforts to control lionfish populations, usually with divers that hunt them with spears and nets, had long been regarded as an exercise in futility. But the new study, that used computer modeling and field tests, shows that the reduction in lionfish numbers at some marine sites have led to the recovery of native fish species.

For instance, at several study sites, researchers found that reducing lionfish populations by about 75 to 90 percent led to the quick recovery of native fish numbers, an increase of about 50 to 70 percent. Among the native fish making a comeback are species valued by local island communities, such as Nassau grouper and yellowtail snapper.

Meanwhile, in areas where lionfish were not hunted, there was a continued decline in native fish species.

Dr. Isabelle Côté, at the Simon Fraser University in Canada, and also Green’s thesis advisor, said in another press release:

Many researchers in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and U.S. Atlantic coastal regions are removing lionfish, but there has been little research verifying whether control is effective at recovering and protecting native fish.

Our study is the first to show that control can be effective and that native fish will return to reefs once lionfish are removed. We are also the first to provide a way to determine how much lionfish control is needed.

The researchers claim, in their paper, that the lionfish culling strategy that is currently underway in some marine locations could also be applied to other lionfish habitats such as temperate waters with rocky ocean floors, estuaries, seagrass meadows, and mangroves. They recommend that marine reserves, generally “No Fishing” zones, need to make lionfish removal a priority in order to conserve native fish populations. Mangroves, which are important nurseries for many ocean fish species, also need special protection.

In their paper, the scientists noted:

Many invasions such as lionfish are occurring at a speed and magnitude that outstrips the resources available to contain and eliminate them. Our study is the first to demonstrate that for such invasions, complete extirpation is not necessary to minimize negative ecological changes within priority habitats.

Bottom line: Lionfish, an invasive exotic fish species to western Atlantic coastal waters, have caused a significant decline in native fish in the western Atlantic. They have no predators to keep their numbers in check due to their aggressive behavior and venomous spines. In the journal Ecological Applications, scientists report that even though lionfish cannot be completely eradicated, controlling their population through hunting can help re-establish native fish species.