Well known for their intelligence, flexibility and dexterity – as well as their ability to change the color, patterning, and texture of their skin – octopuses are masters of camouflage. New research shows that the skin of an octopus does more. It actually can sense and respond to light directly, without input from the eyes or brain. Evolutionary biologists Desmond Ramirez and Todd Oakley of University of California conducted this research, which was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology on May 15, 2015.

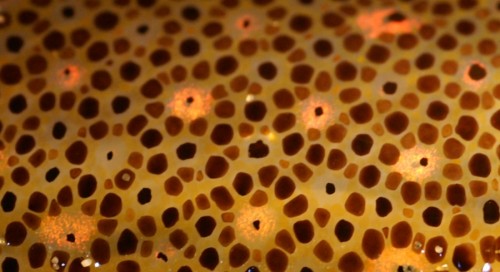

Octopuses change skin color with the aid of specialized cells called chromatophores, located beneath their skin.

Each of these cells has contains pigments, used to produce color, surrounded by a ring of muscle. When these tiny muscles are commanded by the octopus’ brain to relax or contact, the color becomes more or less visible. In this way, an octopus can produce a wide variety of texture and color patterns in their skin, enabling them to blend into their environment.

Scientists thought this process relied mainly on the eyes of an octopus, with its vision detecting the colors in its surroundings and thereby controlling the stimulation of the chromatophores.

But previous reports – based on skin biopsies of squid – did exist that described these structures reacting to light without input from the creature’s eyes or brain. Now that previous work has been confirmed.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Ramirez and Oakley collected skin biopsies from California two-spot octopuses and proceeded to experiment on their independent reaction to light exposure. They first exposed the tissue to white light and observed that the chromatophores first expanded, and then, with the light’s absence, contracted.

Then they measured how long it took for the skin’s color to change with light across the visible light spectrum, ranging in color from violet to orange. They observed the swiftest response in the skin to blue light.

The response to blue light correlated with a known peak responsive wavelength for opsin, a protein in the eye of an octopus that forms part of its ability to sense light. These proteins are usually found in the eye’s retina and are involved in converting light photons to electrochemical signals, in other words, signals in the nervous system that tell the muscles how to behave.

Ramirez and Oakley then tested the skin of their octopus samples for opsin. They found similar proteins that were localized to sensory neurons distributed on the skin surface. They said that – instead of opsin organizing light in the photoreceptor cells in the eye of the octopus – chromatophores in the skin of the octopus are arranged loosely and detect changes in brightness, rather than a detailed image.

As light from the environment strikes the opsins in the skin of an octopus, the scientists said, the light directly stimulates the expansion or contraction of the chromatophores. The scientists call this behavior light-activated chromatophore expansion (or LACE). They wrote in their paper:

LACE in isolated preparations suggests that octopus skin is intrinsically light sensitive and that this dispersed light sense might contribute to their unique and novel patterning abilities.

Bottom line: New research from evolutionary biologists Desmond Ramirez and Todd Oakley of University of California shows an octopus can change skin color in response to light, without input from the eye or brain.