NASA drought research

NASA said on September 8, 2021, that – according to NOAA – seasonal summer rains have done little to offset drought conditions gripping the western United States. California and Nevada both saw record July heat and moderate-to-exceptional drought. New NASA research now shows how drought in the region is expected to change in the future. The study found that the western U.S. is headed for prolonged drought conditions. That’s the case, according to this study, whether greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb or are aggressively reined in.

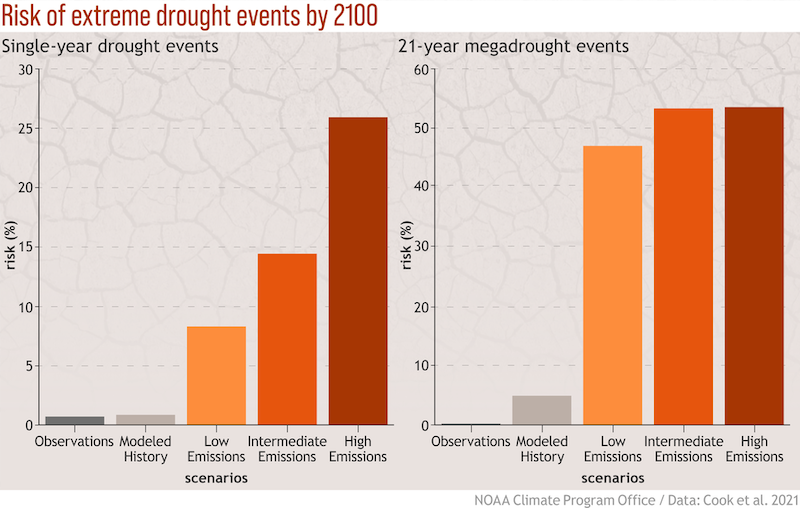

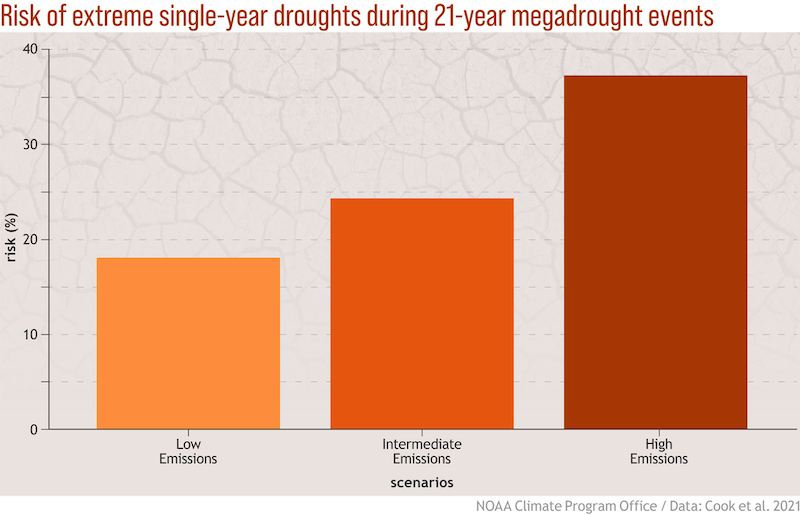

But the study also showed that the severity of acute, extreme drought events – and the overall severity of prolonged drought conditions – could be reduced with emissions-curbing efforts, as compared with a high-emissions future. This is important information for decision-makers considering two tools to reduce climate impacts: adaptation and mitigation. NASA said the new work will:

… provide stakeholders with crucial information for decision-making.

Scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) led the new study. It is published in the peer-reviewed journal Earth’s Future.

Adaptation and mitigation

Adaptation is a term used by the scientific community and policymakers to describe policies that address impacts that will occur or are already occurring. For example, adaptation to rising sea levels might include relocating low-lying infrastructure.

Mitigation refers to efforts to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Mitigation can limit the severity of future impacts or even prevent them from happening by limiting how much the climate changes. Switching to cleaner energy sources and reducing greenhouse warming-driven ice melt are examples of mitigation to sea-level rise.

Rather than representing competing options, adaptation and mitigation can both be used to address climate impacts, NASA said. This new research shows how the two can complement each other when it comes to drought. Ben Cook, a research scientist at GISS and an adjunct associate research scientist at Columbia University, said:

Mitigation has clear benefits for reducing the frequency and severity of single-year droughts. We may have more of these 20-year drought periods, but if we can avoid the really sharp, short-term, extreme spikes, then that may be something that’s easier to adapt to.

Natural and human-caused climate change

Both acute single-year and prolonged multi-year droughts occur naturally due to variations in ocean currents, precipitation, and other factors. But human-caused climate change is turning up the heat in addition to these natural variations. It’s causing even more water to evaporate from plants and soil. The result is increased dryness, even in the absence of major precipitation deficits.

The scientists who conducted the new study wanted to understand the vulnerability and tendency towards drought in the U.S. Southwest, and the factors contributing to it. So the team selected the severe single-year drought of 2002 and the extended drought of 2000 to 2020 as examples of acute and prolonged droughts, respectively. Then they looked at how common these acute and prolonged droughts were. They looked not only during the period of instrumental records, but also using reconstructed drought conditions stretching back more than 1,000 years. And they looked at state-of-the-art supercomputer simulations of the future.

Past and present droughts

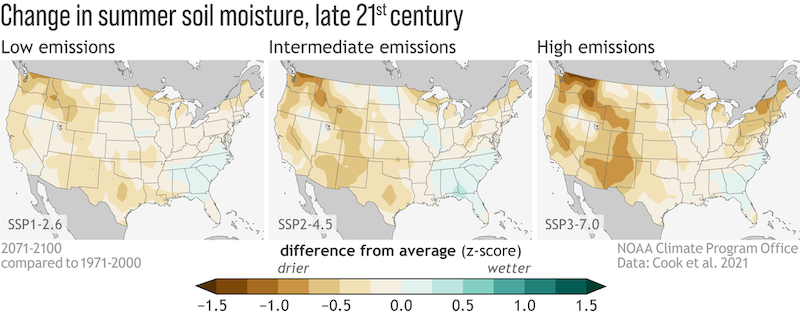

The team reconstructed soil moisture from the years 800 to 1900 CE using tree ring data from the region. The thickness of tree rings varies due to the wetness or dryness of each year. This provides scientists with a reliable way of estimating how much rain fell in a given year. For years after 1900, they used directly measured soil moisture values. To look at a range of possible futures, the team used data from the latest version of the Coupled Model Inter-comparison Project, or CMIP6. CMIP6 is an ensemble of climate model simulations that provide climate change projections depending on a range of possible greenhouse gas emission scenarios. CMIP6 enables scientists and policymakers to compare the impacts of different emissions policies directly. And it lets them see how, under different emissions scenarios, drought behaves differently.

The U.S. Southwest has been drought-prone for millennia. But warming temperatures dry the soil further. The region’s natural aridity becomes the backdrop for a higher risk of severe and prolonged droughts if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb. That’s according to Kate Marvel, a research scientist at GISS and Columbia University. She added:

The paleoclimate record shows that this region is prone to drought. There have been really, really severe droughts in the past: For instance, we know there were mega-droughts in the 13th century. But against the backdrop of natural climate variability – the things the climate would do even without human influence – we are confident increases in greenhouse gases make the temperature rise, and we’re fairly confident that increases drought risk in this region.

A future not set in stone

Understanding that increased drought can be expected under high and low emission scenarios alike has implications for adaptation strategies like rationing water usage and changing agricultural practices.

At the same time, the study’s finding that greenhouse emissions reductions still matter for extreme drought underscores the value of mitigation. Ko Barrett, senior advisor for climate in NOAA’s Office of Research and vice-chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report, said:

The ongoing southwestern drought highlights the profound effects dry conditions have on people and the economy. The study clearly highlights the impact that greenhouse gas mitigation could have on the occurrence and severity of Southwestern drought. It is not too late to act and blunt impacts like severe Southwestern drought periods and short-term drought events.

Marvel agreed. She added:

There’s going to be a new normal regardless. There’s going to have to be some adaptation to a drier regional climate. But the degree of that adaptation – how often these droughts happen, what happens to the drought risk – that’s basically under our control.

This new study was funded by NOAA’s Climate Program Office and NASA’s Modeling, Analysis, and Prediction Program.

Bottom line: New NASA drought research is showing how the U.S. Southwest might change in the future, under different scenarios of drought adaptation and mitigation.

Read more from EarthSky: The 2021 IPCC report: What you need to know