Plastic rain: More than 1,000 tons of microplastic rain onto western US

A new study estimates that more than 1,000 tons of microplastics from the air – equivalent to more than 123 million plastic water bottles – rain down onto protected areas in the western U.S. each year.

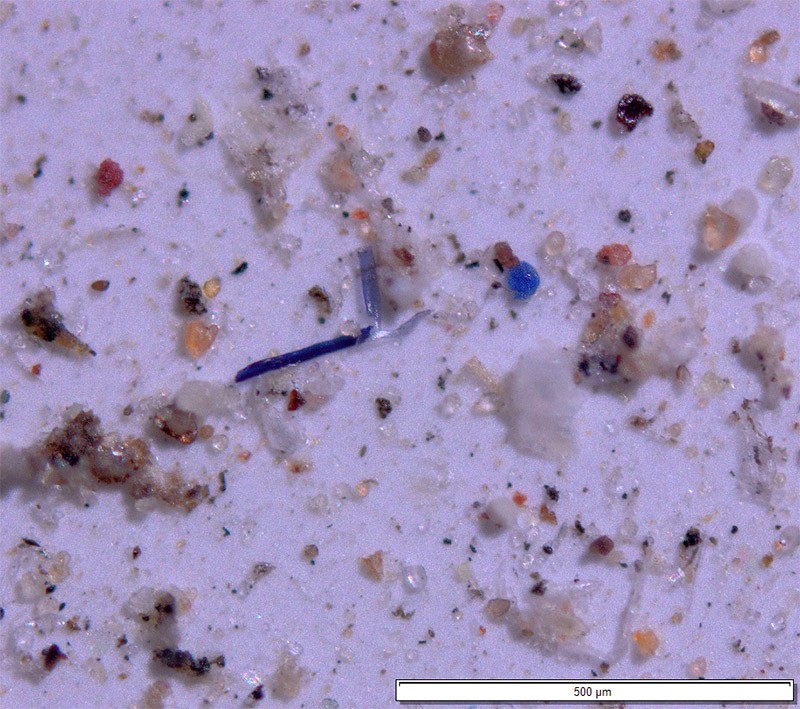

The discovery of the microplastics was a surprise. A research team was analyzing rainwater samples from national parks and wilderness areas across Colorado, as part of a pilot study on a new type of field equipment. They were shocked to find that the samples contained microplastics – plastic fragments less than 5 mm (.2 inch) in length – including a rainbow of plastic fibers, as well as beads and shards.

Utah State University assistant professor Janice Brahney is lead author of the study, published June 12, 2020, in Science. Brahney said in a statement:

We were shocked at the estimated deposition rates and kept trying to figure out where our calculations went wrong. We then confirmed through 32 different particle scans that roughly 4% of the atmospheric particles analyzed from these remote locations were synthetic polymers.

The world produced 348 million metric tons (over 7 billion pounds) of plastic in 2017, and global production shows no sign of slowing down. In the United States, the per capita production of plastic waste is 340 grams (12 ounces) per day. Although plastics’ high resilience and longevity make them useful in everyday life, these same properties mean that they fragment into tiny particles – microplastics – rather than degrade in the environment. These microplastics are known to accumulate in wastewaters, rivers, and ultimately the worlds’ oceans – and as Brahney’s team shows, they also accumulate in the atmosphere. Brahney said:

Several studies have attempted to quantify the global plastic cycle but were unaware of the atmospheric limb. Our data show the plastic cycle is reminiscent of the global water cycle, having atmospheric, oceanic, and terrestrial lifetimes.

The researchers examined the source and life history of microplastics that were deposited via rain versus via dry air. They found that nearby cities and population centers were the initial source of plastics in rain. In contrast, plastics from dry air showed indicators of long-range transport associated with large-scale atmospheric patterns. The researchers say this suggests that microplastics are small enough to be carried in the atmosphere across continents.

Most of the plastics deposited in both wet and dry samples were microfibers from clothing and industrial materials. Approximately 30% of the particles were brightly-colored microbeads, but not those commonly associated with personal care products. These microbeads were acrylic and likely derived from industrial paints and coatings. Other particles were fragments of larger pieces of plastic. The report notes:

This result, combined with the size distribution of identified plastics, and the relationship to global-scale climate patterns, suggest that plastic emission sources have extended well beyond our population centers and, through their longevity, spiral through the Earth system.

The researchers made weekly and monthly examinations of wet and dry samples from 11 sites, and estimate that more than 1,000 tons of microplastics are deposited onto protected lands in the western U.S. each year. A staggering 4% of the atmospheric particulates that the researchers identified collected in the samples from these remote locations were plastic polymers.

The ubiquity of microplastics in the atmosphere has unknown consequences for human and animal health, but the size ranges the researchers observed were well within that which accumulate in lung tissue.

Bottom line: Tons of microplastic particles carried in the aitmosphere have been discovered to fall on protected areas in the American West.

Source: Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States