There’s something otherworldly about jellyfish. They’re mesmerizing to watch, as they gracefully drift and gently pulse through the water, with tentacles wafting behind their bells. But don’t be fooled by their slow-motion swim; jellyfish are expert swimmers. A new study, published in January 2021 in the peer-reviewd journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, reinforced what scientists have known for some time, that some jellies are the most efficient swimmers in the world.

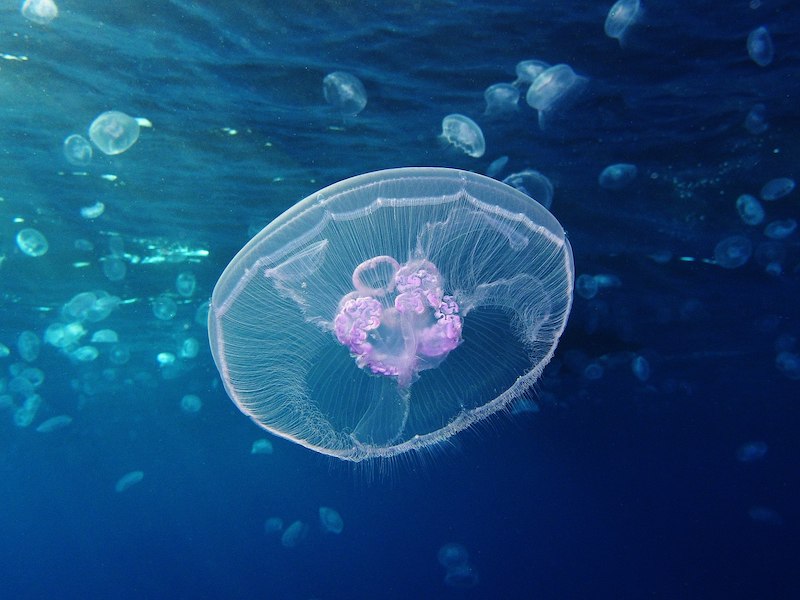

Jellyfish can be a catchall word for many invertebrates found drifting in the ocean. But most people associate that name with delicate gelatinous creatures that have an umbrella-shaped body and trailing tentacles. These types of jellies are known by their subphylum name, Medusazoa.

It’s a common misperception that jellies’ tentacles are used for swimming. They’re actually used to hold on to prey, and contain stinging cells that immobilize their catch. Tentacles are also used to defend against predators.

The real swimming action takes place in the jelly’s bell, where muscles contract to expel water, propelling the animal forward. But there’s also something else going on that makes jellies such energy efficient swimmers.

Want to see some jellyfish in action? Check out the jellyfish live cam from Monterrey Bay Aquarium, below:

Researchers at the University of South Florida, led by Brad Gemmell, studied moon jellies in an aquarium with tiny glass beads suspended in the water. High-speed cameras captured the movements of the glass beads as jellies swam past them. The beads revealed how water was displaced by the pulsing jellies.

Here’s what they learned: while pulsing through the water, when the jelly’s bell opens to the relaxed position, a vortex – a rolling movement of water – is formed along the edges of the bell. This loop of spinning water then gets trapped under the umbrella-like bell. When the bell contracts to expel water, a second vortex forms along the bell edges, this one spinning in the opposite direction. As the jelly moves forward, the first vortex loop, spinning in one direction, falls away from under the bell and meets the second vortex loop that’s spinning in the opposite direction.

Where the two opposing vortices meet, there is an increase in water pressure along that boundary, forming a short-lived “wall.” As water expelled by the jelly meets this fleeting ring-shaped barrier just below the jelly’s bell, it gives the animal an extra boost moving forward. Therefore, without expending additional energy, the jelly is able to move further than it would if it had started from rest.

In a statement, Gemmell reported that the jellies in motion that his team studied had a 41% increase in maximum swim speed and a 61% increase in total distance over a swimming cycle (a swim pulse), compared to those starting from rest.

Jellies have been around for about 500 million years, and today, there’s a stunning diversity of species adapted for life in all the oceans of the world, from the surface to the abyss, and even in some freshwater habitats. Their life cycle is quite extraordinary, starting out as larvae that settle on the substrate as polyps. Then, most species eventually transform into the medusa form – that’s the bell and tentacles form – and become free-swimming creatures. Some species, called stalked jellies, stay attached to the bottom.

If you’d like to learn more about jellyfish and their relatives, the comb jellies, check out this wonderful website by the Smithsonian Institution about these enigmatic creatures.

There are two live jelly cams at the Monterey Bay Aquarium! The moon jelly cam is featured at the top of the post. Here’s the sea nettle jelly cam. It’s mesmerizing!

Bottom line: Some jellyfish have evolved a unique way of swimming to move farther without expending additional energy, placing them with the world’s most efficient swimmers.

Source: The most efficient metazoan swimmer creates a ‘virtual wall’ to enhance performance