A decade ago, it was rare to hear a scientist link a specific climate event to ongoing, global, human-caused climate change. But the scientific language and processes for doing this have evolved, and now you do hear specific weather disasters discussed in terms of overall climate change. For the recent devastating flooding in south Louisiana (mid-August, 2016), a team of scientists from NOAA and the World Weather Attribution (WWA) has now said that human-caused climate warming increased the chances of the torrential rains that caused the foods by at least 40 percent, and possibly more. They conducted a rapid assessment of the role of climate change in the historic heavy rain event. As of August 17, Louisiana officials reported that the flood had killed 13 people, and that more than 30,000 had been rescued, more than 8,100 slept in shelters, and more than 60,000 homes had been damaged.

The rapid assessment study was submitted to the open access journal Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions. Read it here.

Karin van der Wiel, a research associate at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory is the study’s lead author. She said in a statement from NOAA:

We found human-caused, heat-trapping greenhouse gases can play a measurable role in events such as the August rains that resulted in such devastating floods, affecting so many people.

While we concluded that 40 percent is the minimum increase in the chances of such rains, we found that the most likely impact of climate change is a near doubling of the odds of such a storm.

The August storm started with a low-pressure system that carried massive levels of moisture from the unusually warm Gulf of Mexico over south Louisiana. The system stalled in the region around Baton Rouge, which led to record-breaking rainfall followed by inland flash flooding and river flooding.

Scientists speak of the return intervals for extreme climate events, such as the extreme rain and flooding in Louisiana. Return intervals are statistical averages over long periods of time, indicating that it’s possible, for example, to have more than one 30-year event in a 30-year period.

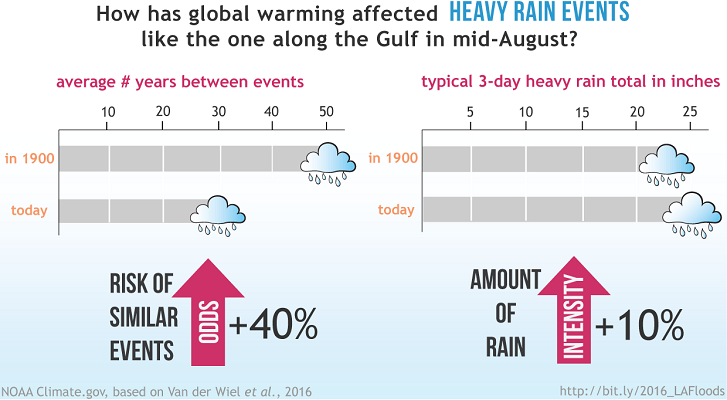

Computer models now indicate that the return interval for extreme rain events of the magnitude of the mid-August downpour in Louisiana has decreased from an average of 50 years to 30 years. Moreover, a typical 30-year event in 1900 would have had 10% less rain than a similar event today, for example, 23 inches instead of 25.

For their assessment, these scientists conducted a statistical analysis of rainfall observations and used two climate models to understand how the odds have changed for such three-day events between the early 20th century and the early 21st century. According to their statement:

The research focused on the central U.S. Gulf Coast, and investigated events as strong as that observed at the height of the storm (August 12-14) to provide a regional context and a broader assessment of risk.

The climate model experiments involved altering the climate based on levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, aerosols such as soot and dust, ozone and natural changes in the sun’s radiation and from volcanic eruptions for various periods of time to assess how extreme rainfall events respond to climate changes.

Bottom line: A study in Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussionssays that climate change increased chances of the August, 2016 record rains in Louisiana by at least 40 percent.

Read more about the Louisiana study from NOAA

Read more about how scientists link specific climate events to overall climate change, here.

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!