There is a notable dearth of archived recordings that capture female bird song, yet female bird song is quite common in nature. Scientists are now trying to rectify the situation and have established the Female Bird Song Project, a citizen science initiative, to help with this work. A paper describing their efforts was published in The Auk on March 14, 2018.

How to participate in the study

Many, but not all, female birds sing similar to male birds. Bird song, which differs from bird calls or general vocalizations, tends to have a structured rhythm to it. Birds mainly use song to attract mates, bond with other birds, and defend their territories.

Information on whether female bird song is present or absent in a species is currently available for only about one-fourth of all songbirds (suborder Passeri). In one recent survey of birds for which sex-specific singing behaviors were known, scientists found that a high proportion (64 percent) of the species had females that sing. This contradicts the erroneous and somewhat oft repeated phrase that only male birds sing. Indeed, female bird song seems to be quite prevalent, especially in tropical species.

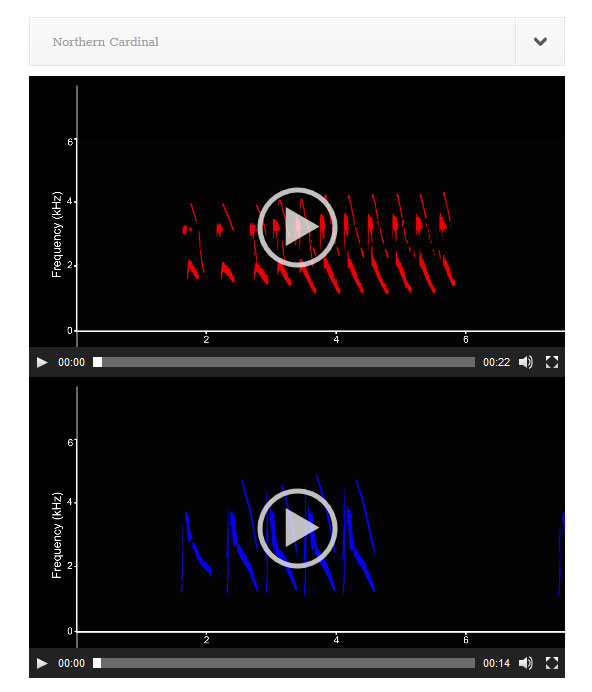

Some familiar temperate species in North America that exhibit female bird song include the black-capped chickadee, tufted titmouse, house wren, northern cardinal, song sparrow, dark-eyed junco, and yellow warbler. A more extensive, though still incomplete, listing of these North American birds can be found in the appendix published along with the new paper in The Auk, which is freely available online at the link here.

Female birdsong appears to have been a common ancestral trait that has been lost in several modern-day species, but scientists are unsure of why this happened. Thus, new data on female birdsong could help to advance our evolutionary knowledge of birds. Such data would also be important from a conservation perspective, as birdsong is often used to assess the health of bird populations.

The lack of female bird song in archived recordings may be due in part to geographical bias. Specifically, more intensive bird studies have been carried out in temperate regions than in tropical regions. Because female bird song appears to be more common in the tropics, the heavy research focus in temperate regions has served to perpetuate the false notion that female birdsong is less common than it actually is in nature. New data on female bird song in African, Asian, and Pacific Island species would be especially valuable, according to the scientists.

Karan Odom and Lauryn Benedict, co-authors of the new paper in The Auk, have recently established the Female Bird Song Project to help with the collection of new recordings. They explain the project’s purpose on their website:

Our goal is to increase awareness and documentation of female bird song for biodiversity collections so that we and other scientists can study this fascinatingly complex behavior. This citizen science project is part of an international research project involving researchers at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (USA) and Leiden University (The Netherlands).

The website of the Female Bird Song Project gives tips on how you can participate in these efforts, and there are even recordings of female birdsongs that you can listen to.

Collection of new female birdsong data is likely to yield many interesting findings in the years to come.

Bottom line: A new project aims to collect more recordings of female birdsong.