A three-year study to document the effects on sharks of catch-and-release sport fishing has found that some shark species don’t handle the trauma of being caught as well as others. Of the five sharks in the study, hammerheads fared the worst and were more likely than the others to not survive after being released back to the sea. Scientists published these findings in a special volume of the journal Marine Ecology Progress on January 29, 2014.

Operating in waters off south Florida and the Bahamas, scientists from the University of Miami conducted experiments that mimic catch-and-release fishing on five shark species: hammerhead, blacktip, bull, lemon, and tiger sharks. For each shark they landed, tests were performed to determine stress levels resulting from the shark’s battle with its angler.

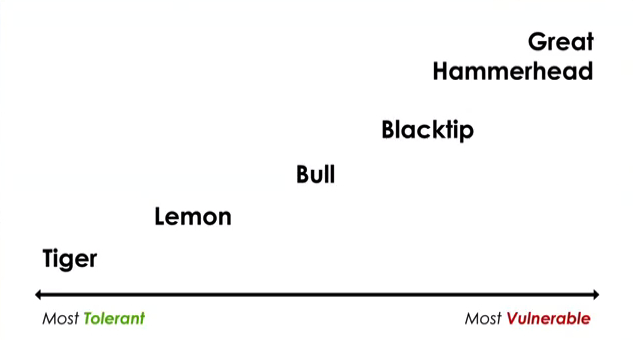

The five sharks displayed a range of responses to their ordeal. Blood tests showed tiger and lemon sharks to be quite resilient. Satellite tagging indicated they had no post-release mortality.

Hammerhead sharks, however, were found to be most adversely affected by the stress of fighting back on the fishing line. They had the highest blood lactic acid levels, an indicator of extreme physical exertion. This reflects the intrinsic high energy disposition of hammerhead sharks that are very strong and fast predators.

Satellite tracking also revealed that, compared to other shark species in the study, hammerheads had a higher incidence of death after release.

In the study, researchers examined the reflexes of the freshly-caught live sharks, for instance, observing how their eyes reacted to water sprayed from a syringe. Blood samples were drawn from each shark to measure its blood pH, as well as carbon dioxide and lactic acid levels. Before the sharks were returned to the ocean, they were fitted with satellite trackers to keep tabs on them after release.

Austin Gallagher, at the University of Miami and the paper’s lead author, commented in a press release:

Our results show that while some species, like tiger sharks, can sustain and even recover from minimal catch and release fishing, other sharks, such as hammerheads are more sensitive. Our study also revealed that just because a shark swims away after it is released, doesn’t mean that it will survive the encounter. This has serious conservation implications because those fragile species might need to be managed separately, especially if we are striving for sustainability in catch and release fishing and even in bycatch scenarios.

Neil Hammerschlag, of the University of Miami, added, in the same press release:

Many shark populations globally are declining due to overfishing. Shark anglers are some of the biggest advocates for shark conservation. Most have been making the switch from catch and kill to all catch-and-release. Our study helps concerned fisherman make informed decisions on which sharks make good candidates for catch-and-release fishing, and which do not, such as hammerheads.

More information is available in the video below.

Bottom line: Sharks caught during catch-and-release sports fishing have different responses to the stress of fighting against the fishing line. In a study to determine the physiological effects of stress due to line fishing, scientists found that most sharks showed high levels of lactic acid in their blood, and that hammerhead sharks were most sensitive and had a higher mortality rate after release. Results of their research were published in a special volume of the journal Marine Ecology Progress on January 29, 2014.