The Northern Cross is in the west now

A famous feature of the sky is that a huge cross stands upright as it goes down to set in the west. It’s in the constellation Cygnus the Swan. Cygnus is long line of stars as the bird’s neck and body, from Albireo (the beak) to Deneb (the tail). And an intersecting line forms the wings. Part of Cygnus is an asterism, or star figure, also known as the Northern Cross.

So conspicuous is this cross as it stands over the western horizon that travelers can use it as a compass. Polynesian navigators, and migrating birds, may have done so. It looms in the west for pilgrims making their way along the Camino de Santiago, as shown in my cover painting for Astronomical Calendar 2016.

Daniel Cummings raises the question: Since Cygnus is vertical as it sets in the west, why is it not also vertical as it rises in the east? The answer is not obvious or quick.

When does the Northern Cross rise and set?

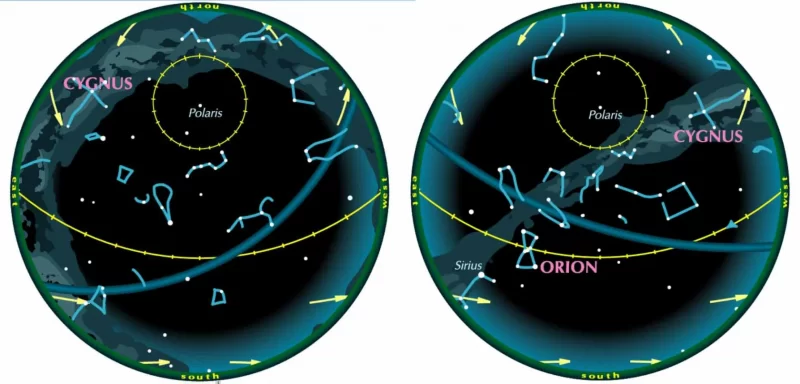

Here is the sky as Cygnus rises and sets, for places on Earth at latitude 40° north.

These sky domes are like those used on page 9 of Astronomical Calendar 2023 to show “How the sky changes for other latitudes.” In yellow are the Arctic circle, the celestial equator, and arrows showing how the sky rotates. The blue curve is the ecliptic. The Cygnus-rising scene is at sidereal hour 13, the setting scene at 3.

We can say that constellation Cygnus has an axis, an imaginary approximate line along its longer dimension, marked by the longer line of stars. This axis (which happens to lie along the Milky Way) is about parallel to the horizon when Cygnus is rising, vertical when Cygnus is setting.

How does it change for different latitudes?

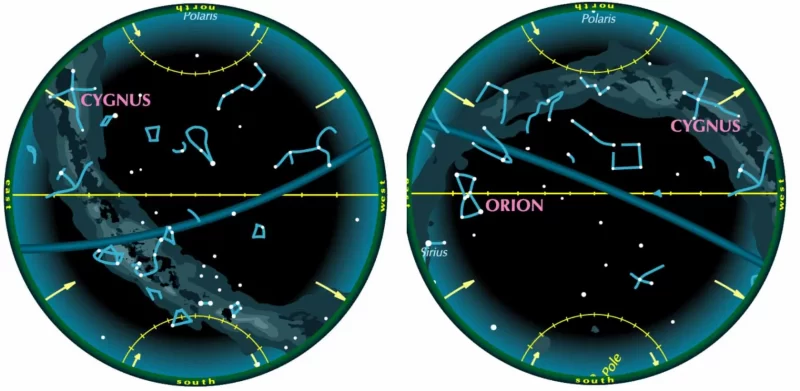

But consider the view from a different latitude – for instance, from latitude 0, the Earth’s equator.

The Swan now has its axis neither horizontal nor vertical but at about 45° to the horizon, with its head (Albireo) leading – upper when rising, lower when setting.

And consider Orion, a constellation that straddles the celestial equator.

Its axis is north-south, so it’s parallel to the horizon whether rising or setting – no surprise.

How is the orientation of a constellation determined?

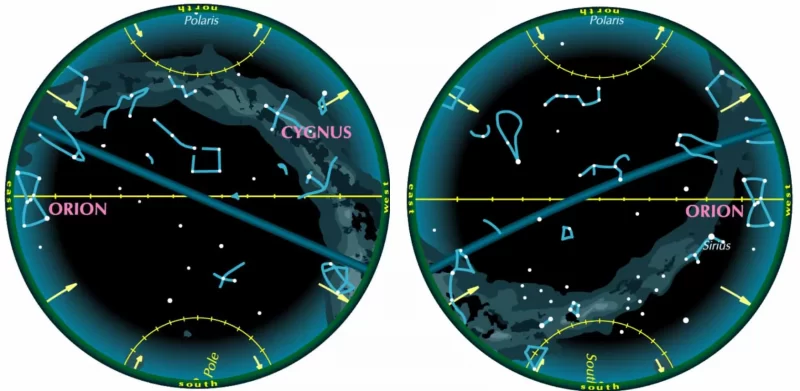

What determines a constellation’s attitude at a given time – the relation of its axis to the horizon – is the angle between the axis and the line to the north celestial pole.

In the case of Orion, that angle is zero: the axis points due north. So Orion’s attitude is the same whether rising or setting. (Actually we should say it is complementary: for places at latitudes other than the equator, it slopes; the slope when rising is the same as that for setting, but in the opposite direction.)

In the case of Cygnus, its axis does not point at Polaris but roughly 45° to the east of it. So that angle is subtracted from the axis’s slope when rising, and added to it when setting. Thus making it 0°, and 90°.

So, it’s all spherical trigonometry, the algebra of angles between curves on a sphere, the celestial sphere. In fact, it’s something we can understand and solve only laboriously, but which – as with so much about the sensory world – our eyes solve instantly without knowing what they are doing.

Bottom line: Guy Ottewell answers the question: Since Cygnus is vertical as it sets in the west, why is it not also vertical as it rises in the east? The answer is not obvious or quick.