The video above – from Greg Hogan of Kathleen, Georgia – shows the fast movement over 28 minutes of green Comet 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdušáková – which swept closest to Earth on February 11, 2017, temporarily becoming the most famous comet that practically nobody saw. Its closest point was around 8 UTC on Saturday, at which time the comet was 0.08 AU (7.4 million miles, about 12 million km, or some 30 times the moon’s distance) from the Earth. Experienced observers and astrophotographers, used to finding faint objects in the sky, had a shot at seeing it, although they had to contend with this weekend’s bright moon. The estimated brightness of Comet 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdušáková at its closest and brightest was magnitude +7. That’s well outside the limit for visibility with the unaided eye. What’s more, a diffuse object, like a comet, is even tougher to see at that magnitude, or any magnitude. The comet is still around, but an extremely dark sky and optical aid (at least binoculars, probably a telescope) are needed to see it.

On the other hand, we are beginning to see a few photographs of Comet 45P, and we’re hoping we’ll see more in the days ahead.

Brian Ottum, who created the beautiful composite image above on February 7 with three 5-minute exposures and a 10-inch telescope, told EarthSky:

I’ve been taking shots of 45P for 2 months. Waited excitedly for it to emerge from the sun’s glow. Unfortunately, it seems to be fading. No naked eye comet here.

Abhinav Prakash Dubey in New Delhi, India caught the green comet on February 7, too. His image, below, gives you a better idea of how some faint comets look on the sky’s dome, but his image is a composite, too (5 frames, 2-mins each stacked in Photoshop). Notice how many stars are visible here; your eye doesn’t see this many. Still, it’s a gorgeous photo. The comet is the blurry spot, around 8 o’clock from center.

Chris Plonski in Charlotte, North Caroline wrote that he had:

… poor transparency and poor seeing, high altitude clouds swirling, gusting winds and a full moon.

But, still, Chris managed to catch 8 frames at ISO 3200 4-minute consecutive exposures (32 minutes total) showing the speed of the comet’s movement.

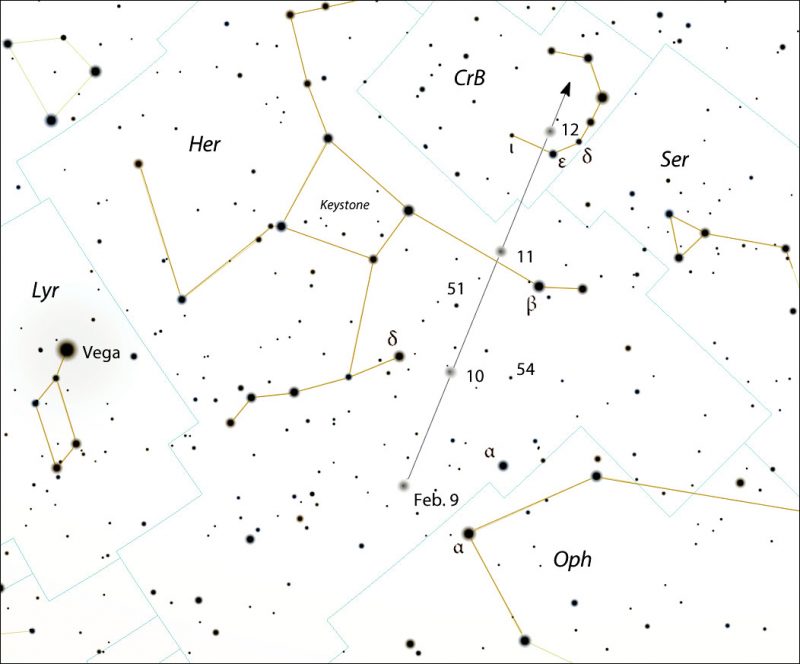

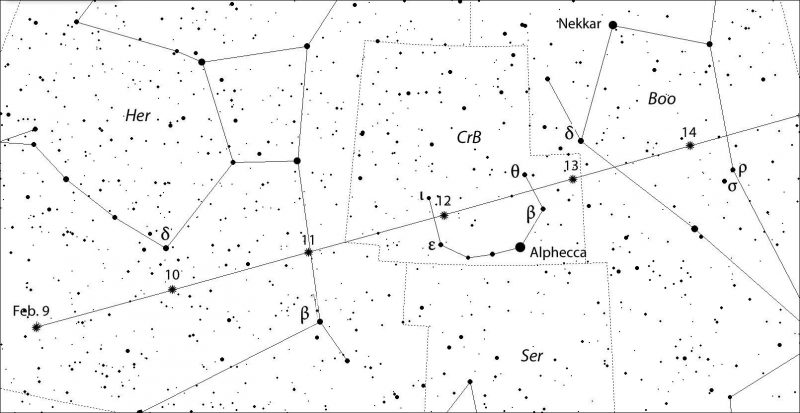

If you want to give the comet a try in the days ahead – especially if you’re a photographer or experienced skywatcher – we have some charts you can use, below, courtesy of Bob King aka AstroBob. The comet is in the sky before dawn, about 82 degrees west of the sun at maximum brightness. As you can see from the photos on this page, some people are catching it. But, as Bob King points out in his article at skyandtelescope.com:

Guess who’s back throwing unshielded light around with abandon? Yep! Starting Thursday (February 9), the waxing gibbous moon pushes into the morning sky and remains there as the comet whirls west and slowly fades.

The comet will be fading as it passes through the constellations Corona Borealis, Boötes, Canes Venatici, Ursa Major into Leo by the end of February.

This comet passed closest to the sun that binds it (and us) in orbit on December 31, 2016. It’ll soon recede back into the deeper space of our solar system, but it’ll always return, as least for the foreseeable future. Its orbital period is only 5.25 years. At its 2011 return near the sun, Comet 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdušáková made a slightly closer pass to Earth. Many observers saw it with binoculars that year. Maybe those 2011 observations are helping to prompt media attention this year, which is why so many people are asking.

By the way, we didn’t see very many astrophotos of the comet’s much-publicized sweep near the moon on New Year’s Eve, 2016. But at least one Japanese astrophotographer (@w_coast) got a gorgeous shot of the moon and comet on January 1, which he posted to Twitter (and a shout-out to @cosmos4u on Twitter for pointing it out).

???45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdusakova (2016)

5?? ISO800 300mm 2.8 10sec.×ave.53 pic.twitter.com/23qEl1Q6BD— ???? (@w_coast) January 1, 2017

Bottom line: Green Comet 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdušáková passed closest to Earth on February 11, 2017. It is not particularly close, and it’s not bright enough to see with the eye. It’s not even an easy object with binoculars. But astrophotographers might catch it! If you do, submit your image to EarthSky here.