The moon is just a few days past full on the nights of April 21 and 22. Meanwhile, the Lyrid meteor shower is expected to put forth its greatest number of meteors during the predawn hours on April 22 and especially April 23. If you’re a veteran meteor-watcher, you’re already shaking your fist at the moon. Its glare will drown out all but the brightest Lyrids. However, the moon offers its own delights, sweeping past Jupiter – the largest planet in our solar system and second-brightest planet in our skies – on these mornings. Also, you can look for the bright star Vega, which nearly marks the radiant point of the Lyrid meteor shower. Both Jupiter and Vega should have no trouble overcoming the moon-drenched skies. Find them, enjoy them … and maybe you’ll spot a meteor, too!

By the mornings of April 24 and 25, the moon will have passed Jupiter to appear near Saturn.

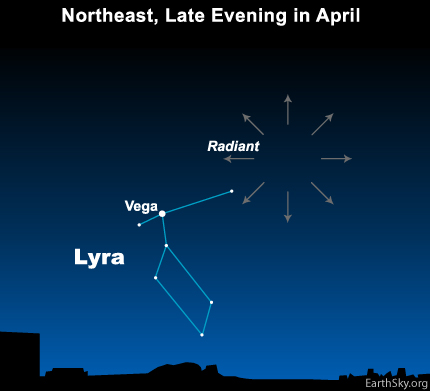

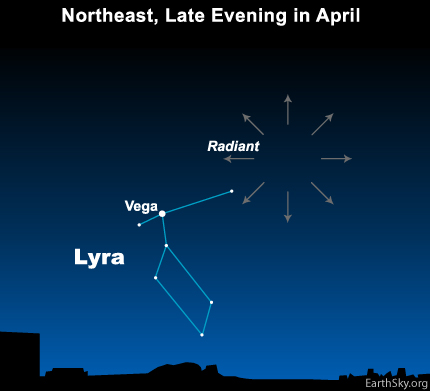

The greatest number of Lyrid meteors usually falls in the few hours before dawn. That’s when the radiant point – near the star Vega in the constellation Lyra – is highest in the sky. For that reason, that’s when you’re likely to see the most meteors, albeit, this year, in the light of the moon.

Note for Southern Hemisphere observers: Because this shower’s radiant point is so far north on the sky’s dome, you’ll see fewer Lyrid meteors. But you might see some! If you want to watch, try the moonlit skies between midnight and dawn on April 22 and/or 23.

On a dark night, this shower typically offers about 10 to 15 meteors per hour at its peak. Unfortunately, in 2019, the moon is sure to bleach out a good number of Lyrid meteors. That is, the meteors will be flying. If you’re out watching, you might notice a few. Hopefully, a few of the brighter ones will prevail over the moonlight.

Want to watch the shower in moonlight? Click here for tips on watching 2019’s Lyrid meteor shower

2019 is also a good year to see the Lyrid meteor shower’s radiant point, just to the right of beautiful blue-white Vega, the brightest light in the constellation Lyra the Harp. Vega is bright enough to be visible from some light-polluted cities. It’s bright enough to be visible in moonlight. What’s a radiant point? If you trace the paths of these Lyrid meteors backward on the sky’s dome, you’ll find that they appear to originate from near Vega, which is the heavens’ fifth brightest star.

It’s from Vega’s constellation Lyra that the Lyrid meteor shower takes its name.

You don’t need to identify a shower’s radiant point in order to watch a meteor shower. The meteors radiate from this point, but they appear unexpectedly, in any and all parts of the sky.

However, knowing the rising time of a radiant point helps you know when the shower is best in your sky. Assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, Vega rises above your local horizon – in the northeast – around 9 to 10 p.m. local time. It climbs upward through the night.

The higher Vega climbs into the sky, the more meteors you’re likely to see. By midnight, Vega is high enough in the sky that meteors radiating from her direction streak across your sky. Just before dawn, Vega and the radiant point shine up high, and the meteors will be raining down from the top of the sky (assuming you’re in the Northern Hemisphere).

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Why do the meteors radiate from a single part of the sky? The radiant point of a meteor shower marks the direction in space – as viewed from Earth – where Earth’s orbit intersects the orbit of a comet. In the case of the Lyrids, the comet is comet Thatcher. This comet is considered the “parent” of the Lyrid meteors. Like all comets, it’s a fragile icy body that litters its orbit with debris. When the bits of debris enter Earth’s atmosphere, they spread out a bit before they grow hot enough (due to friction with the air) to be seen. So meteors in annual showers are typically seen over a wide area centered on the radiant, but not precisely at the radiant.

Only 10 to 15 meteors per hour doesn’t sound like many. But even an hour under a still, dark sky – raining down a dozen or so meteors – is a treat. Plus, the April Lyrids can surprise you. They’re known to have outburts of several times the usual number – perhaps up to 60 an hour or so – on rare occasions. Meteor outbursts aren’t always predictable. So – like a fisherman – you’ll want your lawn chair, a thermos of something to drink, whatever other gear you feel you need – and then you need to wait. Not a bad gig.

Bottom line: That bright moon in the sky before sunup will drown most of the ongoing Lyrid meteor shower from view. But the moon offers its own delights, sweeping past Jupiter in the next few mornings. In 2019, the peak numbers of Lyrid meteors are expected to produce the greatest numbers before dawn April 23, though in moonlit skies.