A large, systematic study of world-wide shark and ray populations reveals that about 25 percent could go extinct within the next few decades. The reason: overfishing. The Shark Specialist Group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) published a paper describing the dire global status of cartilaginous fish – including sharks and rays – on January 21, 2014 in the journal eLife.

Nick Dulvy of Simon Fraser University in Canada – chair of the IUCN’s Shark Specialist Group – said in a press release:

There are no real sanctuaries for sharks where they are safe from overfishing.

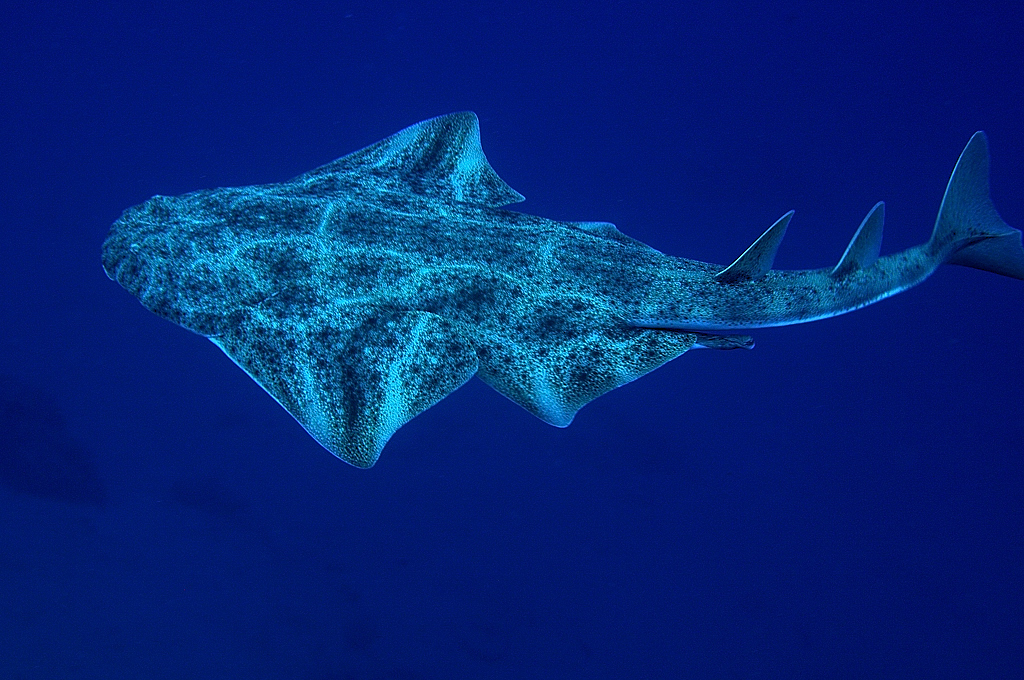

In the most peril are the largest species of rays and sharks, especially those living in relatively shallow water that is accessible to fisheries. The combined effects of overexploitation—especially for the lucrative shark fin soup market—and habitat degradation are most severe for the 90 species found in freshwater.

A whole bunch of wildly charismatic species are at risk. Rays, including the majestic manta and devil rays, are generally worse off than sharks. Unless binding commitments to protect these fish are made now, there is a real risk that our grandchildren won’t see sharks and rays in the wild.

Overfishing of shark and ray species has been well-documented at the regional level.

However, this new study, the product of two decades of 17 workshops involving 300 experts, surveyed the status of these species at a global level. Scientists studied all available information about cartilaginous fish — sharks, rays, and chimaeras — such as their distribution, population trends, fishing harvests, threats, and efforts in conservation.

They found that 249 out of 1041 known species of cartilaginous fish fall under the “Critically Endangered,” “Endangered,” and “Vulnerable” categories in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Included in the “Threatened” lists were 107 species of rays and skates, and 74 species of sharks. Compared to other types of animals, sharks and rays face a much higher extinction rate. They also have the lowest percentage of species deemed “of least concern,” just 23 percent.

The main sites subjected to severe over-fishing were the Indo-Pacific, particularly the Gulf of Thailand, as well as the Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea.

Losing sharks and rays, says Dulvy, will be like losing whole chapters of our evolutionary history.

They are the only living representatives of the first lineage to have jaws, brains, placentas and the modern immune system of vertebrates.

And losing them, he added, is frightening for many reasons.

The biggest species tend to have the greatest predatory role. The loss of top or apex predators cascades throughout marine ecosystems.

The IUCN Shark Specialist Group is urging governments to put more protective measures in place for sharks, rays and chimaeras, such as banning the capture of the most threatened species, fishing quotas based on scientific analysis of fish populations, protecting important habitats, and enforcement of protective measures.

For additional images, please visit the Dulvy Lab page.

Bottom line: Twenty-five percent of shark and ray species could be extinct within the next few decades. That’s the conclusion of a systematic study of world-wide cartilaginous fish populations, recently published in the journal eLife by the Shark Specialist Group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Scientists found that sharks and ray had a higher extinction rate compared to other types of animals, with 107 species of rays and skates, and 74 species of sharks labeled as “threatened.”