The Texas Gulf coast is among the most dynamic environments on Earth. Along the upper Texas coast, the shoreline is retreating at about 1.6 meters each year. Relative sea-level rise, local circulation patterns, high intensity storms and lack of sediment supply combined with human activities along developed areas of the barrier island all might have contributed to this chronic erosion, although the relative significance of each is still largely unquantified. Research scientist Jeffrey Paine of the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas talked to EarthSky about how scientists study one of the most important coastlines on the planet, and about the risks and value of human activity there.

You’ve written that in some places along the Texas Gulf Coast, the shoreline is retreating by 1.6 meters each year. Tell us more about that, and how that compares to other coastlines on this planet.

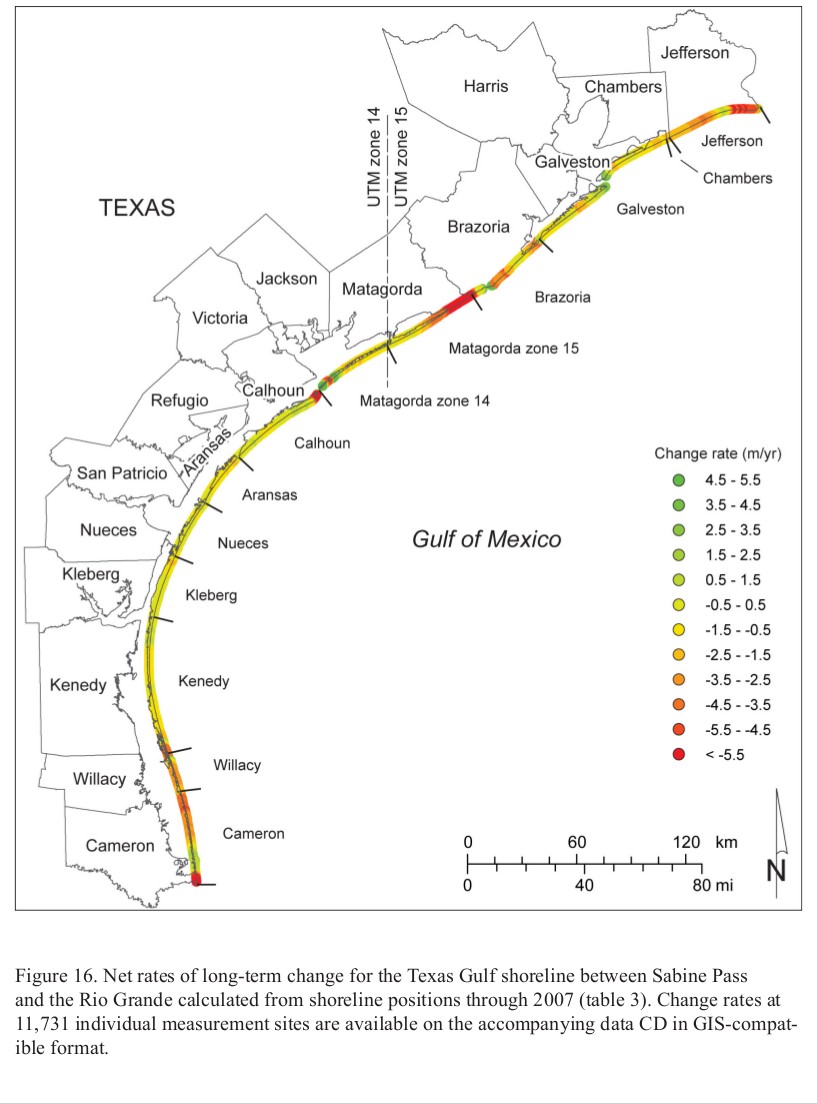

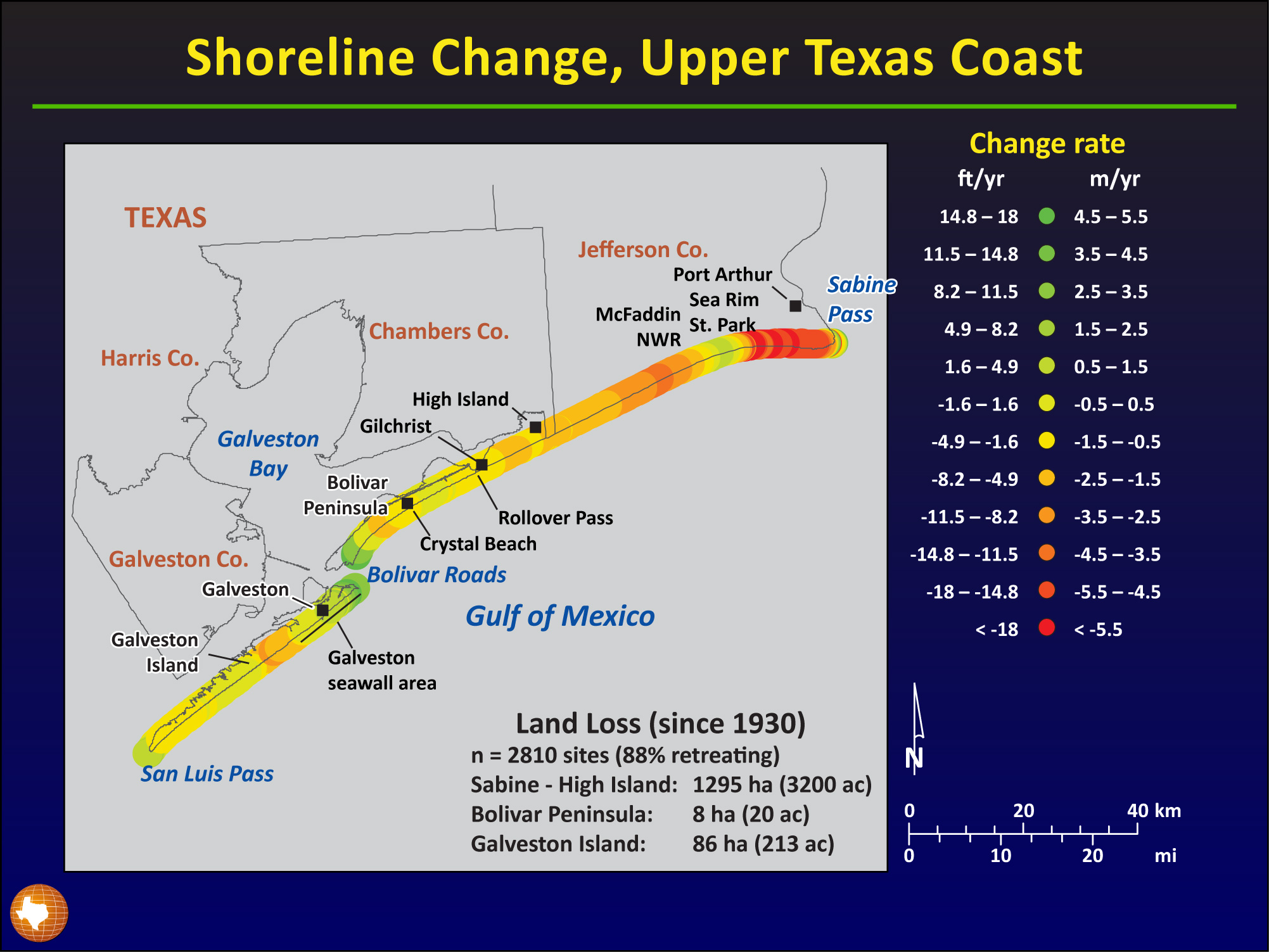

We derive that number from studies here at the bureau that began in the 1970s. That number actually is an average rate for the upper Texas coast, the part of the Texas coast that’s eroding most rapidly. For the Texas coast as a whole that average rate is about 1.2 meters per year. And for the lower coast it’s about one meter per year. That’s among the most rapid rates of shoreline retreat in the United States. You’ll find more rapid rates in places such as Louisiana and Mississippi, and lower rates in such places as the West Coast, the Northeastern Coast and Florida.

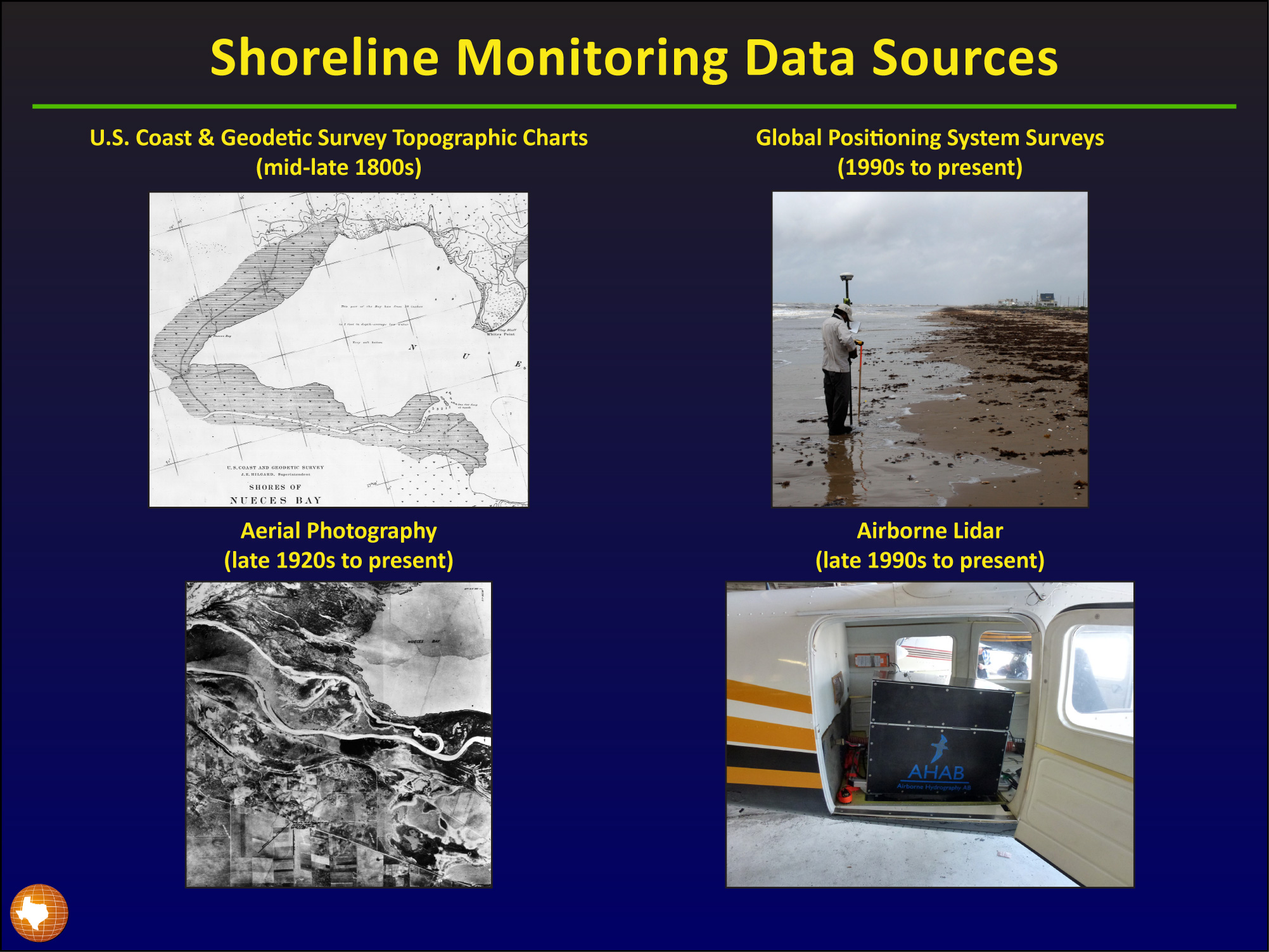

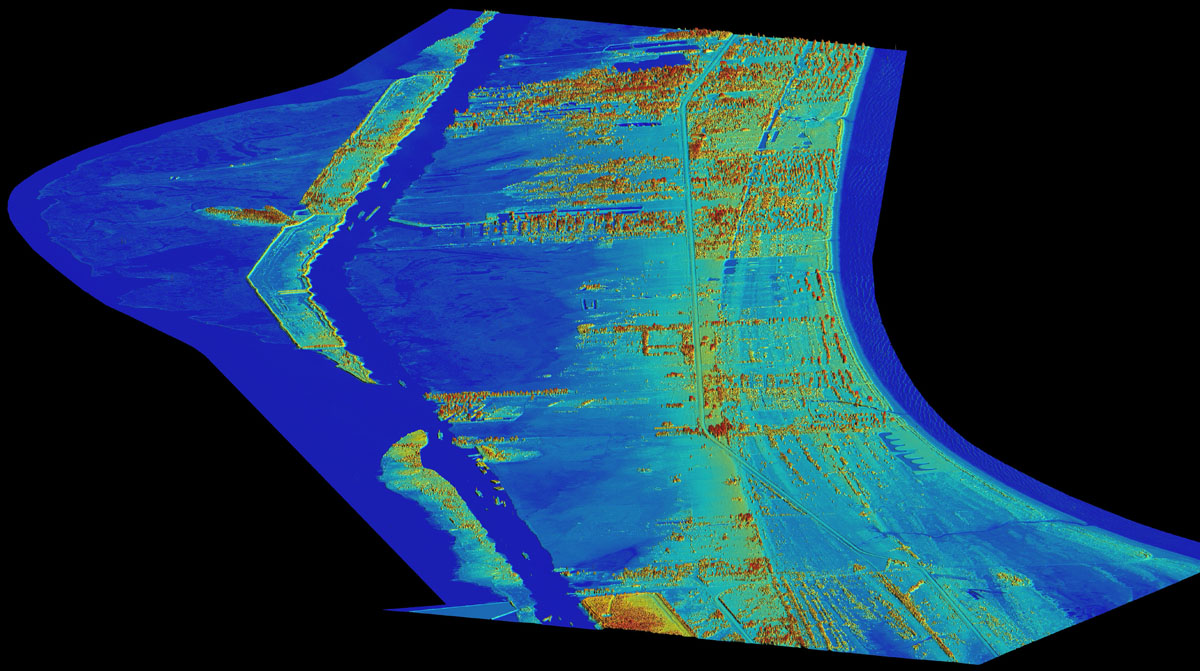

The kinds of materials we’ve used to determine those rates include topographic charts painstakingly made by the U.S. Coast in Geodetic Survey in the late 1800s using boats, and aerial photographs that began on the coast around 1930, to much more recent and modern techniques including global positioning system satellites and receivers and even an airborne laser based systems for mapping swaths of the shoreline remotely. All those things have enabled us to determine past shoreline positions relatively accurately. We compare those positions over time to determine the long-term rates of shoreline change.

What causes the Texas coastline to change? I understand it’s a combination of natural and human factors that’s led to what some scientists describe as a dramatic shoreline retreat on the Texas Gulf Coast. What’s known about the causes?

Most of us assume that the environment that we’re in is going to be stable over time. But anyone whose been to a beach knows that the beach is a dynamic environment that changes from hour to hour and day to day with tidal cycles and wave energy and wind and storms and all of those features.

In a broader context, the shorelines along the Texas coast have been retreating for most of the last 20,000 years during the last glacial-interglacial cycle. The peak of the last glaciation was about 20,000 years ago. Sea level was approximately 100 to 120 meters lower than it is today and the shorelines were out near the edge of the continental shelf.

As that glaciation ended and all those glaciers and ice sheets melted, lots of water was dumped into the oceans and the sea level rose rapidly until about 5,000 years ago, and then much slower during the last 5,000 years. So most of the shorelines along the Texas coast and the Gulf of Mexico have been eroding naturally for the last 10 to 20,000 years.

Much of the Texas coastal plain is composed of unconsolidated sediments. What I mean by unconsolidated sediments is that sediments that are made of sand and silts and clays that have not been hardened into a rock. They are something that you could dig up or pull apart with a shovel or a rake. They’re not lithified like a granite or a sandstone or a shale would be. They’re on their way to being that, but they’re not there yet. And unconsolidated sediments on the shore are attacked by the waves that are generated by winds. The wave action on the coast is augmented by each day’s tidal cycle that creates the erosion potential that causes the beaches to retreat.

There are also storms that affect the coast. We have an average of something like four tropical storms and four hurricanes per decade that create elevated tides and strong wind-driven waves. Storm ‘surge’ and waves attack the shorelines and move a tremendous amount of sediment around. Some of it then it leaves the system and is not available for the beach to recover once the storm has passed. These sediments are going off into deeper water or being deposited on land as wash over deposits.

We also have sea level rise. Global average rates of sea level rise for the last century are anywhere from 1 to about 3 millimeters per year. What that does on the Texas coast is it causes submergence of low lying marshes and tidal flats. It also brings wave energy up higher on the beach, increasing the erosion potential.

So we have global sea level rise, but we also have a contributing factor on the Texas coast, called subsidence, which is a natural compaction of unconsolidated sediments that are underneath us. Subsidence can be accelerated by removal of fluids – either ground water withdrawal or oil and gas production in areas where we have beaches. Land subsidence leads to what’s effectively a higher rate of relative sea level rise – that is, the rates sea level would rise relative to the local land surface can be higher than the globally averaged rates of sea-level rise.

Tell us your impressions about what’s really happening with these causes behind this dramatic retreat of the Texas shoreline.

The potential causes of the subsidence that we see on the Texas coast include natural compaction. We know that those sediments are unconsolidated and they can compact under their own weight. And therefore the ground surface can sink.

Other causes that have been mentioned by other researchers include ground water withdrawal, where you pump water from the ground. Water moves from clay particles into sandy reservoirs and then the clay compacts, causing a net thinning of the strata above the area where the water is being produced.

Production from relatively shallow oil and gas reservoirs can also contribute to subsidence. Those reservoirs are under pressure when they’re being produced and that pressure declines over time. Some of that pressure may have helped hold up the sediments above them. Some people have theorized that when that pressure declines, there’s a net sinking of the land above those oil and gas reservoirs.

What would you like to say to someone who is concerned about the retreating shoreline along the Texas coast. And also maybe you could talk about long-term solutions.

Shoreline retreat has been a long standing natural process. Shoreline retreat is a threat to us only because we have built structures and are living on the coast in greater and greater numbers. If we weren’t there, there really would be no great threats to us from shoreline retreat. But once someone builds a home or a business on the low land along the Texas coast they are at risk from storm surge and from long-term shoreline retreat. There are many examples of homes that were built in an aesthetically desirable location on the first row landward of the beach. Many of these homes were on the beach itself within years to decades as a result of shoreline retreat and erosion during storms. In Texas, the Open Beaches Act protects public access to the beach. So when structures get out on the beach then something needs to be done, because then they are restricting the public access to that beach.

Shoreline retreat also serves as a ‘canary in the mine’ for monitoring global climate change. Retreat rates are influenced by sea-level rise, and that of course is related to global warming, regardless of the cause, whether you believe it’s natural or human-induced. It’s certainly a fact that sea level is rising, and that rise affects shoreline change rates along the Texas coast. So we can indirectly look at climate change and sea-level rise by monitoring shoreline position.

For those who are concerned about shoreline retreat, there aren’t too many practical options for mitigating the effects of shoreline erosion. In some areas, the city of Galveston for example, we’ve made a decision as a general public to preserve what’s there, and supported the construction of engineered structures like the Galveston sea wall.

But in places where fewer people live and where there’s not such an economic impact related to shoreline retreat, your options for dealing with retreat are limited. They include moving. They can include nourishing the beaches by adding sand or artificially building up the land surface. We have a shortage of sediments on the Texas coast that’s been caused by damming of rivers and construction of jetties and ship channels that trap sediment, which has led to local and perhaps regional increases in rates of shoreline retreat.

And so engineered structures can help us ameliorate the effects of shoreline retreat. But there’s not only the cost of constructing them, there’s also the cost of maintaining them in the future. For a shoreline that’s as long as ours with more than 300 miles of shoreline, an engineered solution would be prohibitively expensive.

If I were someone who were considering building a structure on the coast, and concerned about its long-term viability, I would look at some of the data sources that are out there for determining what the long-term rates of change are. Some areas of the coast are relatively stable. Others are retreating at highly rapid rates, sometimes as much as 15 meters per year or more. So location is important. But all of those places on the coast would be susceptible to hazards such as hurricanes, tropical storms, and storm surge. So it should be no surprise that there truly is no absolutely safe place to build on the Texas Gulf shoreline.

Would you tell us about the barrier islands that line the Gulf of Mexico shoreline? What’s important to know?

The barrier islands on the Texas coast are considered to be the first line of a defense for inland areas from surge associated with tropical storms and hurricanes, largely because they’re big sandy features that have well-developed dunes behind the beach. In some cases those dunes are the highest point for miles around. They are a natural sea wall for the areas behind the dunes.

The dunes aren’t well-developed along the entire coast. Areas like the upper Texas coast don’t necessarily have well developed dunes, partly because of a lack of sediment supply, partly because of long-term erosion, and partly because of the impacts of recent storms in those areas. The dunes are always damaged by major storms and they take a while to recover. For example, Hurricane Ike struck the upper Texas coast in 2008. It was only a Category 2 storm, but it was a huge storm. It caused a tremendous amount of beach and dune and coastal damage along the upper Texas coast. That part of the coast is still recovering from Ike and some areas will never fully recover.

What’s the most important thing you want people today to know about changes happening to the Texas Gulf coast?

We live on a very dynamic coast here in Texas, and everywhere really around the Northern Gulf of Mexico. It’s an environment that’s naturally dynamic and has been that way for as long we can look into the past. It’s a zone that changes greatly over time and most of us are not used to that. We go to an area and we have our piece of land surveyed and we expect it’s going to stay there for our lifetime and many lifetimes to come.

That’s not the case on the Texas coast. You can survey an area, but waves and sea level rise and storms don’t really pay much attention to where survey markers are. Many people on the coast have learned the difficult lesson that what you build there may not last forever. I think the big lesson really in studying shoreline change over time is that it’s a demonstration of how dynamic that the coastal zone is, and will continue to be.