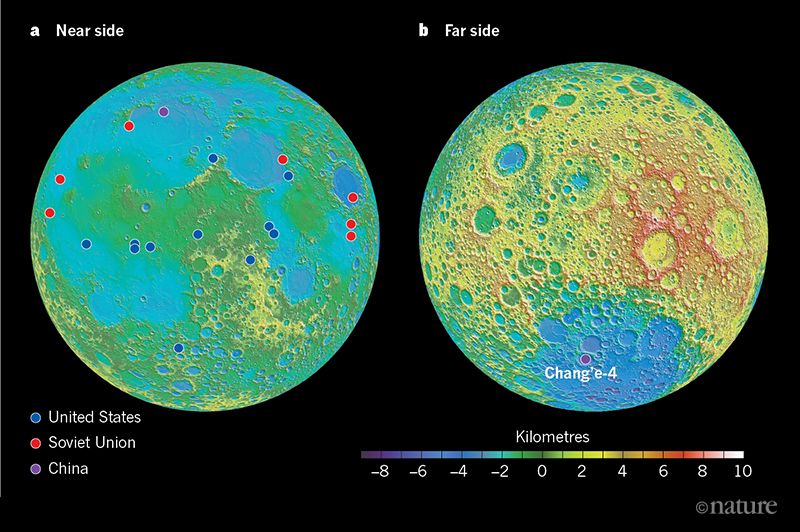

On January 3, 2019, a Chinese spacecraft called Chang’e 4 became the first-ever mission to land on the moon’s far side. It set down in a giant impact feature on the moon, called the South Pole-Aitken Basin, within a smaller and newer impact crater, called Von Kármán. Last week (May 15, 2019), Chinese scientists published early scientific results from the Chang’e 4 mission, after collecting the first in situ data from the crater floor. These scientists report the detection of materials near Chang’e 4 landing site that they said “differ markedly” from most samples from the moon’s surface. They said they believe it’s possible this material came from deeper within the moon, from the moon’s mantle, which is known to be a geologically distinct layer from the moon’s crust and core. The detection of mantle material on the moon’s far side was a major goal of the Chang’e 4 mission. The work – which sheds light on how the moon evolved – was published on May 15, 2019 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature.

In a way similar to other worlds in the inner solar system, the moon is thought to have gone through a phase – not long after its formation – when an ocean of magma or molten rock covered its surface. A statement from the Chinese Academy of Sciences explained:

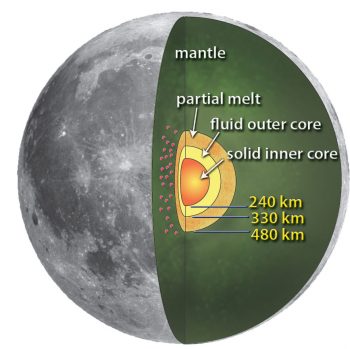

As the molten ocean began to calm and cool, lighter minerals floated to the top, while heavier components sank. The top crusted over in a sheet of mare basalt, encasing a mantle of dense minerals, such as olivine and pyroxene.

Thus the moon ended up with compositionally distinct layers in its interior. Materials from the moon’s mantle likely found their way to the surface when space rocks (what we call asteroids) crashed into the moon’s surface; the impacts cracked the moon’s crust and kicked up pieces of its mantle, these scientists explained. Li Chunlai of the National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences – commander-in-chief of the ground application system of Chang’e 4 – was lead author of the new paper. He said:

Understanding the composition of the lunar mantle is critical for testing whether a magma ocean ever existed, as postulated. It also helps advance our understanding of the thermal [heat] and magmatic [molten rock] evolution of the moon.

These scientists also pointed out that the evolution of the moon “might provide a window” into the evolution of Earth and other terrestrial planets. That’s because the moon has no atmosphere or weather, no wind or water erosion. Its surface is relatively untouched and more like the early planetary surface of Earth.

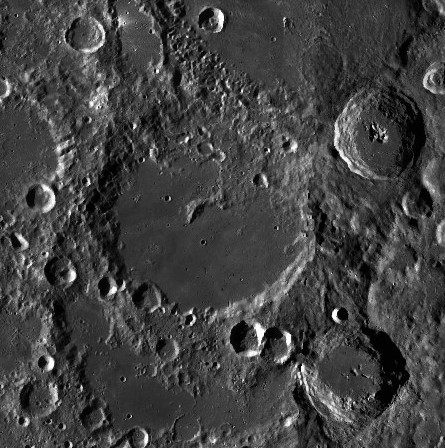

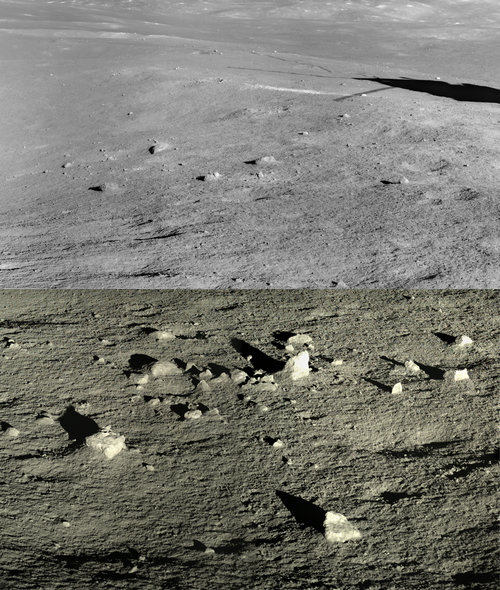

The South Pole-Aitken Basin on the moon is vast, stretching about 1,500 miles (2,500 km). It’s also an impact feature, one of the largest known in the solar system. It’s the oldest and largest structure known on the moon. Li and his team landed Chang’e 4 there, within the Von Kármán crater, a smaller and younger crater, created in a more recent impact event. They released a lunar rover, called Yutu2. Their findings are based on the spectra (rainbow colors) of reflected light, recorded by Yutu2 as it traversed the Von Kármán crater. They expected to find mantle material there, since the original impact event that created the basin would have penetrated well into and past the lunar crust.

What they did find mystified them. Yutu2 travels across the crater revealed only traces of olivine, which is the main ingredient in Earth’s upper mantle. Li said:

The absence of abundant olivine in the South Pole-Aitken Basin interior remains a conundrum. Could the predictions of an olivine-rich lunar mantle be incorrect?

However, as it turned out, more olivine appeared in the samples from deeper impacts. One theory, according to Li, is that the mantle consists of equal parts olivine and pyroxene – another ingredient in Earth’s upper mantle – rather than being dominated by one over the other.

Chang’e 4 is still on the moon, still operating. Its mission is planned for 12 months, so, if all goes as planned, it will operate through the end of 2019. These scientists said the mission:

… will need to explore more to better understand the geology of its landing site, as well as collect much more spectral data to validate its initial findings and to fully understand the composition of the lunar mantle.

The Chinese Lunar Exploration Program has been steadily moving toward lunar exploration for some time. China first reached lunar orbit with Chang’e 1 in 2007 and Chang’e 2 in 2010. It landed Chang’e 3 on the moon and released a rover in 2013. Chang’e 4 is now on the moon’s far side, a historic achievement. The stated goal of China’s moon program includes the collection of samples with future missions, Chang’e 5 and Chang’e 6. Ultimately, China has said, it wants to land humans on the moon by the 2030s and possibly build an outpost near the moon’s south pole.

Like its predecessors, the Chang’e 4 mission is named for Chang’e, the Chinese moon goddess.

Bottom line: Chinese scientists have released the first scientific results from the Chang’e 4 mission on the moon’s far side. They data from the Yutu2 rover to identify lunar mantle materials on the moon’s surface.

Source: Chang’E-4 initial spectroscopic identification of lunar far-side mantle-derived materials