Tiny swimming robots seeking life

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in southern California said this week (June 28, 2022) that one of its scientists – robotics mechanical engineer Ethan Schaler – has received a Phase II award to continuing developing a swarm of tiny robots. These robots would be capable of seeking alien life. These wouldn’t be rovers, however. Instead, they’d be swimmers, designed to explore some of the most promising ocean worlds in our solar system.

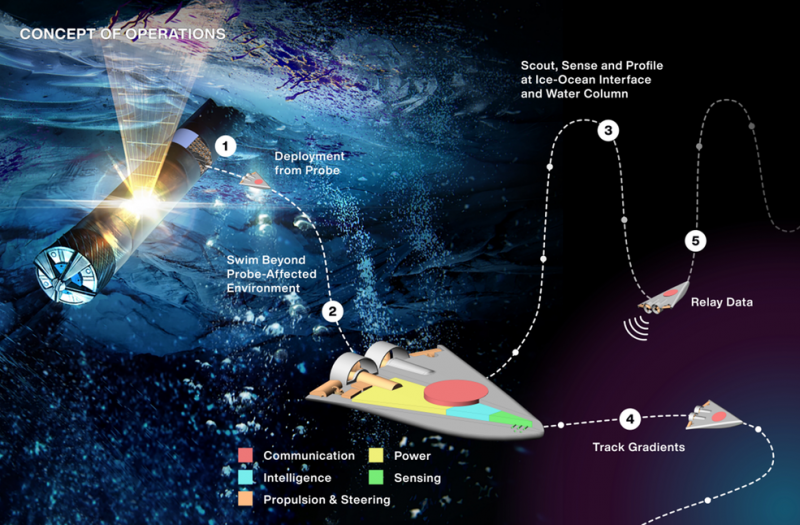

The idea is to send the swimming bots to Jupiter’s moon Europa, or Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Significantly, both are thought to have liquid oceans below icy crusts. About four dozen cellphone-sized bots could fit into a narrow ice-penetrating probe known as a cryobot. Then, once at Europa, or Enceladus, the cryobot would bore into the moon’s crust, to the ocean below.

Subsequently, the cryobot would then release its bots into the alien sea. The little swimmers would roam those seas, far from their mothership, seeking and measuring the seas’ properties. They’d be analyzing the suitability of these distant oceans for life as we know it. For instance, they’d seek biomarkers, telltale signals indicating the ongoing presence of life.

A new NASA award lets the concept move foward

Presently, Schaler’s concept is called SWIM, for Sensing With Independent Micro-Swimmers. The NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program has awarded it with $600,000 in Phase II funding. The new funds follow a 2021 award of $125,000 in Phase I NIAC funding to study feasibility and design options. Ultimately, that will allow him and his team to make and test 3D-printed prototypes over the next two years. A statement described Schaler’s SWIM concept:

…The early-stage SWIM concept envisions wedge-shaped robots, each about 5 inches (12 cm) long and about 3 to 5 cubic inches (60 to 75 cubic cm) in volume. About four dozen of them could fit in a 4-inch-long (10-cm-long) section of a cryobot 10 inches (25 cm) in diameter, taking up just about 15% of the science payload volume.

That would leave plenty of room for more powerful but less mobile science instruments that could gather data during the long journey through the ice and provide stationary measurements in the ocean.

What’s next for tiny swimming robots?

The SWIM concept isn’t yet part of any NASA mission. But, even so, scientists have long felt the lure of Jupiter’s moon Europa. Indeed, a new mission – called Europa Clipper – is planned for a 2024 launch. NASA said earlier this month that the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland has now delivered the main body of Europa Clipper to JPL in Pasadena, California. Over the next two years, the rest of the spacecraft will be assembled at JPL. Europa Clipper will launch in October 2024 and arrive at Jupiter in 2030. NASA said Europa Clipper:

… will begin gathering detailed science during multiple flybys with a large suite of instruments when it arrives at the Jovian moon in 2030. Looking further into the future, cryobot concepts to investigate such ocean worlds are being developed through NASA’s Scientific Exploration Subsurface Access Mechanism for Europa (SESAME) program, as well as through other NASA technology development programs.

Read more about Europa Clipper

Why SWIM?

NASA said SWIM’s intent would be:

… to reduce risk while enhancing science. The cryobot would be connected via a communications tether to the surface-based lander, which would in turn be the point of contact with mission controllers on Earth. That tethered approach, along with limited space to include large propulsion system, means the cryobot would likely be unable to venture much beyond the point where ice meets ocean.

SWIM team scientist Samuel Howell of JPL, who also works on Europa Clipper, commented in the NASA statement:

What if, after all those years it took to get into an ocean, you come through the ice shell in the wrong place? What if there’s signs of life over there but not where you entered the ocean? By bringing these swarms of robots with us, we’d be able to look ‘over there’ to explore much more of our environment than a single cryobot would allow.

Howell compared the concept to NASA’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter. Ingenuity is the airborne companion to the agency’s Perseverance rover on the Red Planet. He said:

The helicopter extends the reach of the rover, and the images it is sending back are context to help the rover understand how to explore its environment. If instead of one helicopter you had a bunch, you would know a lot more about your environment. That’s the idea behind SWIM.

Bottom line: Tiny swimming robots sound like cool science fiction. But a JPL robotics engineer is developing them, for future missions to ocean worlds like Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.