A comment by SpaceX president and COO Gwynne Shotwell has sparked interest in whether SpaceX’s Starship spacecraft might be useful in helping to clean up space debris orbiting Earth … when it’s not busy taking humans to the moon and Mars. Shotwell inserted a comment about Starship’s role as a potential space-age garbage collector during an online interview with Time magazine (Time 100 Talks) released on October 22, 2020.

In the video above, Shotwell’s comment about Starship’s possible part-time job as a space-age garbage truck begins at about the 8-minute mark. Shotwell was giving a nod to Starship’s planned reusability, which will allow the entire spacecraft to launch back and forth from Earth orbit to Mars repeatedly, when she said:

I do want to put in a plug for Starship here … Starship also has the capability of taking cargo and crew at the same time. And so it’s quite possible that we could leverage Starship to go to some of some of these dead rocket bodies – other people’s rockets, of course – basically, go pick up some of this junk in outer space.

It’s not going to be easy, but I do believe that Starship offers the possibility of going and doing that. And I’m really excited about it.

Starship is at the heart of SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk‘s longtime Mars-colonization goal, which he has said may likely be the private company’s primary vehicle for future space travel. If all goes according to plan, Starship’s many tasks will include launching people to the moon, Mars and beyond, as well as superfast travels here on Earth, carrying satellites into orbit and – perhaps – collecting and de-orbiting particularly big and troublesome pieces of space junk.

Many experts believe that space junk poses a serious threat to humanity’s use and exploration of the final frontier going forward. About 34,000 objects greater than 4 inches (10 cm) in diameter are thought to be circling Earth at this very moment, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). And it’s much harder to get an idea about the smaller stuff, but the ESA estimates are frightening: they call for about 900,000 or so orbital objects in the 0.4-inch to 4-inch (1 to 10-cm) range and 128 million shards between 0.04 inches and 0.4 inches wide (1 mm to 1 cm).

All of this material poses a serious threat to rockets and spacecraft passing by, risking major damage to hardware and flight directories because of the high velocities involved.

The costs of building and launching satellites are dropping, meaning more of them are getting flung into space and creating traffic within Earth’s orbital space lanes. The fear is that a collision or two could spawn a space junk cascade – with collisions creating more debris, which create more collisions, and so on – generating clouds of accident-causing debris. This scenario, known as the Kessler Syndrome, has the potential to make space operations in Earth orbit increasingly difficult. This dread is what fuels the idea that the spaceflight community should therefore start taking mitigation measures now.

And, of course, there have been many orbital collisions already. For example, in February 2009 the defunct Russian military satellite Kosmos 2251 barreled into the operational communications satellite Iridium 33, spawning 1,800 pieces of trackable debris (and many others too small to spot) by the following October. Additionally, China and India have generated debris clouds on purpose, during destructive anti-satellite tests in 2007 and 2019, respectively.

SpaceX in particular is one major driver for a growing population; the company has already launched nearly 900 of its Starlink internet satellites to low Earth orbit, and has permission to launch thousands more. However, this may be the reason the company is taking proactive action on the matter. In addition to space junk sweeping, the company has also decided to lower the megaconstellation’s operational altitude, Shotwell says. SpaceX’s original plans called for first-generation Starlink satellites to fly between 684 and 823 miles high (1,100 to 1,325 km), but the shift in thinking brought them down to an altitude of 340 miles (550 km).

SpaceX’s standard operating procedure for Starlink involved de-orbiting each satellite before it dies, but flying at just 340 miles up provides a sort of failsafe: atmospheric drag will bring a defunct satellite down from that altitude, to burn up in the atmosphere, in just one to five years. Starlink satellites can also perform collision-avoiding maneuvers autonomously, using information from the U.S. Department of Defense’s debris-tracking system, according to the SpaceX Starlink page.

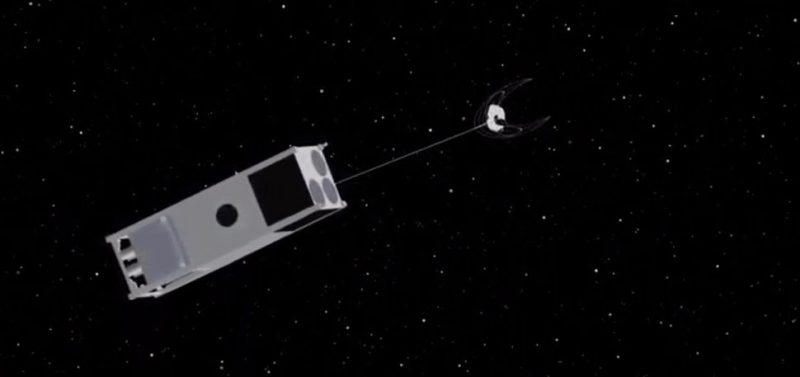

At the same time, researchers are developing a cleanup cubesat called OSCaR – an acronym for Obsolete Spacecraft Capture and Removal – which would hunt down and de-orbit debris on the cheap using onboard nets and tethers. OSCaR would do so relatively autonomously, with little guidance from controllers on the ground. The spacecraft is a 3U cubesat, meaning that it will be very capable for its small size, featuring onboard navigation and communication gear; power, propulsion and thermal-control systems; and four net-launching gun barrels. Each OSCaR satellite will be capable of capturing and removing four pieces of debris, and when that work is done, the cleanup cubesat will de-orbit itself within five years.

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute aims to test OSCaR on the ground sometime this year, and a test in space will follow at some point if all goes according to plan.

SpaceX is working toward the final Starship design via a series of increasingly ambitious prototypes.

The final Starship will have six of the company’s new Raptor engines, while the Super Heavy rocket will sport about 30 Raptors. With that said, SpaceX plans to have the rocket-spaceship duo up and running relatively soon. Starship is in the running, for instance, to land astronauts on the moon for NASA’s Artemis program, which is targeting 2024 for the first of those touchdowns; Japanese art-enthusiast Yusaku Maezawa has booked a Starship trip around the moon, with a targeted launch date of 2023.

And then of course, there’s the red planet – Mars – the ultimate destination for Starship. Shotwell predicted in the video above:

If the Starship program goes as planned, I do think people will be able to travel to Mars in 10 years.

Bottom line: SpaceX Starship’s many tasks may include launching humans into space, carrying satellites into orbit and — perhaps — removing troublesome pieces of space debris. The fear is that a collision or two could spawn a space junk cascade, generating clouds of debris that cause further accidents.

Read more from Space.com: SpaceX’s Starship may help clean up space junk

Read more from Spaceflight Now: SpaceX executive pitches Starship for space debris cleanup