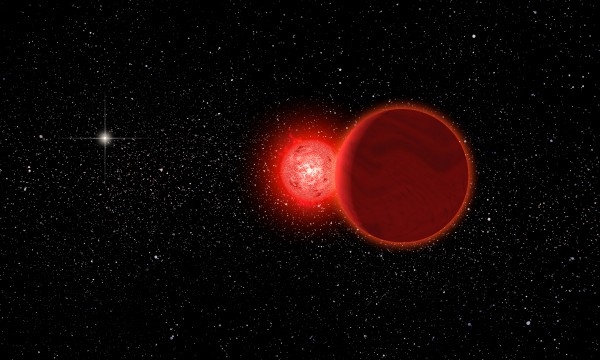

Astronomers announced this week – February 16, 2015 – that they’ve now identified the closest known flyby of a star, really two stars, to our solar system. The culprit is a binary system consisting of a low-mass red dwarf star (with a mass about 8% that of our sun) and a brown dwarf companion (with a mass about 6% that of the sun). This pair passed through our solar system’s outer Oort comet cloud some 70,000 years ago. No other star is known to have ever approached our solar system this close – five times closer than the current closest star, Proxima Centauri.

The system has the unlikely name WISE J072003.20-084651.2. It has been nicknamed Scholz’s star to honor astronomer Ralf-Dieter Scholz in Germany, who first discovered the dim nearby star in late 2013. Scholz did not then recognize its relationship to our solar system. That knowledge came more recently, from a group of astronomers from the U.S., Europe, Chile and South Africa, who determined how close the system passed to our sun, and how long ago. Astrophysical Journal Letters published this study, which was led by Eric Mamajek of the University of Rochester. The study suggests the stars passed roughly 52,000 astronomical units away (or about 0.8 light years, which equals 8 trillion kilometers, or 5 trillion miles).

Space is vast, and the stars lie at great distances from each other. Thus this distance seems very close to astronomers, much closer, for example, than our closest neighbor star Proxima Centauri at 4.2 light years. And most stars are vastly farther than Proxima Centauri.

Enjoying EarthSky so far? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

The astronomers say they are 98% certain that Scholz’s star swept through the outer Oort Cloud – a region at the edge of the solar system filled with trillions of comets a mile or more across. This, then, is an example of that passing star we’ve all heard about for decades, thought to give rise to long-period comets, those that take longer than about 200 years to orbit the sun, which we observe from time to time plummeting in toward the sun that binds them in orbit. The beautiful Comet Lovejoy seen and photographed by so many in January, 2015 was an example of a long-period comet.

But wait. Aren’t passing stars – and perturbations to the Oort Cloud – also supposed to cause comet showers, bursts of comets from the Oort Cloud heading inward toward the inner solar system, possibly to collide with the inner planets like Earth? The astronomers say that – in the case of Scholz’s star – the answer is no, and here’s why. According to a statement from University of Rochester:

Mamajek worked with former University of Rochester undergraduate Scott Barenfeld (now a graduate student at Caltech) to simulate 10,000 [possible] orbits for [Scholz’s] star, taking into account the star’s position, distance, and velocity, the Milky Way galaxy’s gravitational field, and the statistical uncertainties in all of these measurements. Of those 10,000 simulations, 98% of the simulations showed the star passing through the outer Oort cloud, but fortunately only one of the simulations brought the star within the inner Oort cloud, which could trigger so-called ‘comet showers.’

In other words, there’s a one in 10,000 chance that Scholz’s star triggered comet showers. But (good news, doomsday-ers!) that doesn’t let us off the hook for comet showers yet. Mamajek points out that:

… other dynamically important Oort Cloud perturbers may be lurking among nearby stars.

Currently, says Mamajet’s team, Scholz’s star is a small, dim red dwarf in the constellation of Monoceros, about 20 light-years away. However:

… at the closest point in its flyby of the solar system, Scholz’s star would have been a 10th magnitude star – about 50 times fainter than can normally be seen with the naked eye at night. It is magnetically active, however, which can cause stars to flare and briefly become thousands of times brighter. So it is possible that Scholz’s star may have been visible to the naked eye by our ancestors 70,000 years ago for minutes or hours at a time during rare flaring events.

Read more about Scholz’s star via University of Rochester

Bottom line: An international team of astronomers has concluded a study of Scholz’s star, saying that it passed close to our solar system in astronomical terms, only 0.8 light-years from our sun. The star system swept through our sun’s outer Oort comet cloud only 70,000 years ago. Scholz’s star has now passed closer to our solar system than any other known star – five times closer than the current closest star, Proxima Centauri.