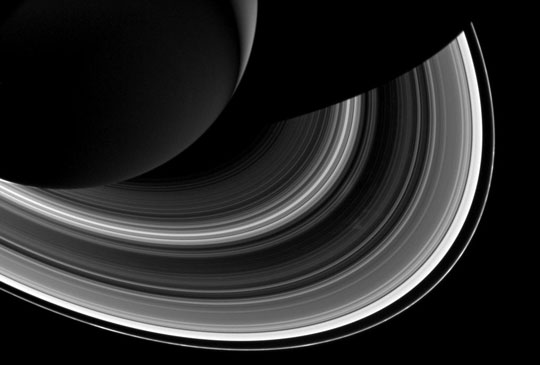

A single image like that above – of Saturn and its glorious rings – doesn’t really convey the reality of worlds in our solar system: that is, they are dynamic places, where things are happening! Turns out small moons are being born and then are destroyed on a very fast timescale, relative to solar system history, within Saturn’s F ring. Scientists Robert French and Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute carefully examined photos made by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, in contrast to 30-year-old images from the Voyager spacecraft. There were differences, they say, that can be explained by the birth and death of moonlets.

Voyager saw many bright spots coming and going in Saturn’s F ring, over the course of hours or days. Cassini has seen few of these bright areas. Robert French said:

The F ring is a narrow, lumpy feature made entirely of water ice that lies just outside the broad, luminous rings A, B, and C.

It has bright spots. But it has fundamentally changed its appearance since the time of Voyager. Today, there are fewer of the very bright lumps.

We believe the most luminous knots occur when tiny moons, no bigger than a large mountain, collide with the densest part of the ring. These moons are small enough to coalesce and then break apart in short order.

The F ring is located at a special distance from Saturn known as the Roche limit. Outside the Roche limit, moons can more easily form and stay whole. Inside it, the difference in the gravitational tug on moon’s near and far side might tear the moons apart, unless their internal strength and friction of their materials prevents this from happening.

So scientists are not surprised to see this evidence of moonlets forming and being destroyed in Saturn’s F ring. They say the moons in question are typically no more than 3 miles (5 km) in size. They come together quickly and quickly are destroyed.

Saturn’s F ring is very thin, just a few hundred kilometers in radial extent. It’s held together by two shepherd moons, Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit inside and outside it. These scientists say the inner moon Prometheus – a moon roughly 60 miles (100 km) in size – aligns with the F ring every 17 years in a way that emphasizes its gravitational influence on the ring’s particles. They believe this extra pull by Prometheus precipitates the formation of the moonlets. Showalter said:

These newborn moonlets will repeatedly crash through the F ring, like bumper cars, producing bright clumps as they careen through lanes of material. But this is self-destructive behavior, and the moons – being just at the Roche limit – are barely stable and quickly fragment.

Read more about the birth and death of moonlets in Saturn’s F ring, from SETI Institute

Bottom line: Scientists at the SETI Institute compared old Voyager spacecraft images to new images from the Cassini spacecraft. They found far fewer luminous knots in the F ring in the more recent images. They believe tiny moons, no bigger than large mountains, may coalesce and collide with the densest part of the ring, creating luminous knots. The moons come and go in a 17-year cycle, initiated by Saturn’s moon Prometheus.