New observations by large radio telescopes reveal that within a well-defined boundary around our galaxy, dwarf galaxies are completely devoid of hydrogen gas. Beyond this point, dwarf galaxies are teeming with star-forming material.

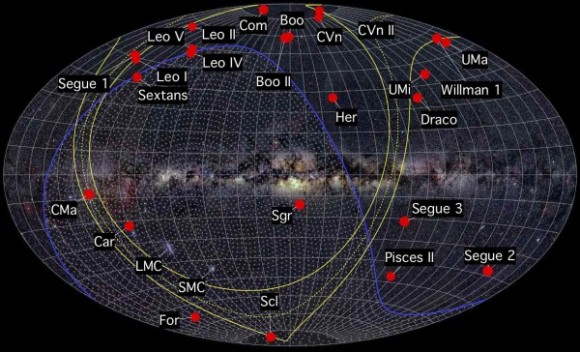

The Milky Way galaxy is actually the largest member of a compact clutch of galaxies that are bound together by gravity. Swarming around our home galaxy is a menagerie of smaller dwarf galaxies, the smallest of which are the relatively nearby dwarf spheroidals, which may be the leftover building blocks of galaxy formation. Further out are a number of similarly sized and slightly misshaped dwarf irregular galaxies, which are not gravitationally bound to the Milky Way and may be relative newcomers to our galactic neighborhood.

Kristine Spekkens is an assistant professor at the Royal Military College of Canada and lead author on a paper published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. She said:

Astronomers wondered if, after billions of years of interaction, the nearby dwarf spheroidal galaxies have all the same star-forming ‘stuff’ that we find in more distant dwarf galaxies.

Artist’s impression of the Milky Way. Its hot halo appears to be stripping away the star-forming atomic hydrogen from its companion dwarf spheroidal galaxies. Image credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

Previous studies have shown that the more distant dwarf irregular galaxies have large reservoirs of neutral hydrogen gas, the fuel for star formation. These past observations, however, were not sensitive enough to rule out the presence of this gas in the smallest dwarf spheroidal galaxies.

By bringing to bear the combined power of the National Science Foundation’s Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia (the world’s largest fully steerable radio telescope) and other giant telescopes from around the world, Spekkens and her team were able to probe the dwarf galaxies that have been swarming around the Milky Way for billions of years for tiny amounts of atomic hydrogen. Spekkens said:

What we found is that there is a clear break, a point near our home galaxy where dwarf galaxies are completely devoid of any traces of neutral atomic hydrogen.

Beyond this point, which extends approximately 1,000 light-years from the edge of the Milky Way’s star-filled disk to a point that is thought to coincide with the edge of its dark matter distribution, dwarf spheroidals become vanishingly rare while their gas-rich, dwarf irregular counterparts flourish.

There are many ways that larger, mature galaxies can lose their star-forming material, but this is mostly tied to furious star formation or powerful jets of material driven by supermassive black holes. The dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way contain neither of these energetic processes. They are, however, susceptible to the broader influences of the Milky Way, which itself resides within an extended, diffuse halo of hot hydrogen plasma.

The researchers believe that, up to a certain distance from the galactic disk, this halo is dense enough to affect the composition of dwarf galaxies. Within this “danger zone,” the pressure created by the million-mile-per-hour orbital velocities of the dwarf spheroidals can actually strip away any detectable traces of neutral hydrogen. The Milky Way thus shuts down star formation in its smallest neighbors.

Bottom lineL New observations by large radio telescopes reveal that within a well-defined boundary around our galaxy, dwarf galaxies are completely devoid of star-making hydrogen gas. Astronomers say our Milky Way is to blame.