It’s been part of the conventional wisdom of modern astronomy that mergers between galaxies – which are common throughout the history of the universe – lead to the formation of massive elliptical galaxies. That idea is based on computer simulations performed in the 1970s, which have held sway ever since. Now, however, astronomers have the first evidence that merging galaxies can create disk galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement published their result in August 2014.

Our own Milky Way is considered a disk galaxy. Disk galaxies include galaxies with prominent spiral arms like our own Milky Way and those with less-defined features known as lenticular galaxies. They’re characterized by a flattened, circular region of dust and gas. On the other hand, elliptical galaxies have an ellipsoidal shape, somewhat like American-style footballs.

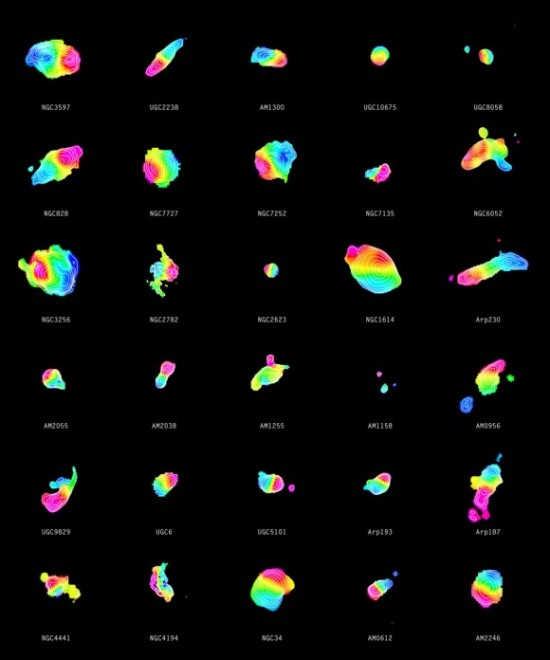

An international research group led by Junko Ueda of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and other radio telescopes to survey a collection of 37 galaxies. The galaxies studied ranged between 40 million to 600 million light-years from Earth.

The observed galaxies are thought to be the products of earlier mergers, and yet, the team discovered, 24 of the 37 galaxies appear to have gas disks.

That discovery is contrary to conventional wisdom. Mergers between galaxies do not involve collisions of stars or solar systems; the stars in galaxies are so far apart that, when galaxies merge, they pass through one another without their stars touching, like two ghosts. Galaxy mergers do spark furious star formation, though, and they produce a kind of gravitational chaos which, for decades, was thought to shred the original structures of the merging galaxies, resulting in elliptically shaped galaxies with no clearly defined disk.

More current models suggest that galaxy mergers can also produce disk galaxies, though astronomers had not yet found the smoking gun evidence in merger remnants.

Now, apparently, they have that smoking gun in the form of the 24 observed galaxies, observed to have the beginnings of gas disks, while showing other signs of having undergone earlier mergers.

To study merging galaxies, the researchers used the ALMA telescope in Chile and other radio telescopes. They looked specifically at the emission from carbon monoxide (CO) gas, which serves as a tracer for molecular gas in galaxies. The observations revealed signs of rotation and a flattened disk-like structure for the 24 galaxies. The astronomers said in a press release:

The group detected this rotation by studying how the wavelengths of radio emission shifted to higher and lower frequencies due to the motion of the gas. The researchers observed that the radio emission shifted toward the higher blue end of the spectrum in one portion of the disk – meaning it is moving toward us — and toward the lower red end of the spectrum in the other – meaning it is moving away. This telltale Doppler signature is indicative of rotation in a disk.

Lead astronomer Junko Ueda said:

For the first time, there is observational evidence for merging galaxies resulting in disk galaxies, not elliptical galaxies. This is a large and unexpected step towards understanding the mystery of the birth of disk galaxies.

We have to start focusing on the formation of stars in these gas disks. Furthermore, we need to look farther out in the more distant Universe. We know that the majority of galaxies in the more distant universe also have disks. We however do not yet know whether galaxy mergers are also responsible for these, or whether they are formed by cold gas gradually falling into the galaxy.

Maybe we have found a general mechanism that applies throughout the history of the universe.

Bottom line: Astronomers thought mergers formed giant elliptical galaxies. Now, for at least 24 galaxies, observed by the ALMA telescope and other radio telescopes, galaxy mergers appear to have formed flattened, circular disks of dust and gas.