The last woolly mammoths on Earth lived out their lives in isolation on Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia. They’re thought to have survived until about 1650 B.C. (over a thousand years after the building of the Pyramids at Giza). Scientists long believed these creatures perished due to inbreeding. But a group of researchers at Stockholm University said on June 27, 2024, that a new analysis of DNA recovered from woolly mammoth remains calls that assumption into question. The research shows that even though the island’s woolly mammoth population had low levels of genetic diversity, that fact alone wasn’t enough to cause their demise. The new findings have deepened the mystery of what caused these iconic ice age creatures to go extinct.

The scientists published their peer-reviewed study in the journal Cell on June 27, 2024.

Woolly mammoths’ last stand on Wrangel Island

Woolly mammoths are an extinct species of elephant. They were enormous, about the size of modern African elephants, with large, long tusks. These creatures also had a thick coat of fur that allowed them to thrive during the ice ages. Woolly mammoths once roamed tundra habitats of Asia, North America and Europe. But by the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago, they were mostly gone. Their declining numbers were due to the warming climate reducing their habitat. Plus, they began to be hunted by humans.

Even so, several isolated populations persisted for a few more thousand years. The last woolly mammoths are thought to have been those on Wrangel Island, located in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of northern Russia.

Wrangel Island is thought to have started with a small herd of woolly mammoths, when the island was cut off from the mainland by melting ice across Earth’s globe, and rising sea levels. around 10,000 years ago. According to the scientists, that original population on Wrangel Island may have numbered just eight individuals, at most. But the animals survived on the island for another 6,000 years, for more than 200 generations. During that time, they grew in numbers to some 200 to 300 individuals.

Genetic diversity needed to thrive

Robust genetic diversity is necessary for a species to thrive, remain fit and adapt to changes in the environment, new diseases and habitat loss. For a long time, conventional wisdom held that the Wrangel Island woolly mammoths died out because of a low level of genetic diversity. However, even though DNA analysis of their remains showed signs of inbreeding, the researchers concluded that was not the reason these creatures perished. Something else must have happened.

Love Dalén, a co-author from Stockholm University, said:

We can now confidently reject the idea that the population was simply too small and that they were doomed to go extinct for genetic reasons. This means it was probably just some random event that killed them off, and if that random event hadn’t happened, then we would still have mammoths today.

Answers and more questions from woolly mammoth DNA

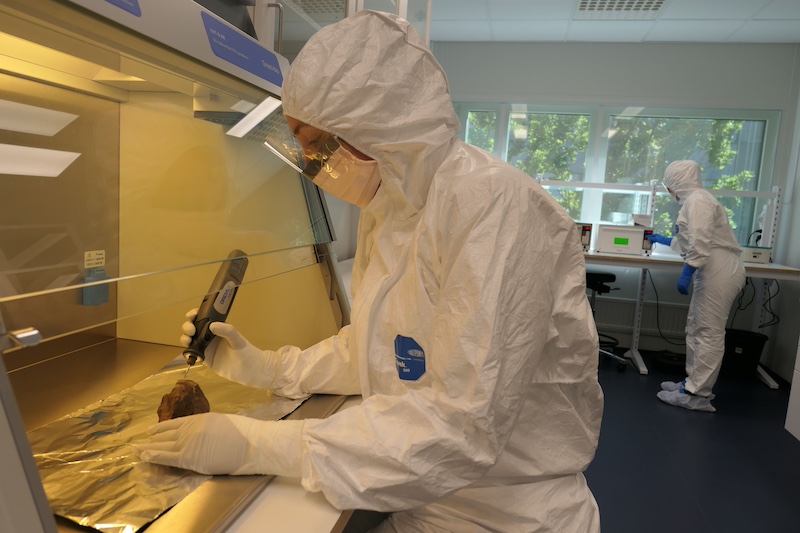

The researchers used DNA samples from the remains of 21 woolly mammoths. Of those, 14 samples came from Wrangel Island. The other seven samples came from woolly mammoths that once lived in Siberia, before Wrangel Island was cut off from the mainland. In all, they analyzed genetic material from individuals that lived during the last 50,000 years of the species’ existence. That provided researchers with data to study how woolly mammoth genetic diversity varied during that time.

Inbreeding, but not the end

The scientists confirmed the isolated Wrangel Island woolly mammoths, when compared to the Siberian mainland animals, were inbred and had low levels of genetic diversity. However, despite the genetic bottleneck – descending from just a few individuals – the Wrangel Island population recovered. They survived on the island for another 6,000 years.

During that period, the researchers found the population’s genetic diversity was in slow decline but remained stable. The woolly mammoths had accumulated moderately harmful genetic mutations, but the animals did not pass down highly harmful mutations to subsequent generations.

Scientists are continuing to investigate what happened to the woolly mammoths on Wrangel Island. The genetic material they analyzed did not include the final 300 years before the species went extinct. But they have since found woolly mammoth remains from that timeframe and plan more genetic studies.

Dalén remarked:

What happened at the end is a bit of a mystery still. We don’t know why they went extinct after having been more or less fine for 6,000 years, but we think it was something sudden. I would say there is still hope to figure out why they went extinct, but no promises.

Research from woolly mammoths could help endangered species today

Marianne Dehasque of Stockholm University, the paper’s lead author, said that this research has implications for understanding how to manage populations of endangered animals today:

Mammoths are an excellent system for understanding the ongoing biodiversity crisis and what happens from a genetic point of view when a species goes through a population bottleneck because they mirror the fate of a lot of present-day populations.

If an individual has an extremely harmful mutation, it’s basically not viable. So those mutations gradually disappeared from the population over time. But on the other hand, we see that the mammoths were accumulating mildly harmful mutations almost up until they went extinct. It’s important for present day conservation programs to keep in mind that it’s not enough to get the population up to a decent size again; you also have to actively and genetically monitor it because these genomic effects can last for over 6,000 years.

Bottom line: Scientists have long thought the last woolly mammoths of Wrangel Island, in Russia, died out 4,000 years ago due to inbreeding. New DNA analysis of their remains now questions that assumption.

Source: Temporal dynamics of woolly mammoth genome erosion prior to extinction