By Francesco Fiondella

The Elqui River basin in Chile’s Coquimbo region is one of the driest places on Earth. It receives only about 100 millimeters (4 inches) of rain each year, and most of it during one short rainy season. The rainfall is also highly variable. In some years, the region will get close to zero rainfall, while in others it will get five times the normal amount. All of this presents quite a challenge to those managing the Elqui basin’s water resources, which provides drinking water for two cities and irrigation for large vineyards, small farmers and goat herders.

The Elqui River is fed by snowmelt from the Andes and that collects in two large reservoirs, one of which is the Puclaro Reservoir. A widespread, multiyear drought that started in 2009 has depleted the Puclaro to only 10 percent of its capacity as of May 2013. Old villages that were abandoned and inundated after the Puclaro dam was built are now completely exposed and bone dry.

Since 2010, the Earth Institute’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society along with UNESCO and their colleagues in Chile have been working with Elqui’s water authority to help them use seasonal forecasts as way to better allocate water and prepare for droughts.

The water authority used these forecasts to generate water availability estimates for the first time in 2012. Now the goal is to better-integrate the climate information into policies that impact water management across the region.

The photos below will introduce you to the Elqui basin and some of the scientific work currently underway which is intended to help the region cope with persistent drought.

The Elqui River Valley is in Coquimbo, Chile’s most mountainous region.

It is also the most narrow part of the country, where the mountains are an everpresent backdrop, even at the Pacific’s shore.

Coquimbo is a typical semi-arid or dryland area. Less then 100 millimeters of rain falls here, almost all of it during the short winter rainy season. It is one of the driest places on Earth.

On top of this, rain and snowfall are highly variable year-to-year. In the past, people have had to cope with drought conditions in one year and rainfall five times above average in the next. Cacti, shrubs and herbs dominate the natural landscape.

Scientists from Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society, UNESCO, the Water Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Zones in Latin America and the Caribbean and the Center for Advanced Research in Arid Zones are working with local authorities to help them better manage and allocate Coquimbo’s most precious resource: water.

This work has taken on new urgency and importance because of a persistent multi-year drought that began in 2009 and that has diminished water levels in the Puclaro Reservoir.

The reservoir, fed by the Elqui, irrigates thousands of hectares of farmland and supports drinking water for the cities of La Serena and Vicuña.

The Puclaro Reservoir is now almost completely dry, currently at 10% of its capacity as of May 2013. The below picture shows how low the water level has changed from its 2009 peak, indicated by the lighter coloring on the mountainside.

Water levels are so low, that we can walk through the streets of the original village of Gualliguaica, which was flooded when the Puclaro Dam was built in 1997. The ruins were once under 60 feet of water.

The long drought has made earning a living in the Elqui Valley very challenging for traditional rainfed farmers and goat herders.

Grape growers and other large operations with much more sophisticated water management strategies are also not immune to the drought’s effects.

Fundo El Algarrobal vineyard has been constructing its own, smaller reservoirs to store water in case the Elqui dries up completely.

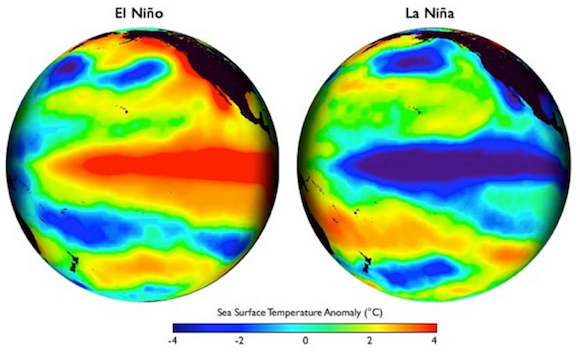

Rain and snowfall in Coquimbo can vary significantly from one year to the next. El Niño and La Niña in the tropical Pacific drive a significant part of this variability. Scientists routinely monitor these climate events as they unfold, and so are able to predict with fairly high confidence the impacts they’re going to have on Coquimbo’s precipitation months ahead of time.

The water authority that manages the Puclaro dam and the rest of the Elqui River is known as the Junta de La Vigilancia. José Izquierdo Zomosa is the Junta’s president.

Every year, the Junta issues estimates of water availability for the forthcoming growing season so that farmers like Dina Cifuentes and Bruno Espinoza Moran as well as other users can plan accordingly.

Scientists are working to better understand climate in the Coquimbo region of Northern Chile. The goal is to gather information for improved decision-making, both in short-term and decadal timescales. Andrew Robertson is a climate scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society.

Koen Verbist is a scientist who currently works at UNESCO Santiago. In 2010, Andrew Robertson and Verbist developed a seasonal forecast model to predict precipitation for the Coquimbo region using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and IRI’s powerful Climate Predictability Tool.

Their colleagues, Paul Block and Edmundo Gonzales, from Drexel University and the University of La Serena, respectively, developed an accurate model for the Elqui River that predicts the river’s streamflow for the upcoming season based on data from weather stations around Coquimbo.

IRI, UNESCO and the Water Centre for Arid Zones worked closely with the Junta to incorporate this scientific knowledge into its operations. In 2012, the water authority used seasonal forecasts for the first time to generate water estimates for the upcoming summer, and presented these scenarios at its annual meeting in September.

The success of this early work resulted from the strong collaboration among scientists, engineers and policy makers who used science in order to address a real and expressed societal need. The challenge now is to integrate climate forecasts and other information into policies that impact water management across the region.

All photos thanks to Francesco Fiondella

Bottom line: Scientists are working together with local authorities to learn more about the Elqui River Valley’s multi-year drought and what steps can be taken to mitigate its effects.