Best New Year’s gift ever! EarthSky moon calendar for 2019

Most hummingbirds have bills and tongues exquisitely designed to slip inside a flower, lap up nectar and squeeze every last drop of precious sugar water from their tongue to fuel their frenetic lifestyle.

But in the tropics of South America, scientists have found that some male hummers have traded efficient feeding for bills that are better at stabbing and plucking other hummingbirds as they fend off rivals for food and mates. The males’ weaponized bills are good not only for pulling feathers and pinching skin, but also wrestling their rivals away from prime feeding spots.

Using high-speed video cameras, the researchers captured hummingbird fencing and feeding strategies in slow motion to document the various ways the birds use their bills to fight and the trade-offs they accept when choosing fighting over feeding prowess.

University of California-Berkeley biologist Alejandro Rico-Guevara is lead author of a study, published January 2, 2019, in the journal Integrative Organismal Biology, describing how bill shape affects hummingbird feeding and fighting strategies. Rico-Guevara said in a statement:

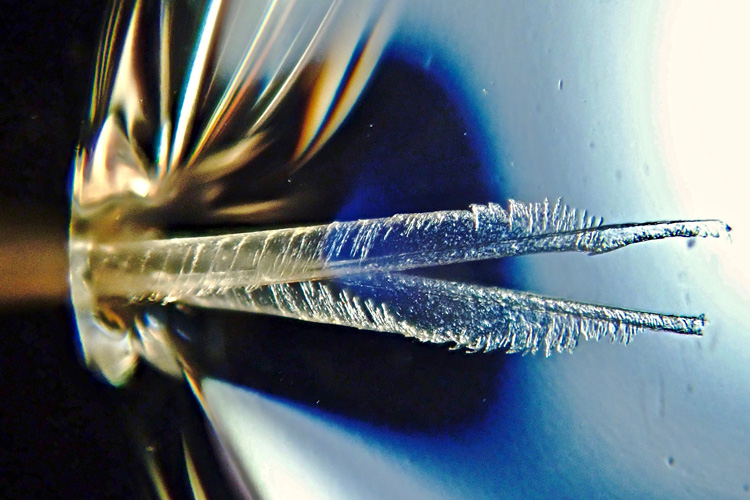

We understand hummingbirds’ lives as being all about drinking efficiently from flowers, but then suddenly we see these weird morphologies – stiff bills, hooks and serrations like teeth – that don’t make any sense in terms of nectar collection efficiency.

Rico-Guevara said that hummingbirds have long been known as fierce fighters – they even attack hawks, owls and other birds if they perceive a threat – but the fights happen so fast that scientists haven’t been able to see the actual outcome. He said:

Because it happens so fast and they fly away, you can’t track them. But also, people haven’t actually looked at the details of the beaks. We are making connections between how feisty they are, the beak morphology behind that and what that implies for their competitiveness.

In the new paper, Rico-Guevara describes what he has discovered to date about the exquisite beak design that most hummingbirds, including North American hummers, have evolved for feeding, and the unique features of hummingbirds’ forked tongues. He said.

Extracting nectar is what fuels their lives. As a result, they have developed very flexible bills with very soft edges, soft, blunt bill tips that are concave, like a couple of spoons, that perfectly match the tongue to squeeze out the last drop of nectar. All of these traits make a good seal between the tongue tips that actually enhances the efficiency of nectar extraction.

Yet in the tropics, including Colombia, Brazil, Peru and Costa Rica, males of many species don’t fit this picture. Instead, they have stiff bills with a hard, conical, dagger-like tip, often hooked, plus rear-facing serrations like the teeth of a comb. High-speed video shows that the stiff, hard-tipped bill is ideal for poking other birds, while the hooked tip and serrations are a perfect way to snatch a feather or two. The males’ wings are also adapted to be more aerodynamic – for in-flight fights – than are female wings.

Not all fighters use their bills to protect their food. Others use their bills primarily to out-fence males competing for females at gathering places called leks. Rico-Guevara said:

A lek is like a singles bar, a place where many males get together and sing, sing, sing all the time. The females go to these small spaces in the forest and pick a male to mate with. If you can get a seat at that bar, it is going to give you the opportunity to reproduce. So they don’t fight for access to resources, like in the territorial species, but they actually fight for an opportunity to reproduce. And in the brief moments when there is no fighting, they go to feed on different flowers.

Bottom line: New research shows that some hummingbirds have evolved specialized bills for fighting.

Source: Shifting Paradigms in the Mechanics of Nectar Extraction and Hummingbird Bill Morphology