By Catesby Holmes, The Conversation

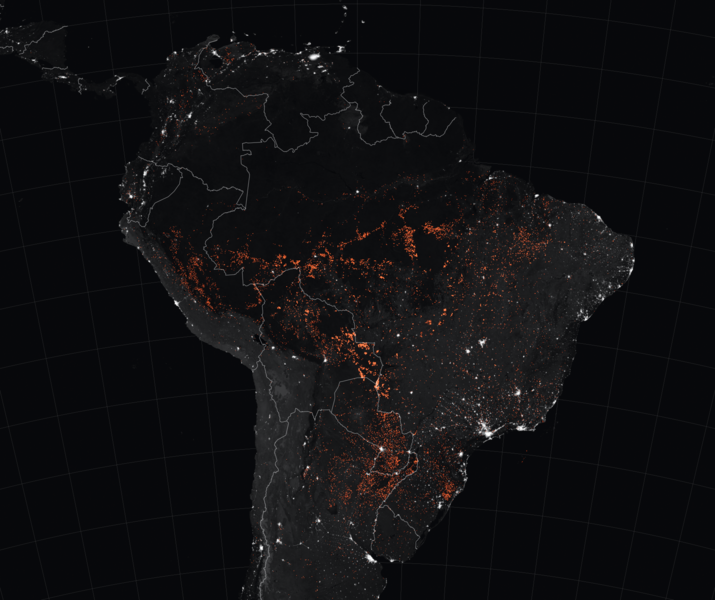

Nearly 40,000 fires are incinerating Brazil’s Amazon rainforest, the latest outbreak in an overactive fire season that has charred 1,330 square miles (2,927 square km) of the rainforest this year.

Don’t blame dry weather for the swift destruction of the world’s largest tropical forest, say environmentalists. These Amazonian wildfires are a human-made disaster, set by loggers and cattle ranchers who use a “slash and burn” method to clear land. Feeding off very dry conditions, some of those fires have spread out of control.

Brazil has long struggled to preserve the Amazon, sometimes called the “lungs of the world” because it produces 20% of the world’s oxygen. Despite the increasingly strict environmental protections of recent decades, about a quarter of this massive rainforest is already gone – an area the size of Texas.

While climate change endangers the Amazon, bringing hotter weather and longer droughts, development may be the greatest threat facing the rainforest.

Here, environmental researchers explain how farming, big infrastructure projects and roads drive the deforestation that’s slowly killing the Amazon.

1. Farming in the jungle

Rachel Garrett is a professor at Boston University who studies land use in Brazil. She said:

Deforestation is largely due to land clearing for agricultural purposes, particularly cattle ranching but also soybean production.

Since farmers need a massive amount of land for grazing, Garrett says, they are driven to

… continuously clear forest – illegally – to expand pastureland.

Twelve percent of what was once Amazonian forest – about 93 million acres – is now farmland.

Deforestation in the Amazon has spiked since the election last year of the far-right President Jair Bolsonaro. Arguing that federal conservation zones and hefty fines for cutting down trees hinder economic growth, Bolsonaro has slashed Brazil’s strict environmental regulations.

There’s no evidence to support Bolsonaro’s view, Garrett says. She said:

Food production in the Amazon has substantially increased since 2004.

The increased production has been pushed by federal policies meant to discourage land clearing, such as hefty fines for deforestation and low-interest loans for investing in sustainable agricultural practices. Farmers are now planting and harvesting two crops – mostly soybeans and corn – each year, rather than just one.

Brazilian environmental regulations helped Amazonian ranchers, too.

Garrett’s research found that improved pasture management in line with stricter federal land use policies led the number of cattle slaughtered annually per acre to double. She wrote:

Farmers are producing more meat – and therefore earning more money – with their land.

2. Infrastructure development and deforestation

President Bolsonaro is also pushing forward an ambitious infrastructure development plan that would turn the Amazon’s many waterways into electricity generators.

The Brazilian government has long wanted to build a series of big new hydroelectric dams, including on the Tapajós River, the Amazon’s only remaining undammed river. But the indigenous Munduruku people, who live near the Tapajós River, have stridently opposed this idea.

According to Robert T. Walker, a University of Florida professor who has conducted environmental research in the Amazon for 25 years:

The Munduruku have until now successfully slowed down and seemingly halted many efforts to profit off the Tapajós.

But Bolsonaro’s government is less likely than his predecessors to respect indigenous rights. One of his first moves in office was to transfer responsibilities for demarcating indigenous lands from the Brazilian Ministry of Justice to the decidedly pro-development Ministry of Agriculture.

And, Walker notes, Bolsonaro’s Amazon development plans are part of a broader South American project, conceived in 2000, to build continental infrastructure that provides electricity for industrialization and facilitates trade across the region.

For the Brazilian Amazon, that means not just new dams but also “webs of waterways, rail lines, ports and roads” that will get products like soybeans, corn and beef to market, according to Walker. He said:

This plan is far more ambitious than earlier infrastructure projects that damaged the Amazon.

If Bolsonaro’s plan moves forward, he estimates that fully 40 percent of the Amazon could be deforested.

3. Road-choked streams

Roads, most of them dirt, already criss-cross the Amazon.

That came as a surprise to Cecilia Gontijo Leal, a Brazilian researcher who studies tropical fish habitats. She wrote:

I imagined that my field work would be all boat rides on immense rivers and long jungle hikes. In fact, all my research team needed was a car.

Traveling on rutted mud roads to take water samples from streams across Brazil’s Pará state, Leal realized that the informal “bridges” of this locally built transportation network must be impacting Amazonian waterways. So she decided to study that, too. She said:

We found that makeshift road crossings cause both shore erosion and silt buildup in streams. This worsens water quality, hurting the fish that thrive in this delicately balanced habitat.

The ill-designed road crossings – which feature perched culverts that disrupt water flow – also act as barriers to movement, preventing fish from finding places to feed, breed and take shelter.

4. Rewilding tropical forests

The fires now consuming vast swaths of the Amazon are the latest repercussion of development in the Amazon.

Set by farmers likely emboldened by their president’s anti-conservation stance, the blazes emit so much smoke that on August 20 it blotted out the midday sun in the city of São Paulo, 1,700 miles (2,736 km) away. The fires are still multiplying, and peak dry season is still a month away.

Apocalyptic as this sounds, science suggests it’s not too late to save the Amazon.

Tropical forests destroyed by fire, logging, land-clearing and roads can be replanted, say ecologists Robin Chazdon and Pedro Brancalion.

Using satellite imagery and the latest peer-reviewed research on biodiversity, climate change and water security, Chazdon and Brancalion identified 385,000 square miles (997,145 square km) of “restoration hotspots” – areas where restoring tropical forests would be most beneficial, least costly and lowest risk. Chazon wrote:

Although these second-growth forests will never perfectly replace the older forests that have been lost, planting carefully selected trees and assisting natural recovery processes can restore many of their former properties and functions.

The five countries with the most tropical restoration potential are Brazil, Indonesia, India, Madagascar and Colombia.

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

Catesby Holmes, Global Affairs Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Causes of wildfires burning Brazil’s Amazon rainforest in August 2019.

![]()