The Royal Astronomical Society in the U.K. originally published this post in July 2021.

Caroline Herschel Medal to honor women

A new prize to celebrate outstanding research by women astrophysicists was made public earlier this month (July 2021) by Britain’s prime minister, Boris Johnson. It is the latest initiative to recognize the game-changing contribution of women in a field that is hugely dominated by men.

The £10,000 [about $14,000 USD] prize – to be given in alternate years to researchers based in the U.K. and Germany – was announced by Johnson to mark the final U.K. visit by Angela Merkel (a scientist by training) as German chancellor. The award is named for Caroline Herschel (1750–1848) who was a pioneer in astronomy at a time when women were rarely recognized for their contributions to the field.

In times past, a female astronomer was traditionally paired with a male astronomer: she carried out the deep-space observations and data analysis while her research partner wrote the academic papers and received the accolades. Thankfully, female astronomers are now in a position to stand alone in receiving the recognition they rightly deserve. However, there is much work to be done before they achieve parity with their male colleagues.

Today in the U.K., 12% of professors, 18% of senior lecturers/readers, and 29% of lecturers in astronomy are women. In solar system science, women make up 21% of professors, 22% of senior lecturers/readers, and 27% of lecturers (see the 2016 Survey of Demographics and Research Interests of the U.K. Astronomy and Geophysics Communities for details). Girls comprise just one in five A-level physics entrants, a proportion largely unchanged for many years, and women make up around 3/10 of undergraduate students in astronomy courses.

Yet despite the clear odds against women space scientists rising to the top, an impressive number of remarkable female astronomers are now recognized for the mark they have left – or are still leaving – on the world.

Influential women in astronomy, now and in years past

Here is a collection of the female superstars who are rightly recognized today for their extraordinary work in astronomy (more can be found here):

Caroline Herschel (1750-1848): German astronomer, active in the U.K. Despite being struck with typhus aged 10 and suffering vision loss in one eye, Herschel went on to discover (among other things) several comets, including the periodic comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet, which is named after her. She was the first woman to receive a pension from the king. She was also awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) in 1828.

Williamina Fleming (1857–1911): Scottish astronomer, active in the US. She helped develop a common designation system for stars and cataloged thousands of stars and other astronomical phenomena. She discovered a total of 59 gaseous nebulae, over 310 variable stars, and 10 novae.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921): American astronomer whose discoveries gave astronomers their first ‘standard candle’ (an astronomical object with a known luminosity), allowing them to measure the distance to faraway galaxies. Using Leavitt’s work, astronomers were able to measure distances of up to about 20 million light-years.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900-1979): British-born American astronomer and astrophysicist who proposed in her 1925 doctoral thesis that stars were composed primarily of hydrogen and helium. Her conclusion was initially rejected because it contradicted the scientific wisdom of the time but independent observations eventually proved she was correct.

Vera Rubin (1928-2016): American astronomer whose observational work on the rotation of galaxies showed that, in nearly all spiral galaxies, stars far from the galactic center orbit much faster than expected, strongly supporting the contention that galaxies are surrounded by haloes of unseen ‘dark matter.’ In 1996 Rubin was awarded a RAS Gold Medal for her work, the first woman to receive this honor since Caroline Herschel 168 years earlier. Her observations also provided evidence of the existence of galactic superclusters. Rubin was a passionate advocate for women in science and was an active mentor of aspiring female astronomers. She was the first woman to have a large observatory named after her: the Rubin Observatory in Chile.

Beatrice Tinsley (1941-1981): British-born New Zealand astronomer and professor of astronomy at Yale University. Her research made key contributions to our understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow, and die.

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell: Astrophysicist from Northern Ireland who discovered the first radio pulsars (rapidly rotating, highly magnetized neutron stars) when she was still a student in 1967. The discovery was recognized in 1974 by the award of the Nobel Prize in Physics, though Dame Jocelyn was not a recipient of the prize, almost certainly because she was a woman. She is also a former president of a number of institutions: the RAS, the Institute of Physics, and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. She is widely recognized for her many science prizes and her advocacy work for women in STEM.

Sandra Faber: American astrophysicist known for her research on the evolution of galaxies. She is a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California and has made important discoveries linking the brightness of galaxies to the speed of stars within them.

Yvonne Elsworth: Irish physicist based at the School of Physics and Astronomy, the University of Birmingham (she is professor of helioseismology – the study of the structure and dynamics of the sun through its oscillations – and Poynting professor of physics). Until 2015, Professor Elsworth was also the head of the Birmingham Solar Oscillations Network (BiSON), the longest-running helioseismology network, with data covering well over three solar cycles (the cycles the sun’s magnetic field goes through approximately every 11 years).

Victoria Kaspi: Canadian astrophysicist and professor of physics at McGill University. She works on neutron stars, using X-ray telescopes to study pulsars. She was recognized by Nature as one of Nature’s 10 (ten people who helped shape science in 2019) for her work on discovering fast radio bursts with the CHIME telescope, and in 2021 was awarded the prestigious Shaw Prize, also referred to as the Nobel of the East.

Carole Mundell: British professor of extragalactic astronomy, and head of astrophysics, at the University of Bath. Professor Mundell is an observational astrophysicist who researches cosmic black holes and gamma-ray bursts. She is also the first woman to hold the role of chief scientific adviser at the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, and the first person to hold the role of chief international science envoy. In 2021, she was named the Hiroko Sherwin chair in Extragalactic Astronomy. Her career highlights include the Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award (2011 to 2016) for the study of black hole-driven explosions and the dynamic universe and the FDM Everywoman in Technology Woman of the Year award (2016). Professor Mundell is a passionate champion of diversity and women in STEM.

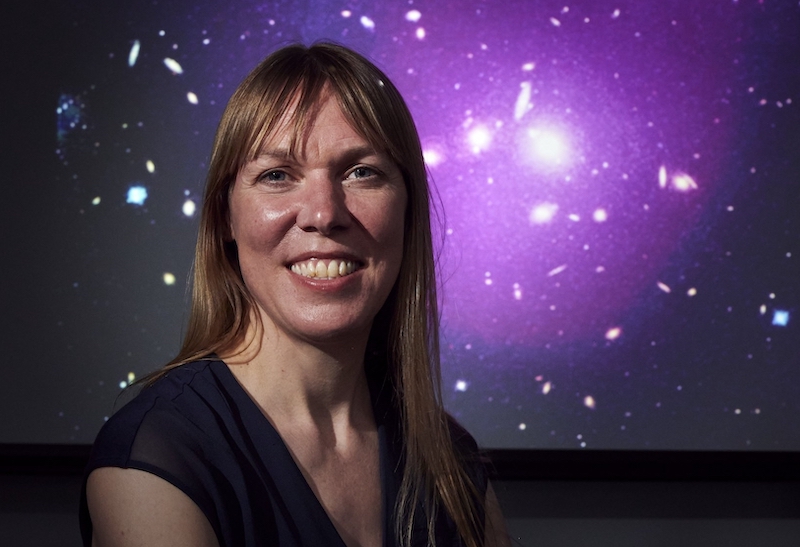

Catherine Heymans: Astronomer Royal for Scotland (the only woman to have held any of the astronomer royal positions in the U.K.); professor of astrophysics and European Research Council Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. Professor Heymans is also the Director of the German Centre for Cosmological Lensing at the Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany. Her main area of research is the dark universe using weak gravitational lensing.

Samaya Nissanke: British astrophysicist based in the Netherlands, associate professor in gravitational wave and multi-messenger astrophysics, and the spokesperson for the GRAPPA Centre for Excellence in Gravitation and Astroparticle Physics at the University of Amsterdam. She works on gravitational-wave astrophysics and has played a founding role in the emerging field of multi-messenger astronomy. She also played a leading role in the discovery paper of the first binary neutron star merger, GW170817. In 2020, she was jointly awarded the New Horizons in Physics Prize from the Breakthrough Prize Foundation. In 2021, she was awarded a Suffrage Award for Engineering and Physical Sciences.

Juna Kollmeier: U.S. astrophysicist at the Carnegie Institution of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Her primary focus is on the emergence of structure in the universe. She combines cosmological hydrodynamic simulations and analytic theory to figure out how the tiny fluctuations in density that were present when the universe was only 300 thousand years old, become the galaxies and black holes that we see now, after 14 billion years of cosmic evolution.

Emma Bunce: British astrophysicist and professor of Planetary Plasma Physics at the University of Leicester. Professor Bunce is also president of the Royal Astronomical Society and the holder of the Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award. Her research is on the magnetospheres of Saturn and Jupiter (the cavities created in the flow of the solar wind by the planets’ internally generated magnetic fields).

Bottom line: In the run-up to the Royal Astronomical Society’s annual meeting, the prime minister of the United Kingdom announced an important new prize, the Caroline Herschel Medal, for women astronomers. The award highlights the need for women to be recognized for their outstanding work in astronomy.