Emily Lakdawala at the Planetary Society posted an in-depth report today (August 19, 2014) about the ongoing wheel problems of NASA’s Mars Curiosity rover, which has been exploring the surface of the Red Planet since its dramatic touchdown just two years ago this month. Lakdawala writes of:

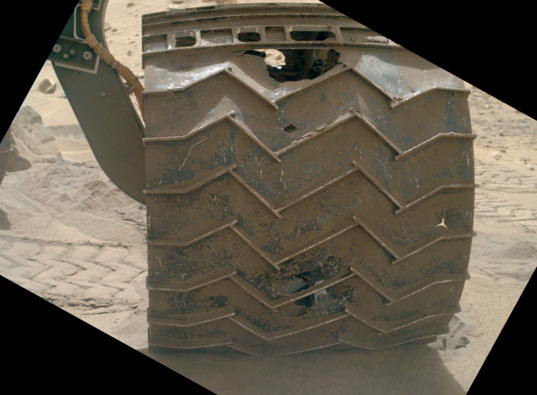

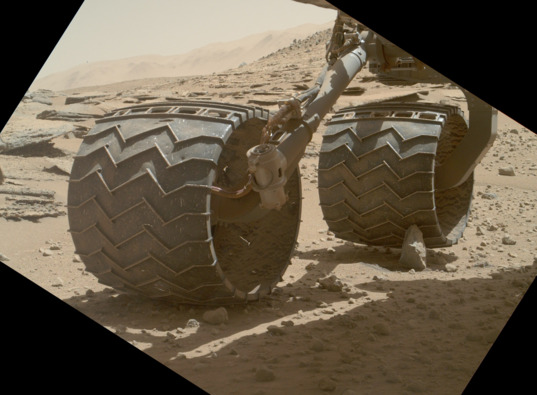

… punctures, fissures, and ghastly tears. The holes in Curiosity’s wheels have become a major concern to the mission, affecting every day of mission operations and the choice of path to Mount Sharp. Yet mission managers say that, so far, the condition of the wheels has no effect on the rover’s ability to traverse Martian terrain.

The mission did expect some damage to the wheels – some dings and scratches over time – but mission managers did not realize the extent of the damage being done until a large puncture appeared on sol 411 (or 411 Martian days after touchdown). By sol 463, a large rip had opened. Testing back on Earth has revealed the cause of the damage, which appears twofold.

First, the wheels (which are made of a very thin metal) are subject to fatigue, the same mechanism that will cause a paperclip to break in two if you bend it over and over. On Mars, as Curiosity’s wheels drive over a very hard rock surface – one with no sand – as the rover makes its way to Mount Sharp, the central peak of the Gale crater on Mars, the thin skin of the wheels repeatedly bends and ultimately tears.

Second, mission managers did not anticipate the exact nature of the rocks in and around Curiosity’s landing site and route to (the ironically named?) Mount Sharp. This area has many pyramid-shaped rock – pointy on top – that are firmly embedded in the ground. Lakawalla writes:

It turns out that there are mechanical aspects of the mobility system that actively shove the wheels into pointy rocks. A wheel can resist the force of one-sixth of the rover’s weight pressing down on a pointy rock, but it can’t resist the rover’s weight plus the force imparted by five other wheels shoving the sixth wheel into a pointy rock. The forces are worse for the middle and front wheels than they are for the rear wheels …

Again, though, these forces were understood before Curiosity launched to Mars, and are not, on their own, enough to cause the large punctures. If the pointy rock can move, all that pushing force behind it will just shift the pointy rock to one side or another, or it can roll beneath the wheel, and the wheel will get over it without damage. The key to wheel punctures is immobile pointy rocks. If the pointy rock is stuck in place, partially buried, or if it is a pointy bit of intact bedrock, then there’s nowhere for it to go. At the landing anniversary event, rover driver Matt Heverly showed a video of a test where they had a sharpened metal spike embedded in the ground, and drove a wheel over it. The spike pierced the wheel like a can opener slices into a can. The entire audience sucked in its teeth.

No place we’ve ever been on Mars before has these kinds of embedded, pointy rocks.

Lakdawala emphasizes that Curiosity’s wheel problems will not end the mission, but they will slow the mission down, as mission managers look for the smoothest terrain possible for the rover. She says:

The biggest effect of the wheel damage problem is to slow the mission down. And that’s what will limit how much Curiosity accomplishes. By not traveling as fast, and by having to limit their path choices, the amount of exploration that they can do is necessarily less than if they could go gallivanting across the bedrock outcrops at will.

Curiosity’s wheel problems are also being taken very seriously by planners for the next rover, on the Mars 2020 mission.

Read Emily Lakdawalla’s complete coverage of Curiosity’s wheel problems

Bottom line: Mission managers didn’t anticipate that Curiosity would be driving over an area on Mars that has pyramid-shaped rocks embedded into hard ground, as it traverses Mars.