Help EarthSky keep going! Please donate what you can to our annual crowd-funding campaign.

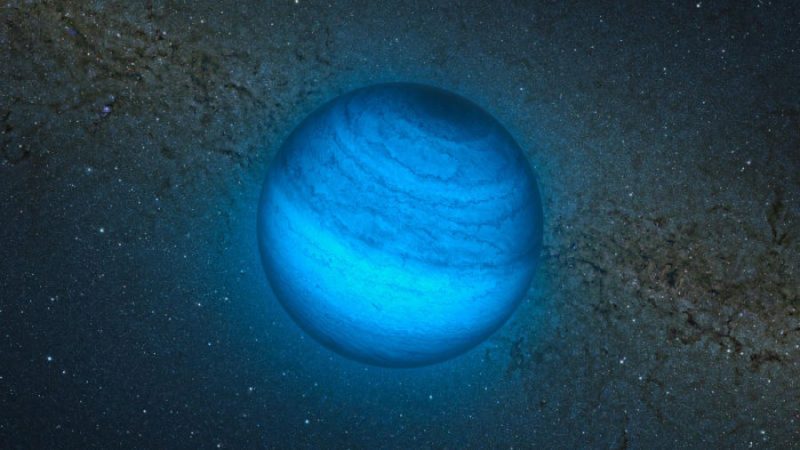

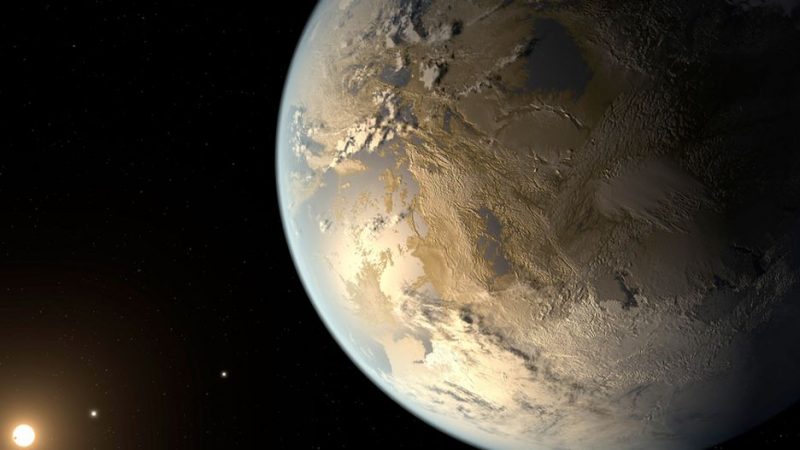

Based on findings from space- and ground-based telescopes in recent years, astronomers now estimate there are billions of exoplanets – planets orbiting distant stars – in our galaxy alone. But what about planets that don’t orbit stars? How many rogue, or free-floating planets wander the depths of space unbound? Some have already been found, and earlier this year astronomers at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands announced results of their new study, suggesting there are some 50 billion free-floating planets in our Milky Way galaxy.

These astronomers’ results were published on February 14, 2019, in the peer-reviewed journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Only a dozen or so rogue planets have been discovered. How did these astronomers’ research determine there might be 50 billion more?

They ran computer simulations of 1,500 stars in the Trapezium star cluster, a well-known region of star formation located some 1,300 light-years away in the Orion Nebula, in the direction of our constellation Orion.

The simulation included 2,522 planets orbiting 500 stars within the Trapezium cluster and showed that 357 of them would become free-floating planets within the first 11 million years of their evolution. Simon Portegies Zwart, an astronomer at the University of Leiden, recently told Bruce Dorminey of Forbes:

Of these, 281 leave the cluster, others remain bound to the cluster as free-floating intra-cluster planets.

So 281 of 2,522 newly born planets would leave their original star-forming cluster altogether, to roam the space between stars and star clusters, according to this computer simulation. The researchers then extrapolated those numbers to the rest of the galaxy, based on estimates of 200 billion stars in our galaxy. After all, the Trapezium star cluster is just one of thousands of known star clusters. All of the Milky Way’s stars are thought to have originated in vast star-forming clouds like those in the Orion Nebula, and to have started life in star clusters much like the Trapezium star cluster.

If, as calculated, about a quarter of the Milky Way’s stars have lost one or more planets, as many as 50 billion planets should be rogue or free-floating, in our galaxy alone!

Bound exoplanets likely outnumber stars in the galaxy; our single sun has eight major planets, and we’ve now seen thousands of planets orbiting single stars in multiple-planet systems. The estimates for the total numbers of planets in our Milky Way – both bound to stars, and rogue – is staggering.

Just a few decades ago, it wasn’t yet known if any exoplanets existed. Now, current observations suggest there are hundreds of billions. Combine that with the billions of galaxies, and the implications are mind-blowing.

Here is another question. Might any of those free-floating planets collide with other planets or with their stars? They can and do, according to these astronomers’ recent computer simulation. Zwart said in Forbes:

Collisions among planets and between planets and their host star are common. This happens in more than three percent of planetary systems.

Zwart also thinks that our own solar system might have lost one or two planets – probably less massive than Neptune – earlier in its youth. He said:

But who knows what happened very early on, when Jupiter and Saturn had just formed and the rocky planets just started to emerge.

The ejection of planets from their home planetary systems might be more common in denser star clusters (the Trapezium star cluster is considered a “looser” cluster), since more frequent encounters between stars in dense clusters will make the planetary systems unstable. But the study of the Trapezium cluster shows that planets leave their home systems in looser clusters as well.

Two of the dozen or so confirmed rogue planets so far were announced last year – OGLE-2012-BLG-1323 and OGLE-2017-BLG-0560. The first is estimated to have a mass between Earth and Neptune, while the other has a mass between Jupiter and a brown dwarf star.

Rogue planets are not easy to detect, but as astronomers learn more about them, they’ll be able to find more in the coming years. If this new study is any indication, there are many of them awaiting discovery.

Bottom line: The existence of 200 billion stars in our galaxy – and an even greater number of planets – is difficult enough to wrap our minds around. The idea of another 50 billion planets just floating around, not bound to any stars, is even more incredible. It might sound like science fiction, but, if astronomers at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands are right, these 50 billion rogue planets do exist.

Source: The survivability of planetary systems in young and dense star clusters