Using observations obtained with the Hubble Space Telescope and the large telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory, researchers found an excess of oxygen—a chemical signature that indicates that the debris had once been part of a bigger body originally composed of 26 percent water by mass.

Evidence for water outside our solar system has previously been found in the atmosphere of gas giants, but this is the first time it has been pinpointed in a rocky body, making it of significant interest in understanding of the formation and evolution of habitable planets and life.

The dwarf planet Ceres contains ice buried beneath an outer crust, and researchers have drawn a parallel between the two bodies. It’s believed that bodies like Ceres were the source of the bulk of our own water on Earth.

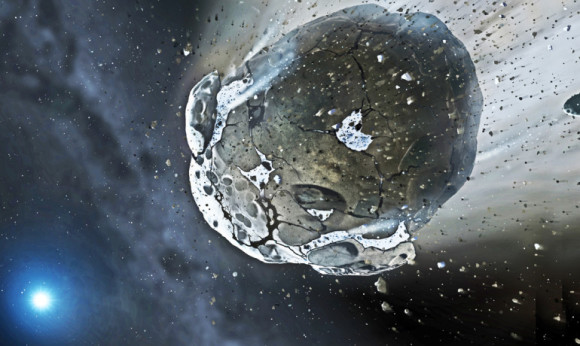

In the study published in Science, researchers suggest it is most likely that the water detected around the white dwarf GD 61 came from a minor planet at least 90 kilometers (56 miles) in diameter—but potentially much bigger—that once orbited the parent star before it became a white dwarf.

Bigger than the sun

Like Ceres, the water was most likely in the form of ice below the planet’s surface. From the amount of rocks and water detected in the outer envelope of the white dwarf, the researchers estimate that the disrupted planetary body had a diameter of at least 90 kilometers.

However, because their observations can only detect what is being accreted in recent history, the estimate of its mass is on the conservative side.

It is likely that the object was as large as Vesta, the largest minor planet in the solar system. In its former life, GD 61 was a star somewhat bigger than our Sun, and host to a planetary system.

About 200 million years ago, GD 61 entered its death throes and became a white dwarf, yet, parts of its planetary system survived. The water-rich minor planet was knocked out of its regular orbit and plunged into a very close orbit, where it was shredded by the star’s gravitational force.

Researchers believe that destabilizing the orbit of the minor planet requires a so far unseen, much larger planet going around the white dwarf.

Habitable planets?

“At this stage in its existence, all that remains of this rocky body is simply dust and debris that has been pulled into the orbit of its dying parent star,” says Boris Gänsicke, professor of physics at the University of Warwick.

“However this planetary graveyard swirling around the embers of its parent star is a rich source of information about its former life. In these remnants lie chemical clues which point towards a previous existence as a water-rich terrestrial body.

“Those two ingredients—a rocky surface and water—are key in the hunt for habitable planets outside our solar system so it’s very exciting to find them together for the first time outside our solar system.”

“The finding of water in a large asteroid means the building blocks of habitable planets existed—and maybe still exist—in the GD 61 system, and likely also around substantial number of similar parent stars,” says lead author Jay Farihi, from the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge.

“These water-rich building blocks, and the terrestrial planets they build, may in fact be common—a system cannot create things as big as asteroids and avoid building planets, and GD 61 had the ingredients to deliver lots of water to their surfaces.

“Our results demonstrate that there was definitely potential for habitable planets in this exoplanetary system.”

For their analysis, the researchers used ultraviolet spectroscopy data obtained with the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph on board the Hubble Space Telescope of the white dwarf GD 61.

As the atmosphere of the Earth blocks the ultraviolet light, such study can only be carried out from space. Additional observations were obtained with both of the 10m telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory on the summit of Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

The Hubble and Keck data allows the researchers to identify the different chemical elements that are polluting the outer layers white dwarf.

Using a sophisticated computer model of the white dwarf atmosphere, developed by Detlev Koester at the University of Kiel, they were able to infer the chemical composition of the shredded minor planet.

To date observations of 12 destroyed exoplanets orbiting white dwarves have been carried out, but this is the first time the signature of water has been found.