A pristinely-preserved fossil, 520 million years old, has revealed the earliest known central nervous system of an animal. This creature, the first of its kind ever discovered, belonged to a now-extinct group of animals that had a pair of long, forceps-like extensions from the head. They were known as megacheirans, which means large claws in Greek. The brain and nerve structures in the 3-centimeter-long fossil indicate it’s a distant relative of spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs. Scientists described the fossil, which was found at the Chengjiang formation near Kunming in southwest China, in the October 17, 2013 issue of Nature.

This discovery also casts new light on the early evolution of arthropods such as spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, insects, crustaceans, and milipedes. More than a half-billion years ago, the evolutionary course of arthropods split into two branches. One branch led to spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs, the other to insects, milipedes, and crustaceans.

University of Arizona Professor Nick Strausfeld , one of the paper’s authors, said in a press release:

We now know that the megacheirans had central nervous systems very similar to today’s horseshoe crabs and scorpions. This means the ancestors of spiders and their kin lived side by side with the ancestors of crustaceans in the Lower Cambrian.

The newly-discovered fossil belongs to a now-extinct group of marine animals known as Alalcomenaeus, a member of the megacheiran group. They had elongated segmented bodies with about a dozen pairs of limbs for crawling or swimming, as well as a distinctive pair of scissor-like protrusions from the head that was possibly used to sense and grasp prey.

Paleontologists have long thought that Alalcomenaeus were related to spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs because their fossils showed an elbow-like joint between the inner base appendage attached to the body and the outer scissor-like “claw.” This structure was similar to the fang joints of spiders and scorpions. Still, scientists were not completely sure if Alalcomenaeus were related to spiders and scorpions because it was hard to tell how the scissor-like head appendages were connected to the body.

With the discovery of this new well-preserved Chinese fossil, they’ve finally found some answers about Alalcomenaeus’ identity. Its large “claws” were, in fact, connected to the same body segment as the fangs of modern-day spiders and scorpions. Greg Edgecombe, of the London Natural History Museum and a co-author of the paper, said in the same press release:

We have now managed to add direct evidence from which segment the brain sends nerves into the great appendage. It’s … the same as in the fangs, for chelicerae [spiders and scorpions]. For the first time we can analyze how the segments of these fossil arthropods line up with each other the same way as we do with living species – using their nervous systems.

This new fossil’s remarkable state of preservation provided the scientists with an unprecedented opportunity to study the remaining traces of its central nervous system, even comparing it with that of modern-day spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs.

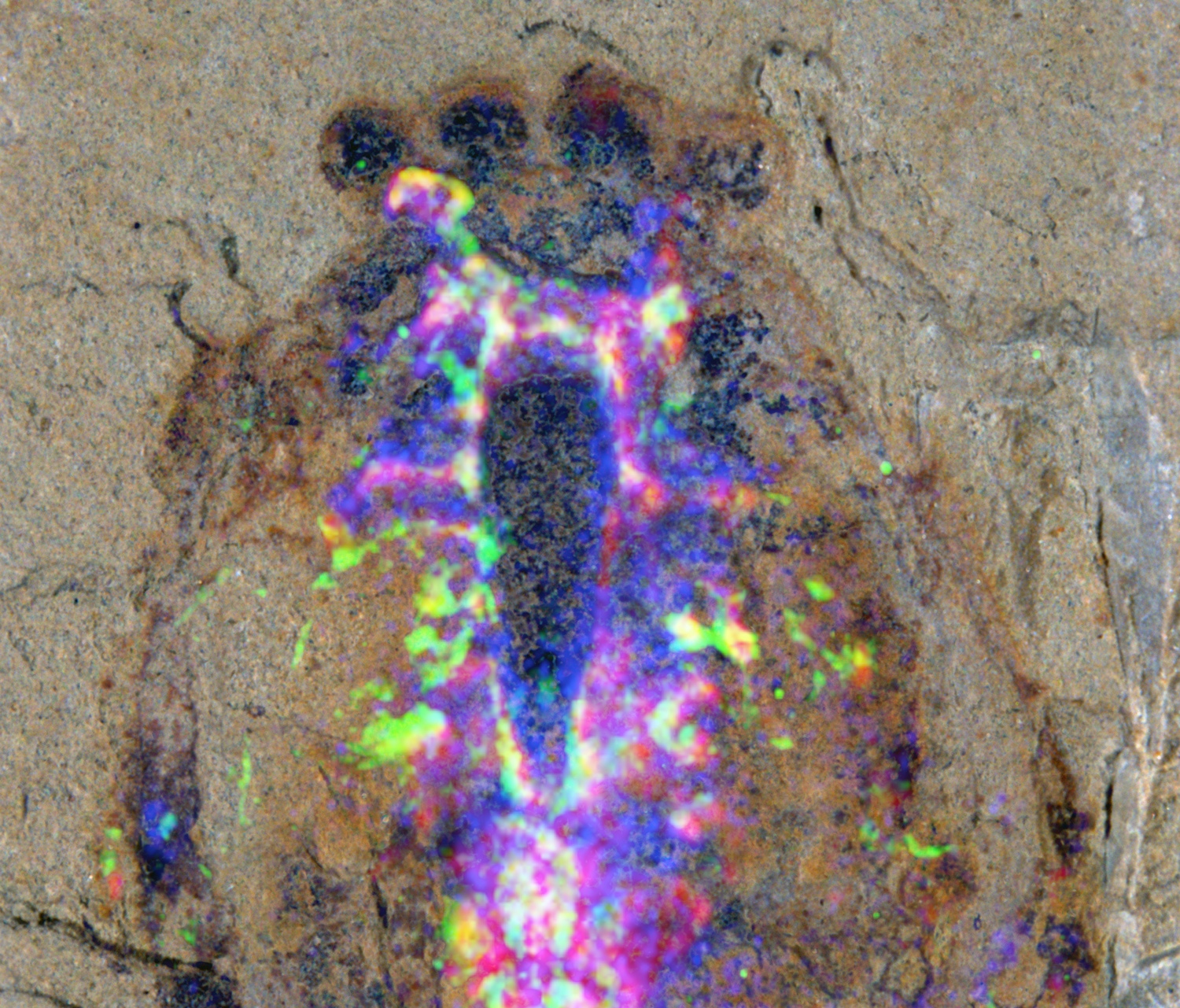

To extract an image of the fossilized nervous system, they employed several different imaging techniques. One was computed tomography (CT), that built a three-dimensional view of the nervous system features. Next, they turned to more sophisticated imaging techniques, using scanning lasers to map chemical deposits in the fossil, in particular, tracing iron deposits that occupied the space of long-gone central nervous system tissue. Images from the CT and laser imaging were processed and combined, and from it emerged an outline of a 520-million-year-old central nervous system.

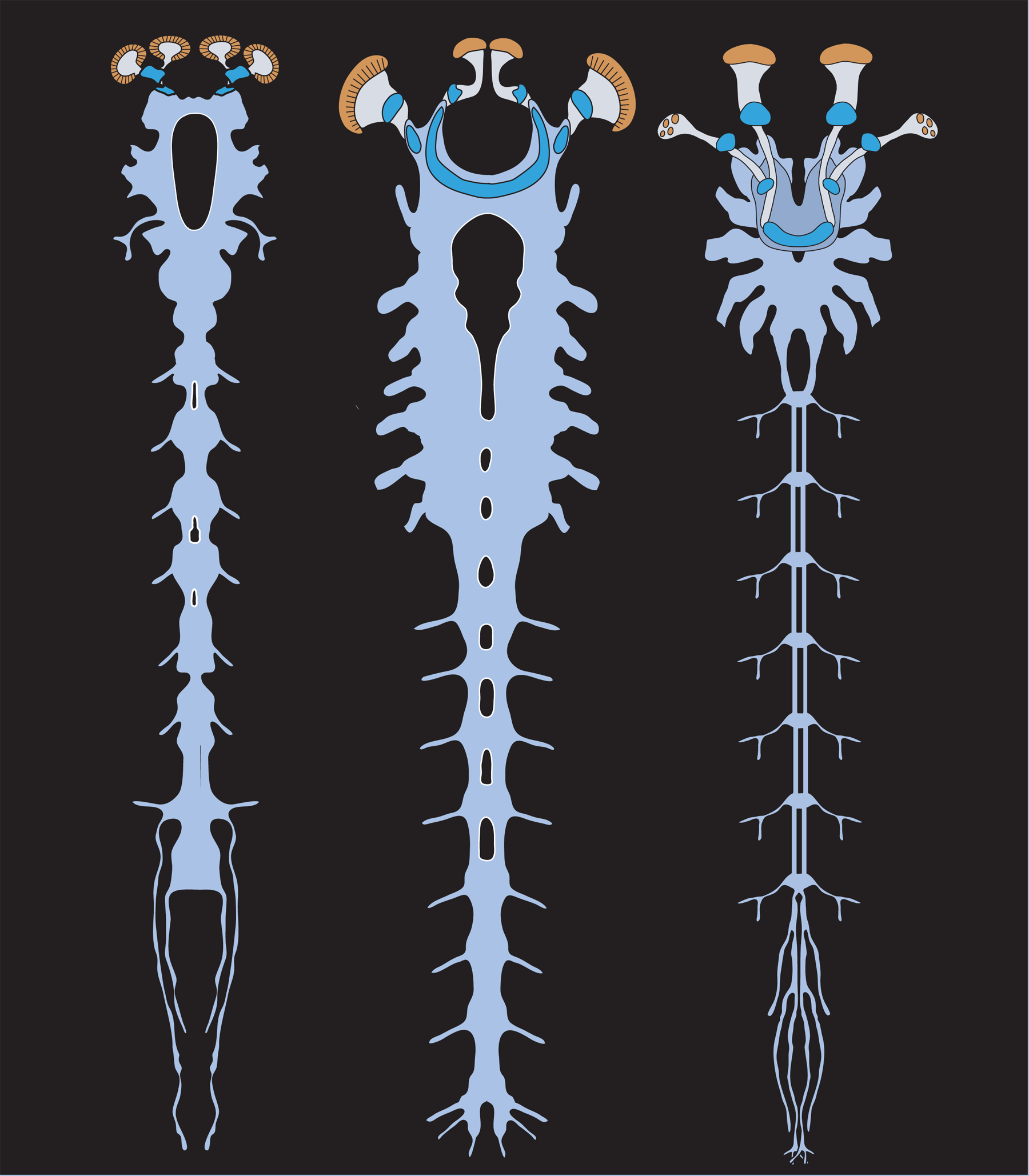

The 520-million-year-old fossil’s central nervous system had similarities with those of spiders, horseshoe crabs, and scorpions. Both have common brain structures: three clusters of nerve cells, called ganglia, were fused to form a brain, and were also integrated with ganglia in other parts of the body. Comparisons of other body features in the fossil with those of spiders, horseshoe crabs, and scorpions, also backed up their findings.

Said Strausfeld, in the same press release:

The prominent appendages that gave the megacheirans their name were clearly used for grasping and holding and probably for sensory inputs. The parts of the brain that provide the wiring for where these large appendages arise are very large in this fossil. Based on their location, we can now say that the biting mouthparts in spiders and their relatives evolved from these appendages.

Our new find is exciting because it shows that mandibulates (to which crustaceans belong) and chelicerates were already present as two distinct evolutionary trajectories 520 million years ago, which means their common ancestor must have existed much deeper in time. We expect to find fossils of animals that have persisted from more ancient times, and I’m hopeful we will one day find the ancestral type of both the mandibulate [milipedes, crustaceans, and insects] and chelicerate nervous system ground patterns. They had to come from somewhere. Now the search is on.

Bottom line: The earliest known central nervous system of an animal has been discovered in a 520-million-year-old fossilized marine creature. The immaculately-preserved fossil of this now-extinct creature showed a pair of long, forceps-like extensions from the head, and even bore traces of its central nervous system, which enabled scientists to identify it as a distant ancestor of modern-day spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs.