Since this past northern spring, when El Niño conditions in the equatorial Pacific began strengthening, scientists have been saying that this year’s El Niño will be a big one. The magnitude of the 2015 El Niño is similar to events in 1997–98 and 1982–83, say scientists, which are the two strongest events in the modern scientific record. Now, although this El Niño hasn’t yet reached its peak, scientists have observed that the ocean food web is starting to feel the loss of phytoplankton – at the base of the ocean food chain.

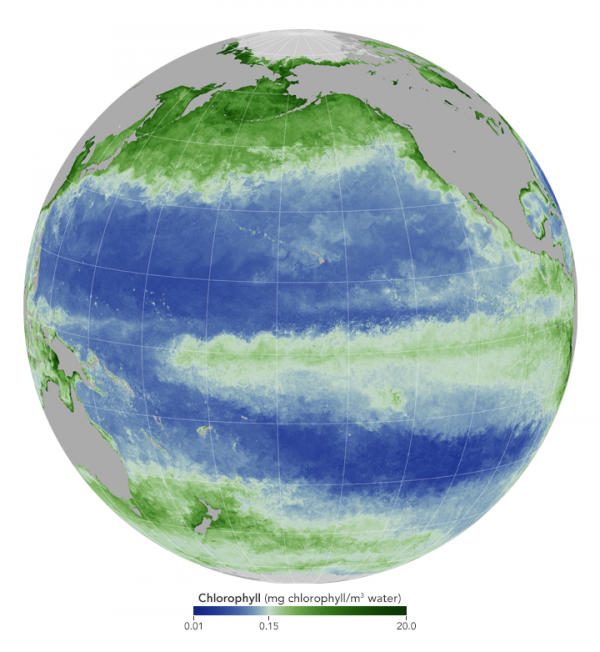

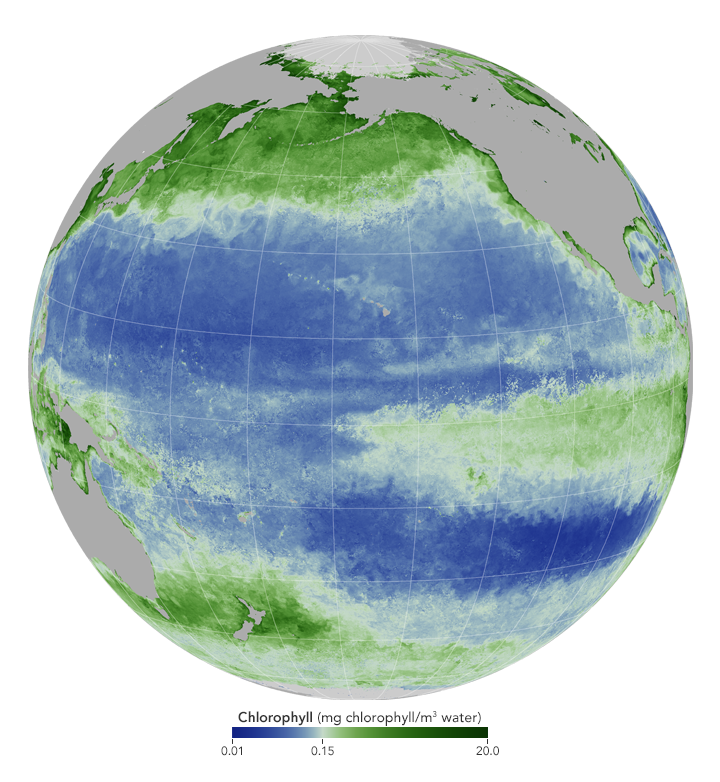

This loss – which is part of a natural cycle – is evident in declining concentrations of sea surface chlorophyll, the green pigment that indicates the presence of phytoplankton.

The globes below, derived from satellite data, compare sea surface chlorophyll in the Pacific Ocean in October 2014 and 2015. Shades of green indicate more chlorophyll and blooming phytoplankton. Shades of blue indicate less chlorophyll and less phytoplankton.

According to NASA, here’s what causes the decline of phytoplankton during an El Niño year:

Trade winds have weakened in the Eastern Pacific, disrupting the normal ocean circulation pattern and allowing the Western Pacific warm pool to propagate eastward.

Below the ocean’s surface, that warm pool is deepening the thermocline —the level that separates warmer surface waters from cooler deep ocean waters — in the east. The deeper pool of warm water has curtailed the usual upwelling of deep water nutrients to the surface of the Eastern Pacific.

With less phytoplankton available, fish that feed upon plankton, as well the bigger fish that feed on them, have a greatly reduced food supply. In past El Niños of this magnitude, the decline in fish stocks has led to famine and dramatic population declines for many marine animals — including Galapagos penguins, marine iguanas, sea lions and seals.

Part of a natural cycle. The population loss isn’t permanent. After all, the decline in ocean nutrients at the peak of an El Niño cycle is a feature of nature. The last time such a strong El Niño occurred (1997–98), there were large population declines throughout the Eastern Pacific marine food web. Then – in 1998-99 – a strong La Niña followed that had the opposite impact. The La Niña created stronger east-to-west trade winds, which increased upwelling nutrients and fertilized one of the biggest phytoplankton blooms in the satellite record.

This brought a dramatic increase in fish populations.

And so the cycle continues. Climate models predict this El Niño will peak around December and weaken during northern hemisphere spring (March–May 2016).

Enjoying EarthSky? Sign up for our free daily newsletter today!

Bottom line: Satellite data let scientists create graphics that compare phytoplankton present in October, 2015, to that present in October, 2014. Data suggest that although 2015’s strong El Niño hasn’t yet reached its peak, the ocean food web is already starting to feel the loss of phytoplankton. This loss may lead to a decline in fish stocks and dramatic population declines for many marine animals. But the declines are not permanent. If a strong strong La Niña follows, it can increase phytoplankton and lead to population surges.