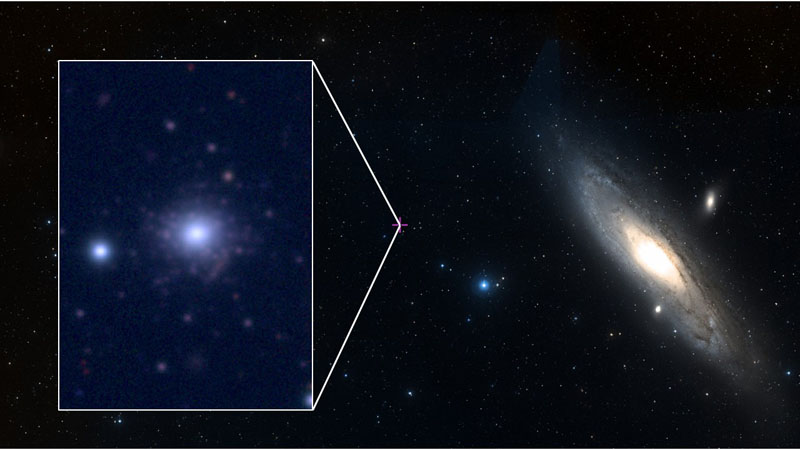

Last week (October 15, 2020), an international team of scientists published a paper in the peer-reviewed journal Science, announcing the discovery of the most metal-poor globular star cluster recorded to date. Globular star clusters are giant, symmetrical star clusters found in the halos of galaxies. And when astronomers speak of “metals,” they’re not speaking of a hard, shiny, solid material. They’re speaking of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, iron and magnesium – any and all elements born inside stars – except hydrogen and helium, which were born in the Big Bang. The newly discovered metal-poor globular cluster was hanging out in plain view in M31, aka the Andromeda galaxy, the large spiral galaxy next door to our Milky Way. The accidental discovery of this “anemic” globular cluster, as astronomers call it, has turned accepted theory about the formation of galaxies on its head. It’s also sparked questions about how and where globular clusters are formed.

EarthSky 2021 lunar calendars now available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

According to the new study, the massive globular cluster RBC EXT8 hosts stars containing 800 times fewer metals – fewer heavier elements – than can be found in our own sun. The cluster contains three times fewer metals than the previous low record for globular clusters.

RBC EXT8 was previously overlooked, or ignored, by scientists because it exhibits most of the expected characteristics of similar massive globular clusters. It weighs roughly a million times more than our sun, suggesting it is home to roughly a million stars, and – like its sibling clusters in the Andromeda galaxy’s halo – it’s assumed to have formed early in the history of the galaxy. Indeed, the stars in globular clusters are typically considered to be a galaxy’s most ancient inhabitants. Despite the traditional hallmarks, RBC EXT8’s metal-poor state is a significant departure from other globular clusters, even those already known to be metal-poor.

The find thwarts scientific theory on the formation of galaxies, leaving scientists to question what they call the metallicity floor, or lowest amount of metals believed possible in a globular cluster.

Søren Larsen, an astronomer at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, is lead author on the research. He said in a statement:

Our finding shows that massive globular clusters could form in the early universe out of gas with only a small ‘sprinkling’ of elements other than hydrogen and helium. This is surprising because such pristine gas was thought to be in building blocks too small to form such massive star clusters.

When he’s speaking of “building blocks” here, he’s speaking of protogalaxies, sometimes called “primeval galaxies,” essentially just a cloud of gas in space that’s in the process of forming a galaxy. Larsen told EarthSky that, in the immediate term, the finding of a metal-poor globular cluster in the Andromeda galaxy means that scientific theory about the formation of galaxies might need a revision or two. He said:

Large galaxies, like our Milky Way or [the Andromeda galaxy], are thought to have been built up from smaller protogalaxies. There is a relation between the masses of protogalaxies and their metallicities. That is, big galaxies contain more metals [elements heavier than hydrogen and helium]. So the most metal-poor stars and star clusters [those consisting mainly of hydrogen and helium] should have formed in the smallest protogalaxies.

To form a cluster as metal-poor as RBC EXT8 you would need a very small protogalaxy, too small to form such a massive globular cluster according to current theories for galaxy formation.

So maybe something needs to be revised or adjusted in these theories.

What scientists saw during observations at Keck Observatory in Hawaii also caused them to revisit their understanding of globular clusters. He said:

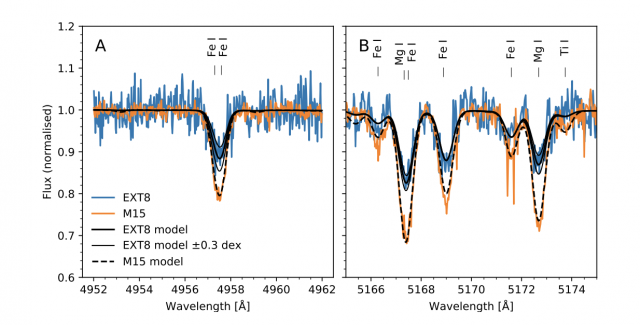

Depending on who you ask, some of the most metal-poor globular clusters in the Milky Way are Messier 15 and ESO 280-SC06, with about 200 to 300 times less metals – iron – than our sun. RBC EXT8 now pushes this limit down to about a third of what was previously thought to be the low record.

This is important because we thought we had some reasonable explanations for why globular clusters couldn’t be more metal-poor than the previous record holders. Those explanations may have to be reconsidered; we now have to try and understand how it is possible that such a metal-poor globular cluster could form.

Scientists got a third surprise when spectroscopic observations of the cluster using Keck’s High-Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) failed to exhibit the expected balance of iron and magnesium. The majority of what astronomers call the alpha-elements – silicon, calcium, titanium – present were deficient in the cluster to a factor of roughly 400, a number Larsen said could be expected based on observations of other globular clusters, but magnesium – also an alpha-element – told an entirely different story.

Magnesium is even more deficient in this cluster than iron. Stars in RBC EXT8 have about 1,600 times less magnesium than the sun. This is quite puzzling because magnesium belongs to a class of elements – the alpha elements – that are usually less deficient than iron in globular clusters. There is something strange going on with magnesium that we don’t quite understand.

According to a statement from astronomers, the strange journey that led to noticing the metal-poor globular cluster RBC EXT8 started with an unexpected hour of extra observing time on the Keck telescope in October 2019. The international team of scientists – operating remotely from University of California Santa Cruz, with Larsen on Skype from the Netherlands – was scheduled to observe globular clusters surrounding several nearby galaxies. Larsen said that what started as a short wait for celestial objects to come into view turned chance into opportunity.

At the beginning of the night, we had to wait for about an hour before our main targets would rise above the horizon. We looked for another target to fill that hour and the choice fell on this cluster, RBC EXT8 in the Andromeda galaxy. We did not suspect in advance that there would be anything special about this cluster. We simply picked it because it could be observed in the time slot we had available, and because it is one of the brightest globular clusters in the Andromeda galaxy.

Aaron Romanowsky of the University of California Observatories in Santa Cruz and San José State University is a co-author on the study. He said that finds like RBC EXT8 remind scientists to never overlook the obvious, as it might contain a science-changing surprise. He said:

I’m amazed that this remarkable star cluster was just sitting under our noses. It is one of the brightest clusters in the Andromeda galaxy and known for decades, yet no one had checked it out in detail. It shows how the universe still has many surprises for us to discover. It also reminds us to check our assumptions; in this case, it was assumed enough clusters had been investigated to know how anemic they can be.

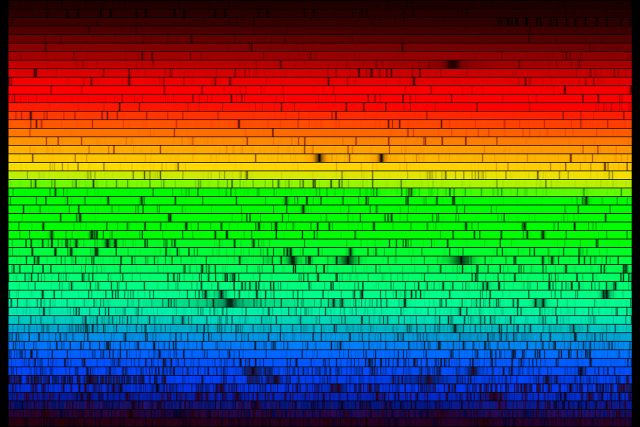

Spectra taken with the HIRES spectrometer at the Keck telescope split the makeup of RBC EXT8 into a rainbow, with absorption lines – dark regions – unveiling which elements, and how much of them, had been absorbed into the atmospheres of stars within the cluster. Larsen said:

Each atom has its own set of lines, a kind of ‘fingerprint,’ and by measuring how much light is absorbed in these lines we can work out how much iron, magnesium, etc. is present in the stars.

Despite many revelations, the study has presented more questions than answers for scientists, but Larsen and the team said they are up for the challenge. Larsen explained:

This discovery is important because it gives us a way to verify the theories of galaxy formation and things like the mass-metallicity relation. We’d also like to know if there are other clusters like RBC EXT8, so we have to try and figure out how to find them.

Bottom Line: The discovery of the most metal-poor globular cluster recorded to date has forced scientists to rethink how both galaxies and globular clusters form.

Source: An extremely metal-deficient globular cluster in the Andromeda galaxy