By Jonathan Goldenberg, Lund University

More frequent heatwaves put animals – and people – at risk

An intense heatwave that gripped Mexico in May 2024 killed more than 50 howler monkeys. Humans can escape these consequences of rising global temperatures up to a point by taking refuge in air-conditioned rooms. Other species are at the mercy of the elements and must rely on the adaptations they have inherited over millions of years of evolution to survive.

Not everyone has access to an air-conditioner, of course. Heat-related illnesses and deaths are on the rise globally. However, air-conditioning is not a desirable solution to extreme heat either. As temperatures rise, demand for fossil energy to power these cooling systems is rising too, creating a feedback loop in which hotter conditions breed higher demand for cooling and even hotter conditions.

Will we and other animals adapt quickly enough to global heating? The answer depends on how much humanity reduces greenhouse gas emissions and the capacity of all species to innovate and adapt.

Animals can regulate their body temperature through internal changes, like panting in dogs, and changes in outward behaviour. Kangaroos, for instance, lick their forearms to cool down. These examples showcase nature’s ingenuity, but it’s not certain that they will be effective against the relentless rise in global temperatures.

And so, here’s how animals are being forced to change to keep cool in a warming world.

Heatwaves force animals to alter their behavior to survive

Ecogeographical rules describe trends in how the physical traits of animals vary by geography and offer clues as to how species will adapt to a harsher climate.

Bergmann’s rule, named after the 19th-century biologist Carl Bergmann, suggests that animals in warmer climates tend to be smaller, as their larger surface area relative to the volume of their bodies helps them dissipate heat. Allen’s rule, named after zoologist Joel Allen, posits that animals in hot climates have longer appendages which make it easier for heat to escape.

Many animals are already adapting their physical traits and behavior. Some birds are developing smaller bodies and longer wings, possibly to help with heat dissipation. These adaptations may help in the short term but could alter where these birds are found. Smaller birds with longer wings can fly larger distances and so might adopt different migration patterns, with knock-on effects for the ecosystems they inhabit.

Understanding these relationships can help scientists predict and mitigate the effects of rising temperatures on biodiversity. For instance, changes in size and wing length may indicate a species struggling to cope with its current environment, alerting conservationists to create or preserve suitable habitats. This knowledge could guide the creation of wildlife corridors – natural pathways of wild habitat like forests – that allow animals to migrate to more suitable climates.

In the meantime, how different species expect to weather extreme heat depends on their metabolism and the type of environment they live in.

Climate extremes – heatwaves and deep cold – drive evolution

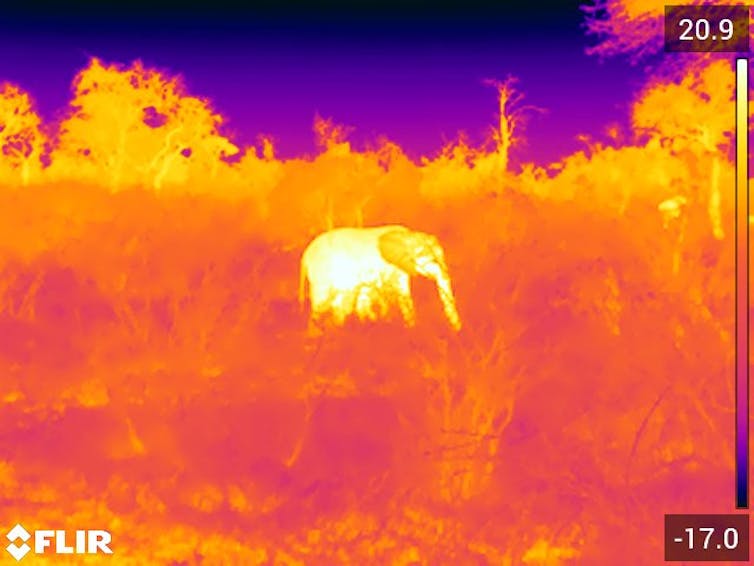

Land animals have adapted to direct sunlight and rapid swings in temperature by evolving quick-response strategies to prevent overheating. Elephants, for example, have large ears containing an extensive network of capillaries just beneath the skin which they flap, cooling their blood by fanning air over the vessels.

Water can absorb more heat before warming up than air and takes longer to cool down. This affects how heat is transferred between an animal’s body and its environment. The cod icefish, a bottom-dwelling fish found around Antarctica, thrives in frigid waters due to antifreeze proteins in its blood. Some corals opt to share their calcium carbonate skeleton with more heat-tolerant algae which can keep synthesizing sugar from sunlight in hotter water. This strategy has its limits though: another global bleaching event has demonstrated the toll of mounting heat stress.

Animals also have different strategies to manage their body heat depending on their ability to generate it. Endotherms, or warm-blooded animals, make their own heat as a byproduct of metabolism. Birds and mammals are typical endotherms. The American white pelican, a soaring water bird with a trough-like beak, rapidly vibrates its throat muscles to dissipate excess heat.

Ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals (though their blood is not actually cold), depend on their environment to regulate their body temperature. Lizards and snakes bask in the sun to warm up and take to the shade to cool down.

Evolution alone can’t protect individual animals

How far can these tried and tested methods protect species in a rapidly warming world? Polar bears could depend on their thick blubber, brown fat and dense fur to stay warm in the Arctic climate. But as temperatures rise, this insulation can become a liability and make it difficult for them to cool down. Likewise, rising heat and the destruction of shady habitats can prevent ectotherms from finding somewhere to cool down.

These pressures will take their toll on the health and habits of species. As part of a research team, I studied the behavior, body size and color features of lizards in the wild and discovered that lizards living in hotter areas of central South Africa are likely to spend less of their time active by the end of the century. That probably means less time foraging and mating, potentially stunting their growth and reproduction. Ectotherms, like amphibians and reptiles, are particularly vulnerable to rising temperatures.

Predicting how each species will respond to global heating is complex – after all, each has its own evolutionary adaptations that will bend or break as the world’s average temperature climbs. It’s clear, however, that nature’s innate resilience will not be enough on its own. Only by slashing emissions and conserving habitats can humans and wildlife thrive in harmony with the changing environment.

Bottom line: Evolution alone cannot protect animals from climate extremes like heatwaves and deep cold. Individual animals are adapting their behavior to help them survive global warming.

Jonathan Goldenberg, Postdoctoral Researcher in Evolutionary Biology, Lund University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more: Fastest carbon dioxide surge ever during year of extremes

Read more: Carbon capture is controversial, but it may be crucial

![]()