Newly-discovered fossils of a giant, extinct sea creature provide key evidence about the early evolution of arthropods – such as scorpions, spiders, lobsters, butterflies, ants, and beetles. That’s according to a study by a team of researchers from Yale and Oxford, published in Nature on March 11, 2015.

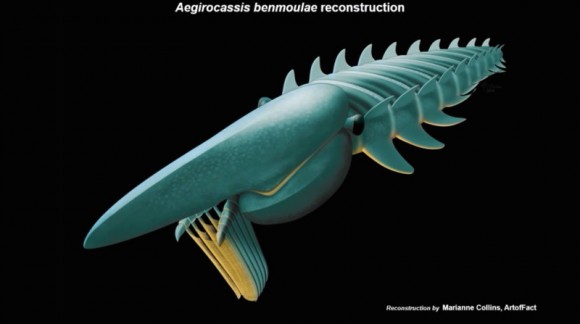

The ancient animal, named Aegirocassis benmoulae in honor of its discoverer, Mohamed Ben Moula, had modified legs, gills on its back, and a filter system for feeding. Researches say it attained a size of at least seven feet, ranking it among the biggest arthropods that ever lived. It was found in southeastern Morocco and dates back some 480 million years.

Yale University paleontologist Derek Briggs is co-author of the paper. Briggs said:

Aegirocassis is a truly remarkable looking creature. We were excited to discover that it shows features that have not been observed in older Cambrian anomalocaridids — not one but two sets of swimming flaps along the trunk, representing a stage in the evolution of the two-branched limb, characteristic of modern arthropods such as shrimps.

Since their first appearance in the fossil record 530 million years ago, arthropods have been the most species-rich and morphologically diverse animal group on Earth. They include such familiar creatures as horseshoe crabs, scorpions, spiders, lobsters, butterflies, ants, and beetles. Their success is due in large part to the way their bodies are constructed: They have a hard exoskeleton that is molted during growth, and their bodies and legs are made up of multiple segments. Each segment can be modified separately for different purposes, allowing arthropods to adapt to every environment and mode of life.

Modern arthropod legs, in their most basic form, have two branches. Each is highly modified to cater to a specific function on that leg, such as locomotion, sensing its surroundings, respiration, or copulation; or it has been lost altogether. Understanding how these double-branched limbs evolved has been a major question for scientists.

A long-extinct group of arthropods, the anomalocaridids, is considered central to the answer. The youngest known anomalocaridids are 480 million years old, and all of them looked quite alien: They had a head with a pair of grasping appendages and a circular mouth surrounded by toothed plates. Their elongate, segmented bodies carried lateral flaps that they used for swimming. Until now, it was believed that anomalocaridids had only one set of flaps per trunk segment, and that they may have lost their walking legs completely.

But the recent discovery of Aegirocassis benmoulae tells another story. The new animal shows that anomalocaridids in fact had two separate sets of flaps per segment. The upper flaps were equivalent to the upper limb branch of modern arthropods, while the lower flaps represent modified walking limbs, adapted for swimming. Furthermore, a re-examination of older anomalocaridids showed that these flaps also were present in other species, but had been overlooked. These findings show that anomalocaridids represent a stage before the fusion of the upper and lower branches into the double-branched limb of modern arthopods.

Yale scientist Peter Van Roy, who led the research, spent hundreds of hours working on the specimens. He said:

It was while cleaning the fossil that I noticed the second, dorsal set of flaps. It’s fair to say I was in shock at the discovery, and its implications. It once and for all resolves the debate on where anomalocaridids belong in the arthropod tree, and clears up one of the most problematic aspects of their anatomy.

Aegirocassis benmoulae is also remarkable from an ecological standpoint, note the researchers. While almost all other anomalocaridids were active predators that grabbed their prey with their spiny head limbs, the Moroccan fossil has head appendages that are modified into an intricate filter-feeding apparatus. This means that the animal could harvest plankton from the oceans. Van Roy said:

Giant filter-feeding sharks and whales arose at the time of a major plankton radiation, and Aegirocassis represents a much, much older example of this — apparently overarching — trend.