NASA’s solar cycle primer packs a wealth of information about the sun — along with stunning imagery — into a three-minute video. Understanding solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and flipping poles within the big picture of sunspot cycles and solar cycles makes a daunting subject easier to understand. The NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio released this video in 2011, but it’s still great. You can watch it here:

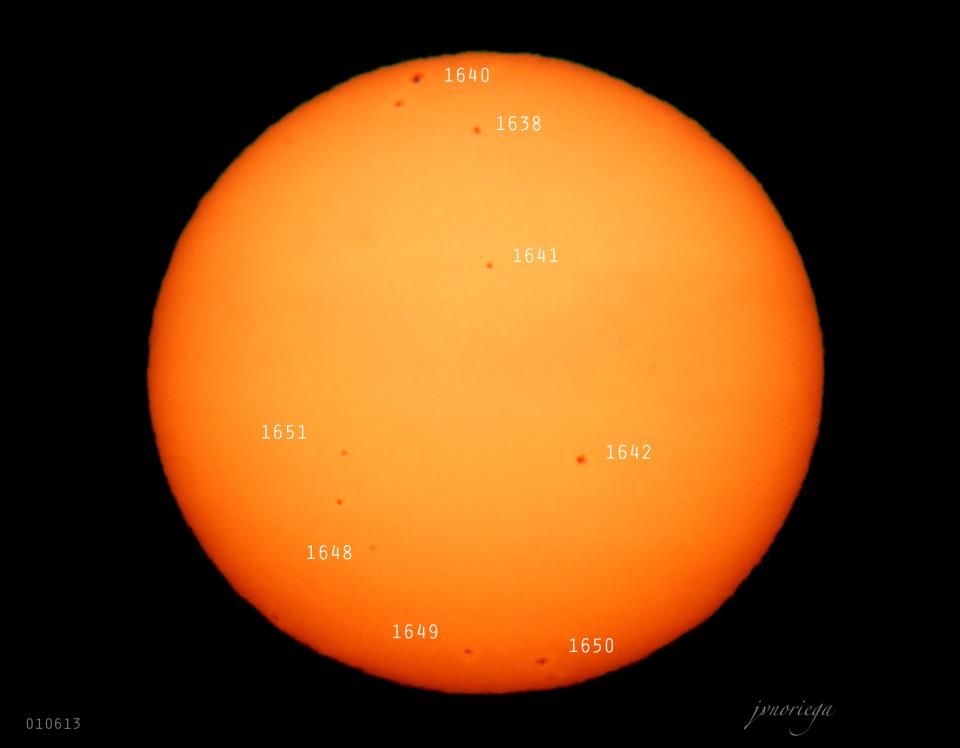

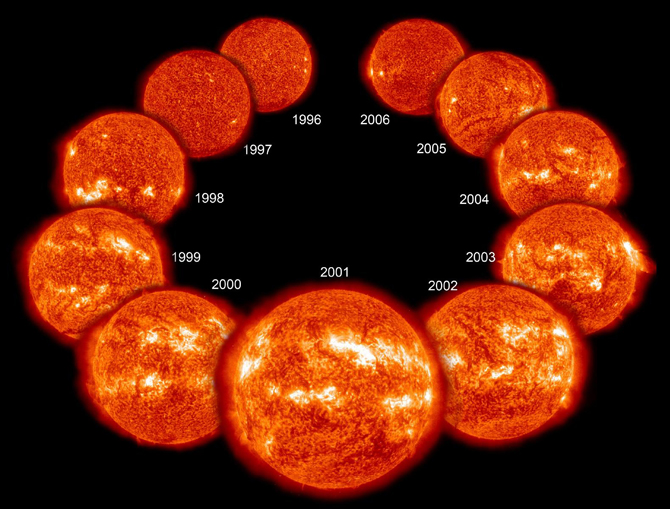

Telescopes spotted the first blemish on the sun in 1611. Later sky-watchers observed black sunspots circling around — as with the sun’s rotation. The number of sunspots was shown to increase and decrease over time in a regular cycle of approximately 11-years — called the “sunspot cycle.” The exact length of the cycle can vary — as short as eight years and as long as 14, but the number of sunspots always increases over time and then returns to low again.

More sunspots means more solar activity, when great blooms of radiation called “solar flares” or bursts of solar material called “coronal mass ejections” (CMEs) erupt from the sun’s surface. The highest number of sunspots in any given cycle is designated “solar maximum,” while the lowest number is designated “solar minimum.” Each cycle varies dramatically in intensity with some solar maxima being so low as to be almost indistinguishable from the preceding minimum.

One famous set of cycles — the Maunder Minimum — occurred from 1645 to 1715. Those who watched the sun could count enough change in sunspot number to track cycles, but the overall sunspot number dropped drastically. One thirty-year period showed only 30 sunspots, which was one thousandth of what is typically seen.

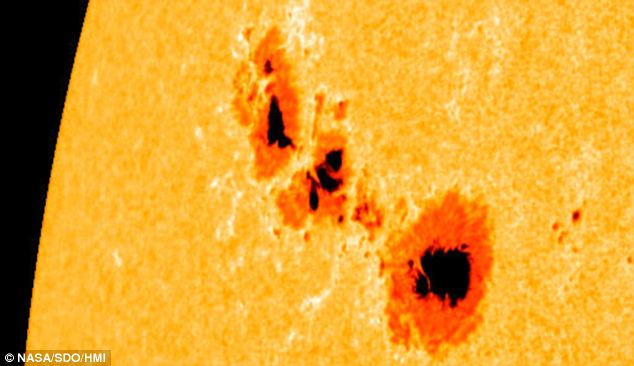

It was not until the first half of the 20th century that scientists began to understand what causes the sunspot cycle. Researchers determined that sunspots are a magnetic phenomenon and that the entire sun is magnetized with a north and a south magnetic pole — just like a bar magnet. The comparison to a simple bar magnet ends there, however, as the sun’s interior is constantly on the move.

Helioseismologists have found that magnetic material inside the sun is constantly stretching, twisting, and crossing as it bubbles up to the surface. Over time these movements eventually lead to the poles reversing.

The sunspot cycle happens because of this pole flip — north becomes south and south becomes north — approximately every 11 years. The poles reverse again back to where they started, making the full solar cycle a 22-year phenomenon. But the drama of the 11-year sunspot cycle receives the most press, as the sunspot cycle behaves the same no matter which pole is on top.

The sun is currently ramping up once again to solar maximum, so flares and CMEs are more common than they were a few years ago. This cycle may peak in late 2013 or early 2014 and should reach a minimum around 2020 — although predictions about the sun’s cycle are not ironclad. The current sunspot cycle has been the slowest of the space age (the time frame during which we have the most detailed observations).

The slower-than-expected progress of this cycle has led some researchers to speculate that the next cycle might be even smaller, with few sunspots even at solar maximum. It is still far too early to know, but even if this is the case, it has happened before and isn’t a cause for concern. Four hundred years of sunspot observations have shown that the cycle will always return.

Bottom line: NASA’s solar cycle primer, a video released October 27, 2011, explains solar flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), and flipping poles within the context of sunspot cycles and solar cycles.