Our solar system is normal

In late May 2021, astronomers released new results in a 30-year census of planetary systems beyond our own. The results show that most are arranged much like our solar system. That is, most giant exoplanets aren’t close to their parent stars, but instead live in the suburbs of their systems. That’s contrary to what astronomers thought when first discovering giant exoplanets in the 1990s. For awhile, they thought hot Jupiters – giant planets close to their stars – might be the norm. Now the California Legacy Survey, which began in the 1990s, has proven otherwise. The newly released census results describe our solar system as “normal.” Or, as astronomer Andrew Howard of Caltech said in a statement:

We’re starting to see patterns in other planetary systems that make our solar system look a bit more familiar.

The results were published on May 25, 2021, in two studies (here and here) in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal Supplement.

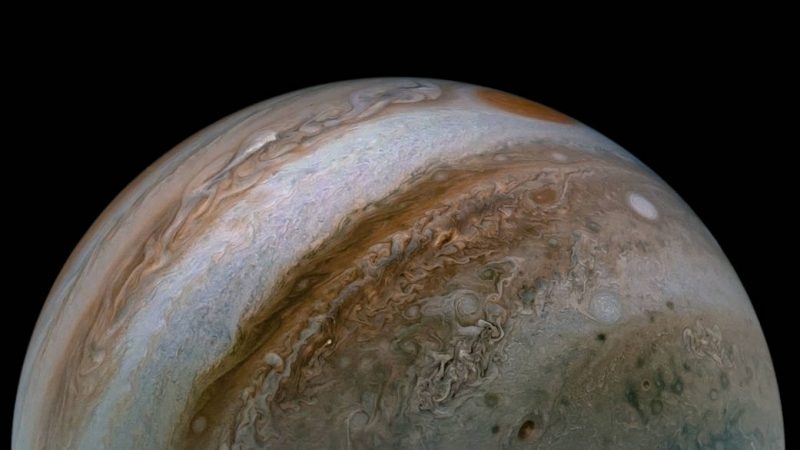

Our solar system is arranged with the rocky, terrestrial planets closest to our sun and the gas giant planets farther out. Astronomers typically speak of distances in planetary systems in astronomical units (AU). One AU is the same as Earth’s distance from the sun, or 93 million miles (150 million km). Jupiter lies 5 AU from our sun. Saturn lies 9 AU from our sun. The survey showed that giant exoplanets mostly live within 1 and 10 AU from their parent stars.

Giant planets are VIPs

Giant planets have a big impact on the formation of their planetary systems. Astronomer Lauren Weiss of the University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy commented:

Dynamically speaking, Jupiter and Saturn are the VIPs – Very Important Planets – of the solar system. They are thought to have shaped the assembly of the terrestrial planets, potentially stunting the growth of Mars and slingshotting water-bearing comets toward Earth.

Astronomers didn’t begin finding planets orbiting distant stars until the 1990s. They often find the largest gas giant planets because these planets are so massive. On the other hand, the California survey was unable to include smaller gas giant planets in the range of Uranus (19 AU) and Neptune (30 AU). They were able to note that planets the size of Jupiter and Saturn were uncommon as far out as Uranus and Neptune, however. BJ Fulton of Caltech explained:

While we can’t detect smaller planets similar to Neptune and Uranus that are very distant from their stars, we can infer that the large gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn are extremely rare in the outermost regions of most exoplanetary systems.

California Legacy Survey details

The survey data reveal that for every 100 stars in our Milky Way galaxy, there are likely to be at least 14 cold giant planets. We don’t know for sure how many stars our Milky Way contains, but it’s probably between 100 and 400 billion stars. Extrapolating from the number of giant planets detected around nearby stars, astronomers believe the Milky Way galaxy teems with billions of giant planets.

The survey targeted 719 sunlike stars for more than 30 years. It analyzed 177 planets, including 14 newly discovered gas giants. The planets have masses between 1/100 and 20 times the mass of Jupiter. (For comparison, Jupiter is 318 times as massive as Earth. In fact, Jupiter’s mass is 2.5 times that of all the other planets in our solar system combined.)

The team designed the survey to be unbiased by selecting random stars. Lee Rosenthal of Caltech explained they chose the survey members:

… As if you could put your hand in a grab bag of stars and pull a random planet out.

Biased early surveys

When astronomers first began discovering exoplanets in the 1990s, they wondered if our solar system was unusual. That was because most of the first planets to be discovered were “hot Jupiters,” similar in mass to Jupiter but orbiting very close (less than 1 AU) to their parent stars. But, as it turns out, one of the primary methods used to discover exoplanets was biased in favor of finding these large and close-in planets. That planet-hunting method, called radial velocity method, watches for a wobble in a star’s motion produced by the tug of a planet. And, of course, nearby giant planets tugged the hardest. Rosenthal said:

The hot Jupiters were easy pickings back then, but those early surveys were biased and didn’t get the full picture.

The span of 30-some years since then has improved planet-hunting technologies. Now astronomers can detect a star’s wobble from a planet orbiting far from it. And so the long-term California Legacy Survey has produced a wide range of results. As Fulton said:

The idea is to survey planets of all sizes and temperatures and then to look for patterns in the data.

Waiting for the Keck Planet Finder

The team is looking forward to new instruments that will help them see more and learn more about distant exoplanets. One instrument is the Keck Planet Finder, which may be ready as soon as 2022. The Keck Planet Finder’s main goal will be to measure the masses and orbital properties of small planets including Earths, super-Earths, and sub-Neptunes. The Planet Finder’s principal investigator is Andrew Howard of Caltech. He said:

This survey is a great jumping-off point for future instruments that are sensitive to planets the size of Earth.

Bottom line: Astronomers released the results of a 30-plus-year survey of exoplanets that found that giant planets live at a similar distance from their host star as we see here in our own solar system.

Source: The California Legacy Survey II. Occurrence of Giant Planets Beyond the Ice line