Originally published at Guy Ottewell’s blog. Reprinted here with permission.

Animals such as frogs, geckos, moths and tiny sweat bees can see color and shapes in light levels so low that we see merely faint grayness, if anything at all.

It had been assumed that such animals had vision much like ours and that their ability to find their way accurately at night was owed to cues from scent and sound. But in 2002, experiments at Lund University in Sweden showed that hawkmoths in darkness with a faint yellow source in one direction and faint blue in the opposite direction made for the color they had been trained to associate with a sugary reward; and since then scientists have found similar ability in other animals.

The trick, for insects at least, is that behind their eyes’ photoreceptors there is a layer of cells (lamina monopolar neurons) that pass the signal on to the brain, and each of these cells receives signals not from just one photoreceptor but “pools” those from several, thus amplifying them to get a brighter message for the brain.

When dung beetles (that is, some of the several thousand species of dung beetles) crowd around a turd, each grabs a piece and hurries off in a straight line, because that is quickest for getting away from others who might rob him of his prize. And to be able to do this they have to be able to see the stars. In a starless room they rush erratically, sometimes in circles.

Their main, though not only, clue is the Milky Way. If there is an artificial Milky Way overhead, they can orient, but if it is a featureless band of light they act uncertainly between two opposite possible directions. But if one end of the arch of light is brighter, as with the real Milky Way, they don’t hesitate.

The article from which I get all this is “Night Visions,” in Scientific American, May 1, 2019. It’s by Amber Dance, and if her name isn’t a pseudonym it belongs to a class of names that needs a term – names coincidentally mistakable for appropriate or seeable as appropriate, metapseudonyms, quasi pseudonyms? The article is of course instructive on the biology but a little light-starved on the astronomy. Amber wrote:

Seen from our planet, the galaxy’s thick band of stars is a fairly symmetrical line. From the beetles’ perspective, the line would look just the same when they are moving forward or backward. Yet the insects do not get turned around. Foster suspected that the beetles kept track of subtle differences in light intensity between one end of the Milky Way and the other. When he analyzed photographs of the galaxy taken from the beetles’ South African habitat, he found that the intensity of light from the northern and southern ends of the Milky Way indeed differed by at least 13 percent and some times much more, depending on how he processed the images. To test this effect on the beetles themselves, Foster built a simplified, artificial Milky Way out of single-file LED lights on an arch over an arena. He could vary the intensity of light on each side. The beetles could go straight if he gave them a 13 percent contrast between one end of the bright line and the other but wavered if the contrast dropped below that. This result indicated the animals should be able to tell the two ends of the real Milky Way.

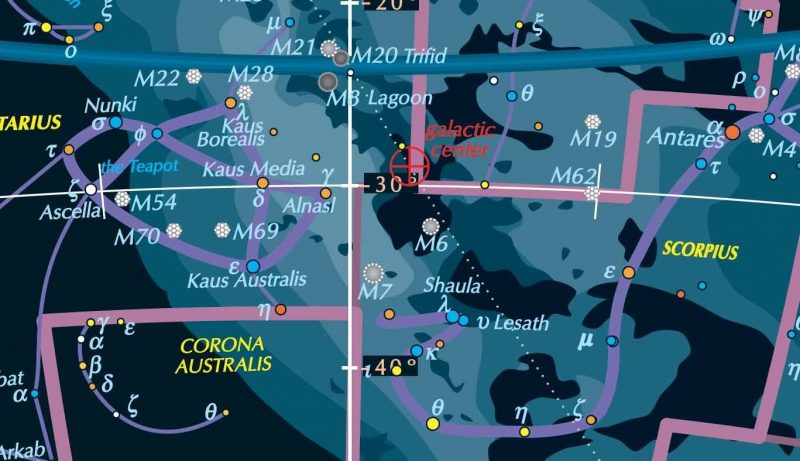

The Milky Way is quite irregular, and its center is much wider and brighter than the northern part, as you know and can see clearly in our new Map of the Starry Sky, and as these beetles know, who live in South Africa around latitude 29 degrees south where the center passes overhead.

The attitude of the Milky Way changes hourly and there is only one time of the day or night when it is an exactly overhead arch. At times, the Milky Way is almost flat to the horizon. The beetles must be adapted to that also.

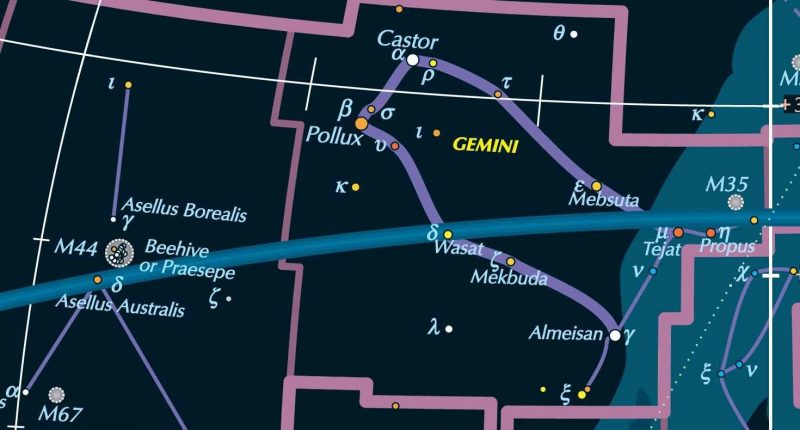

Reject any joker’s conjecture that beetles are guided by a giant ruddy ball called Beetle-Juice (Betelgeuse, shown on the map at the top of this post) that lies just west of the Milky Way.

Bottom line: Republished blog post by astronomer Guy Ottewell, about insect vision and the fact that beetles steer by the Milky Way.