Mark Lemmon, an atmospheric science professor at Texas A&M and a veteran of previous projects involving Mars, will be one of Curiosity’s camera operators and will serve as environmental science theme lead in the early days of the mission.

It should land on Mars about 12:15 a.m. Monday morning and will begin acquiring photos even before it lands, Lemmon says.

“It is scheduled to take images on its descent toward and inside Gale Crater,” Lemmon explains.

“The last seven minutes of the journey to Mars are the most critical, but hours after it lands, it should start relaying images and other science data back to NASA and the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena (California).”

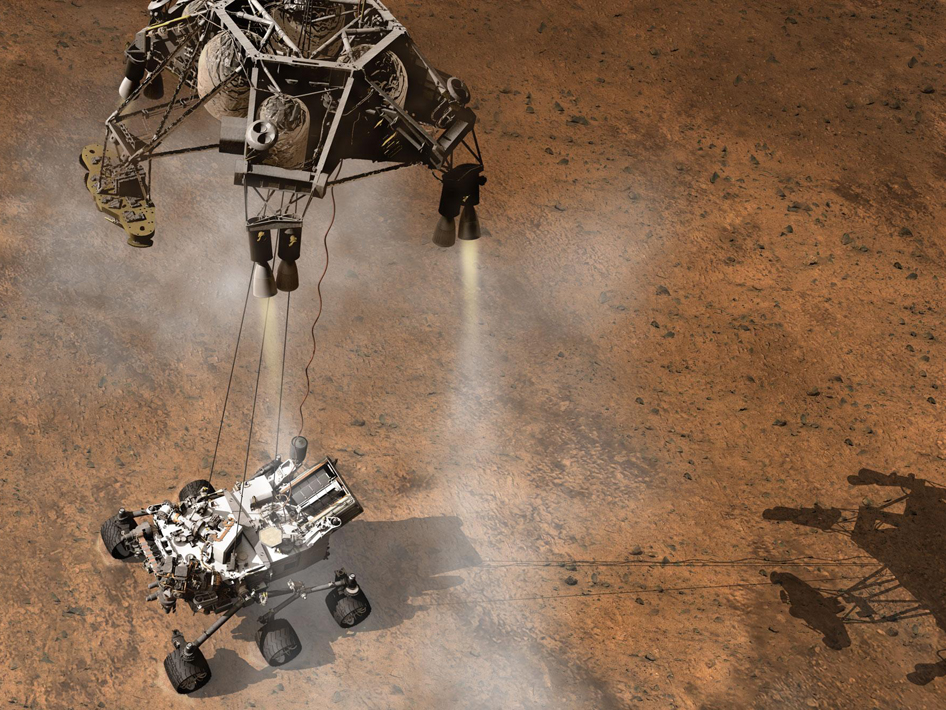

Curiosity, launched Nov. 26, 2011, has been traveling at about 13,000 miles per hour and after a series of intricate maneuvers, will come to almost a complete stop at the end of that risky seven-minute window.

Lemmon is no stranger to NASA missions. He’s participated in numerous explorations in the past, including the Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers that landed eight years ago, Phoenix, Cassini/Huygens and others.

The Curiosity mission has been years in the planning stages.

Curiosity will land in Gale Crater near the Martian equator, and over the next two years, it will investigate how climate change over billions of years has affected Mars, and examine the nearby clay layers from an environmental aspect.

It will also try to determine if Mars has ever had conditions favorable for life, even in the smallest microbial forms.

One new twist on this mission: Curiosity will have four mounted high-definition cameras that will be able to provide spectacular images never-before-seen, Lemmon notes.

“We should be able to see things we’ve never viewed before, and that’s the really exciting part,” Lemmon confirms, adding that it takes about 15 minutes for an image to relay back to Earth.

“We have taken hundreds of thousands of images on previous missions, and Curiosity’s cameras should take at least that many over the next two years. It should give us some critical answers.

“We know water was once there, and likely in large amounts. So if it is dry now, what happened? What changes occurred in Mars’ climate history that made it go from wet to dry over time? We hope to find out these answers and many more.”

Lemmon says Gale Crater was selected as the landing site for several reasons.

“It contains a large mound that is almost three miles high, but it is made of sedimentary rock,” he notes, adding that data from orbiting satellites shows near-certain proof that water was in the area at one time.

“The canyons running into Aeolus Mons – Gale Crater’s central mound – show as much of Mars’ stratigraphic history as the Grand Canyon shows here on Earth.”

Republished with permission from Texas A&M.